Arabian Sands (33 page)

Authors: Wilfred Thesiger

It was midday by now and there was still a crowd of people on the well, which had run dry. We therefore decided to stop to fill our water-skins during the night, and to water our camels at dawn before the Arabs arrived. We could camp in a little gully out of sight. Manwakh was one of the only two wells which were regarded as having permanent water in the Saar country, an area larger than Yorkshire. Yet now it had run dry after watering a couple of hundred camels, even though there had been a good rain six months earlier in the year. I wondered how the Saar managed for water in the summer and in years of drought.

In the evening Ali came to our camping place with the two men who had agreed to go with us to the Hassi. They were called Salih and Saar and were about the same age as Muhammad. Salih had a large wart on his right eyebrow, wore his hair in plaits, and was dressed in a white shirt with long, pointed sleeves; whereas Saar, the smaller of the two, wore his hair short and was dressed in a worn-out shirt, patched with so many different colours that it looked like a dervish

jibba.

They told us that they had been to the Hassi

from Najran the year before and were certain that they would be able to find this well as soon as we reached the Aradh, a limestone escarpment running down into the sands from Sulaiyil; they said it would be impossible for us to miss. In the evening they went back to their tents, but assured us that they would be with us at dawn.

After we had fed, the others took the water-skins over to the well to fill them ready for the morning start. Ordinarily I would have helped them, but now I was drained of energy, so I just lay beside the loads on the cold yielding sand and stared up at the stars. Later bin Kabina came and sat beside me. He did not speak and I was glad to have him there.

Sadr had told us that Ibn Saud had a post at the Hassi, and it therefore seemed unlikely that we should be able to water there and slip away again unobserved. I wondered what the King would say when he heard that I had crossed the desert without his permission, and whether he would identify me as the Englishman to whom he had refused permission to do the journey two years before. I only hoped that if we succeeded his anger would be tempered by some admiration for our achievement.

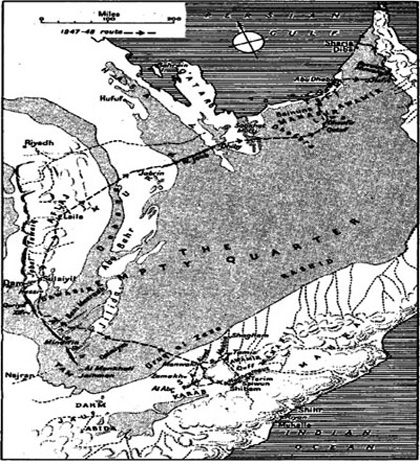

The crossing of the Western Sands

to the Hassi well and Sulaiyil ends

in arrest and imprisonment.

It was a bleak morning with a cold wind blowing from the north-east. The sun rose in a dusty sky but gave no warmth. Bin Kabina set out dates and fragments of bread, left over from the previous night, before calling to us to come and eat. I refused, having no desire for food, and remained where I was, crouching behind a rock, trying to find shelter from the cutting wind and eddies of driven sand. I had slept little the night before, trying to assess the dangers and difficulties which lay ahead. Later, in grey borderlands of sleep, I had struggled knee-deep in shifting sand with nightmares of disaster. Now, in the cold dawn, I questioned my right to take these men who trusted me to what the Saar vowed was certain death. They were already moving about their tasks preparatory to setting off, and only an order from me would stop them. But I was drifting forward, slack-willed, upon a movement which I had started, half-hoping that Salih and Sadr would fail to come and that then we could not start.

Some Saar were already at the well, which would soon be surrounded by Arabs impatient to water their animals. We drove ours down there and filled the troughs, but they would only sniff at the ice-cold water instead of drinking, and drink they must if they were to survive for sixteen waterless days, struggling heavily-loaded through the sands. Bin Kabina and I went back to sort the loads, while the others couched each roaring camel in turn, and, after tying her knees to prevent her from getting up, battled to hold her weaving neck, so that they could pour down her throat the water she did not want. Bin Kabina set aside the rice and the extra flour to give to Ali. We were taking with us two hundred pounds of flour, which was as much as we could carry, a forty-pound package of

dates, ten pounds of dried shark-meat, and butter, sugar, tea, coffee, salt, dried onions, and some spices. There were also two thousand Maria Theresa dollars, which weighed very heavily, three hundred rounds of spare ammunition, my small box of medicines, and about fifty gallons of water in fourteen small skins. I knew already that several of these skins sweated badly, but had not been able to get others from the Saar. Even so, I reckoned that if we rationed ourselves to a quart each for every day and to a quart for cooking and coffee, we should be all right, even if we lost half our water from evaporation and leakage. This water was sweet, very different from the filthy stuff we had carried with us the year before. While we were busy dividing our stores into loads of suitable weight, Salih and Sadr arrived and I was glad to see that both their camels were powerful animals in good condition. We had decided the night before that we would load the spare camels heavily, at the risk of foundering them before we reached the Hassi, so as to save our mounts. I hoped that the two Saar would be able to slip away unobserved from that well, even if the rest of us were detained, and-it was therefore important that their camels should be spared as much as possible. They must carry only the lightest loads, if they carried anything at all. I gave them the rifles which I had promised, and fifty rounds of ammunition each. Their friends who had come with them examined these weapons critically, but could find nothing wrong. I had already presented Muhammad and Amair each with a rifle and a hundred rounds of ammunition. Bin Ghabaisha had the rifle I had given him in Saiwun, bin Kabina the one I had given him the year before, and I had my sporting .303, so we were a well-armed party.

The others returned from the well and we loaded the camels. The sun was warmer now and I felt more cheerful, reassured by the good spirits of my companions, who laughed and joked as they worked. Before leaving, we climbed the rocky hill near the well, and Sadr’s uncle, a scrawny old man in a loincloth, showed us once more the direction to follow, pointing with both his arms. With his wild hair, gaunt face, and outstretched arms he looked, I thought, like a prophet predicting doom. I was almost surprised when he said in an ordinary

voice that we could not go wrong, as we should have the Aradh escarpment on our left when we reached the Jilida. Standing behind him I took a bearing with my compass. As we climbed down the hill Ali told me that there had been another fight between the Yam and the Karab near al Abr two days before, and that the bin Maaruf had now decided to abandon Manwakh and to move tomorrow to the Makhia. He said that this was why there were already so many Arabs filling their skins at the well.

We were leaving only just in time. The camels lurched to their feet as we took hold of the head-ropes, and, after each of the Rashid had tied a spare camel behind his own, we moved off on foot. The Saar on the well stopped work to watch us go and I wondered what they were saying. Ali came with us a short distance, and then, after embracing each of us in turn, went back. We had started on our journey, and holding out our hands we said together, ‘I commit myself to God.’

Two hours later Sadr pointed to the tracks of five camels that had been ridden ahead of us the day before. At first we wondered if they were Yam, but after some discussion Sadr and Salih were convinced that they were Karab and therefore friendly Muhammad asked me to judge which was the best camel. I pointed at random to a set of tracks and they all laughed and said I had picked out the one which was indubitably the worst. They then started to argue which really was the best. Although they had not seen these camels they could visualize them perfectly. Amair, bin Ghabaisha, and Sadr favoured one camel, Muhammad, bin Kabina, and Salih another. I knew nothing about Sadr and Salih’s qualifications, but felt sure that Amair and bin Ghabaisha were right since they were better judges of a camel than Muhammad or bin Kabina. Not all Bedu can guide or track, and Muhammad was surprisingly bad at both. He was widely respected as the son of bin Kalut and was inclined to be self-important in consequence, but really he was the least efficient of my Rashid companions. Bin Ghabaisha was probably the most competent, and the others tended to rely on his judgement, as I did myself. He was certainly the best rider and the best shot, and always graceful in everything he did. He had a quick smile and

a gentle manner, but I already suspected that he could be both reckless and ruthless, and I was not surprised when within two years he had become one of the most daring outlaws on the Trucial Coast with a half a dozen blood-feuds on his hands. Amair was equally ruthless, but he had none of bin Ghabaisha’s charm. He had a thin mouth, hard unsmiling eyes, and a calculating spirit without warmth. I did not like him, but knew that he was competent and reliable. Travelling alone among these Bedu I was completely at their mercy. They could at any times have murdered me, dumped my body in a sand-drift, and gone off with my possessions. Yet so absolute was my faith in them that the thought that they might betray me never crossed my mind.

We travelled through low limestone hills until nearly sunset, and camped in a cleft on their northern side. The Rashid did not trust the Saar whom we had left at Manwakh, so Amair went back along our tracks to keep watch until it was dark, while bin Ghabaisha lay hidden on the cliff above us watching the plain to the north, which was a highway for raiders going east or west. We started again at dawn, after an uneasy watchful night, and soon after sunrise came upon a broad, beaten track, where Murzuk and the Abida had passed two days before.

Bin Kabina and Amair stayed behind to try to identify some of the looted stock by reading the confusion in the sand. We had gone on a couple of miles when they caught up with us, laughing as they chased each other across the plain. They appeared to be in the best of spirits, and I was surprised when bin Kabina told me that he had recognized the tracks of two of his six camels among the spoil. He had left these two animals with his uncle on the steppes. Luckily, Qamaiqam, the splendid camel on which he had crossed the Empty Quarter the year before, and the other three were with his brother at Habarut. He told us which animals they had been able to identify, but said that there had been so many animals that it was only possible to pick out a few that had travelled on the outskirts of the herd. As I listened I thought once again how precarious was the existence of the Bedu. Their way of life naturally made them fatalists; so much was

beyond their control. It was impossible for them to provide for a morrow when everything depended on a chance fall of rain or when raiders, sickness, or any one of a hundred chance happenings might at any time leave them destitute, or end their lives. They did what they could, and no people were more self-reliant, but if things went wrong they accepted their fate without bitterness, and with dignity as the will of God.

We rode across gravel steppes which merged imperceptibly into the sands of the Uruq al Zaza. By midday the north-east wind was blowing in tearing gusts, bitter cold but welcome, as it would wipe out our tracks and secure us from pursuit. We pressed on until night, hoping in vain to find grazing, and then groped about in the dark feeling for firewood. Here it was dangerous to light a fire after dark, but we were too cold and hungry to be cautious. We found a small hollow, lit a fire, and sat gratefully round the flames. At dawn we ate some dates, drank a few drops of coffee, and started off as the sun rose.

It was another cold grey day, but there was no wind. We went on foot for the first hour or two, and then each of us, as he felt inclined, pulled down his camel’s head, put a foot on her neck, and was lifted up to within easy reach of the saddle. Muhammad was usually the first to mount and I the last, for the longer I walked the shorter time I should have to ride. The others varied their positions, riding astride or kneeling in the saddle, but I could only ride astride, and as the hours crawled by the saddle edge bit deeper into my thighs.

For the next two days we crossed hard, flat, drab-coloured sands, without grazing, and, consequently, had no reason to stop until evening. On the second day, just after we had unloaded, we saw a bull oryx walking straight towards us. To him we were in the eye of the setting sun and he probably mistook us for others of his kind. As only about three Englishmen have shot an Arabian oryx, I whispered to bin Ghabaisha to let me shoot, while the oryx came steadily on. Now he was only a quarter of a mile away, now three hundred yards, and still he came on. The size of a small donkey – I could see his long straight horns, two feet or more in length, his pure white body, and the dark markings on his legs and face. He stopped

suspiciously less than two hundred yards away. Bin Kabina whispered to me to shoot. Slowly I pressed the trigger. The oryx spun round and galloped off. Muhammad muttered disgustedly, ‘A clean miss,’ and bin Kabina said loudly, ‘If you had let bin Ghabaisha shoot we should have had meat for supper’; all I could say was ‘Damn and blast!’