Arabian Sands (6 page)

Authors: Wilfred Thesiger

I was restless. For three years I had been planning this journey, and now it was over and the future seemed empty. I dreaded a return to civilization, where life promised to be very dreary after the excitements of the last eight months. At Jibuti I played with the idea of buying de Monfried’s dhow. I had read his

Aventures de Mer

and

Secrets de la Mer Rouge

and had talked to the Danakil who had sailed with him. I was fascinated by his accounts of a free and lawless life.

I returned, however, to England, joined the Sudan Political Service, and went to Khartoum at the beginning of 1935. I was twenty-four. I had spent nearly half my life in Africa, but it was an Africa very different from this. Khartoum seemed like the suburbs of North Oxford dumped down in the middle of the Sudan. I hated the calling and the cards, I resented the trim villas, the tarmac roads, the meticulously aligned streets in Omdurman, the signposts, and the public conveniences. I

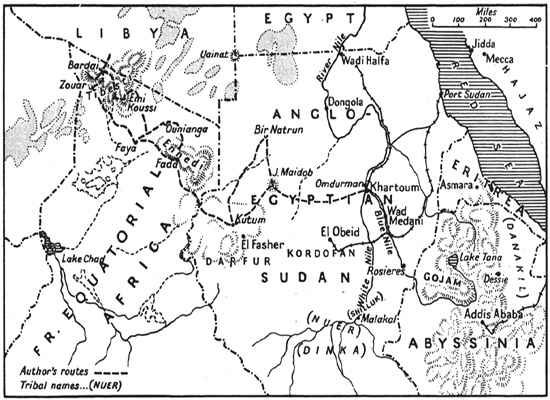

longed for the chaos, the smells, the untidiness, and the haphazard life of the market-place in Addis Ababa; I wanted colour and savagery, hardship and adventure. Had I been posted to one of the towns I have no doubt that, disgruntled, I should have left the Sudan within a few months, but Charles Dupuis, Governor of Darfur, had anticipated my reaction and had asked that I should be sent to his Province. I was posted to Kutum in northern Darfur, where I served under Guy Moore, a man of great humanity and understanding. He had come to the Sudan from the deserts of Iraq, where he had been a Political Officer at the end of the First World War. He loved talking of those days among the Arabs, and his reminiscences made a great impression on me. We were the only Englishmen in the District, which was the largest in the Sudan and covered more than 50,000 square miles. It was desert country with a small but very varied population of about 180,000. There were nomadic Arab tribes, others of Berber origin, Negro cultivators in the hills, and in the south some of the Bagara, the cattle-owning Arabs, who had won fame as the bravest fighting men in the dervish army.

I spent most of my time on trek travelling with camels. In the Danakil country I had used camels for carrying loads; here for the first time I rode them. District Commissioners usually travelled with a baggage train of four or five camels loaded with tents, camp furniture, and tinned foods. Guy Moore taught me to travel light and eat the local food. I usually travelled accompanied by three or four of the local tribesmen; I kept no servants who were not from the district. Where there were villages, the villagers fed us, otherwise we cooked a simple meal of porridge and ate together from a common dish. I slept in the open on the ground beside them and learnt to treat them as companions and not as servants. Before I left Kutum I had some of the finest riding camels in the Sudan, for I bought the best that I could find; they interested me far more than the two horses I had in my stable. On one of the camels I rode 115 miles in twenty-three hours, and a few months later I rode from Jabal Maidob to Omdurman, a distance of 450 miles, in nine days.

During my first winter in the Sudan I travelled for a month

in the Libyan desert. I planned to visit the wells of Bir Natrun, one of the few places in this desert where there was water. It was not in Kutum district, not even in the same province, but as no officials ever went there, and as I had been told I should be refused if I did ask permission from Khartoum, I decided to visit it and say nothing. I started from Jabal Maidob with five companions. As we topped a rise on our first day and saw the stark emptiness before us I caught my breath. There were eight waterless days ahead of us to Bir Natrun and twelve more by the way we planned to return. For the first two days we saw occasional white oryx and a few ostriches; after that there was nothing. Hour after hour, day after day, we moved forward and nothing changed; the desert met the empty sky always the same distance ahead of us. Time and space were one. Round us was a silence in which only the winds played, and a cleanness which was infinitely remote from the world of men.

On my return I went into Fasher – the Provincial Headquarters – for Christmas. At dinner there was talk of the Italians having occupied Bir Natrun. Recently they had seized the small oasis of Uainat on the Sudan-Libyan frontier which had been assumed to belong to the Sudan. This incident had led to protests and the exchange of notes. Now I heard that Dongala had reported to Khartoum that some Arabs had recently seen white men at Bir Natrun, and that this was assumed to be further aggression by the Italians. ‘Emergency measures’ had been taken and aircraft had been moved to Wadi Haifa. I interrupted to say that I could not believe this since I had just returned from Bir Natrun, where I had only seen a few Arabs. A stunned silence followed, and then the CO. of the Western Arab Corps said grimly, ‘I suppose

you

are the Italians.’ A little later, when I went through Khartoum on leave, it was pointed out to me firmly but sympathetically by the Civil Secretary that it was not customary to travel in someone else’s district without the D.C.’s consent, and certainly not to tour in another province without the Governor’s permission.

At the end of 1937 I heard that I was to be transferred to

Wad Medani, the headquarters of the Blue Nile Province and the centre of the Gezira Cotton Scheme. I was appalled at the idea of spending two years or more in this African suburbia. On my way through Khartoum on leave I persuaded the Civil Secretary to let me resign from the permanent Political Service and rejoin as a contract D.C. on the understanding that I should not be asked to serve except in the wilds. This meant that I should no longer be eligible for a pension, but I doubted that I really wished to spend the rest of my active life in the Sudan. I had been happy in Darfur. I had found satisfaction in the stimulating harshness of this empty land, pleasure in the nomadic life which I had led. I had loved the hunting. It had been exciting to stalk barbary sheep among the craters of Maidob, or kudu in the Tagabo hills, or addax or oryx on the edge of the Libyan desert. It had been wildly exciting to charge with a mob of mounted tribesmen through thick bush after a galloping lion, to ride close behind it when it tired, while the Arabs waved their spears and shouted defiance, to circle round the patch of jungle in which it had come to bay, trying to make out its shape among the shadows, while the air quivered with its growls. I had grown fond of the people among whom I lived. I valued the qualities which they possessed and was jealous for the preservation of their way of life. But I knew that I was not really suited to be a D.C. as I had no faith in the changes which we were bringing about. I craved for the past, resented the present, and dreaded the future.

I was posted to the Western Nuer District of the Upper Nile Province. I went there on my return from leave, part of which I had spent in Morocco.

The Nuer are Nilotics, kin to the Dinka and Shilluk, and they live in the swamps or Sudd which borders the White Nile to the south of Malakal. A pastoral people who own great herds of cattle, they are a virile race of tall, stark-naked savages with handsome arrogant faces and long hair dyed golden with cow’s urine. The District had only been administered since 1925, and there had been some fierce fighting before they had submitted, but they were a people who had exerted a fascination over nearly all Englishmen who had encountered them.

I lived on a paddle-steamer with Wedderburn Maxwell, my District Commissioner. We were left to ourselves; all that the Governor asked was that he should get an occasional letter to say that we were all right. We kept a few files for our own convenience, but were not bothered with the mass of paper which accumulated on office desks in more conventional districts. We were happily out of touch with the rest of the Sudan, for there were no roads anywhere in the district; it was only possible to get there by steamer and to travel in the district with porters. The country was full of game. I once saw a thousand elephants in one vast herd along the river’s banks. There were buffalo and white rhinoceros, hippopotamus, giraffe, and many kinds of antelope, and there were leopards, and a great number of lions. I shot seventy lions during the five years I was in the Sudan.

This was the Africa which I had read about as a boy and which I had despaired of finding in the Sudan when I first saw Khartoum: the long line of naked porters winding across a plain dotted with grazing antelope; my trackers slipping through the dappled bush as we followed a herd of buffalo; the tense excitement as we closed in upon a lion at bay; the grunting cough as it charged; the reeking red shambles as we cut up a fallen elephant, a blood-caked youth grinning out from between the gaping ribs; white cattle egrets flying above the Nile against a background of papyrus, such as is depicted in the Pharaohs’ tombs; Lake No and the setting sun reflected redly in water that shone like polished steel; hippopotamus grunting close by in a darkness that was alive with other sounds; smoke rising over Nuer cattle camps; the leaping, twisting forms caught up in the excitement of a war dance; the rigid figures of young men undergoing the agony of initiation. Earlier in my life this would have been all that I could have asked, but now I was troubled with memories of the desert.

In 1938 I spent my leave in the Sahara and visited the Tibesti mountains, which were unknown except to French officers who had travelled there on duty. I left Kutum early in August accompanied by a Zaghawa lad, who had been my servant since I came to the Sudan, and an elderly Badayat who knew the language of the Tibbu, having lived in Tibesti. I hired

camels in Darfur to take us as far as Fay a; after that we should need camels used to the mountains. We travelled light, the distances being great and the time short.

Among the Nuer I had lived in a tent apart from my men, waited on by servants; I had been an Englishman travelling in Africa, but now I could revert happily to the desert ways which I had learned at Kutum. For this was the real desert where differences of race and colour, of wealth and social standing, are almost meaningless; where coverings of pretence are stripped away and basic truths emerge. It was a place where men live close together. Here, to be alone was to feel at once the weight of fear, for the nakedness of this land was more terrifying than the darkest forest at dead of night. ID the pitiless light of day we were as insignificant as the beetles I watched labouring across the sand. Only in the kindly darkness could we borrow a few square feet of desert and find homeliness within the radius of the firelight, while overhead the familiar pattern of the stars screened the awful mystery of space.

We did long marches, sometimes riding for eighteen or twenty hours. At last we saw, faint like a cloud upon the desert’s edge, the dim outline of Emi Koussi, the crater summit of Tibesti. As we drew near it dominated our world, sharp blue at dawn, and black against the setting sun. We climbed it with difficulty, and stood at last upon the crater’s rim, 11,125 feet above sea-level. Beneath us in the crater’s floor was the vent, a great hole a thousand feet deep. To the north were range upon range of jagged peaks, rising from shadowed gorges, an awful scene of utter desolation. Everywhere the rocks were slowly crumbling away, eroded by sun and wind and storm. It was a sombre land, black and red and brown and grey. We travelled across wind-swept uplands, over passes and through narrow gorges, under precipices, past towering peaks. From Bardai we visited the great crater of Doon, 2,500 feet in depth. We camped in the Modra valley beneath Tieroko, the most magnificent of all the Tibesti mountains. When we returned to Darfur we had ridden over two thousand miles in three months.

In the desert I had found a freedom unattainable in civilization; a life unhampered by possessions, since everything that was not a necessity was an encumbrance. I had found, too, a comradeship inherent in the circumstances, and the belief that tranquillity was to be found there. I had learnt the satisfaction which comes from hardship and the pleasure which springs from abstinence: the contentment of a full belly; the richness of meat; the taste of clean water; the ecstasy of surrender when the craving for sleep becomes a torment; the warmth of a fire in the chill of dawn.

I went back to the Nuer, but I was lonely, sitting apart on a chair, among a crowd of naked savages. I wanted more than they could give me, even while I enjoyed being with them. The Danakil journey had unsuited me for life in our civilization; it had confirmed and strengthened a craving for the wilds. The Nuer country would have met this need, but three years in Darfur and my recent journey to Tibesti had taught me to ask for more than this, for something which I was to find later in the deserts of Arabia.

I had been posted back to Kutum, but was still on leave when the war started, and being without a district I was allowed to join the Sudan Defence Force in April 1940. For me the Abyssinian campaign had the quality of a crusade. Ten years earlier I had watched the Emperor Haile Selassie being crowned in Addis Ababa; six years after this I had seen him descend from the train at Victoria into exile. I am proud to have served in Abyssinia with Sandford’s mission which prepared the way for Haile Selassie’s restoration, and to have fought in Wingate’s Gideon Force which took him back from the Sudan through Gojam to Addis Ababa. From Abyssinia I was sent to Syria, where I served in Jabal al Druze and later worked for a year among the tribes.