Ardor (9 page)

Authors: Roberto Calasso

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Renou went even further: “It should be noted, looking deeper, that the very notion of

brahman

, as elaborated in the thought of the Upani

ṣ

ads, is also itself a product of the

brahmodya

: in the sense that it is under this form of dialectic and in this climate of dispute that the speculation on

brahman

, the nucleus of the Upani

ṣ

ads, is constituted.”

In the

B

ṛ

had

ā

ra

ṇ

yaka Upani

ṣ

ad

we find not only supreme examples of

brahmodya

, but also a first attempt by this form to slip away from itself, to leave its own shell and set off in a new direction, which—in the absence of any other term and even before the notion existed—might be described as that of the

novel.

The protagonist is still Y

ā

jñavalkya. But the tone suddenly changes. The great

brahmodya

with Janaka has ended and we reach the final section of the fourth “lesson” with these words: “At that time Y

ā

jñavalkya had two wives, Maitrey

ī

and K

ā

ty

ā

yan

ī

. Maitrey

ī

knew how to speak of

brahman

, K

ā

ty

ā

yan

ī

possessed the knowledge of women. When Y

ā

jñavalkya decided to start another kind of life, he said: ‘Maitrey

ī

, I want to leave these places to lead the life of a wandering monk: so I want an agreement to be made between K

ā

ty

ā

yan

ī

and you.’”

Here, for the first time, we are far removed from the climate of disputation and ritual. We are part of an intimate, sober, informal discussion between an elderly couple. The essence of the prose, of the prose that tells a story without any meter and without any ritual obligations, seems to be inviting us to eavesdrop on a private matter, the unique story of three people. The great brahmin Y

ā

jñavalkya takes leave of his readers through his two wives, Maitrey

ī

and K

ā

ty

ā

yan

ī

, about whom we know nothing except that one is versed in

brahman

while the other possesses the knowledge typical of women (whatever that might mean). It is a moment of great intensity, not only because it is the prelude to a discourse by Y

ā

jñavalkya that can be considered his final word on the

ā

tman

—and in particular on that “love for the Self” without which even

brahman

“abandons” us—but also because it is repeated twice in the

B

ṛ

had

ā

ra

ṇ

yaka Upani

ṣ

ad

, in similar terms (2.4.1–14; and 4.5.1–15). And it is at the end of his instruction to Maitrey

ī

that Y

ā

jñavalkya repeats his negative definition of

ā

tman

, in exactly the same terms as those he had already used with King Janaka. This time Y

ā

jñavalkya does not leave the scene to move on to other disputations and other sacrificial gatherings. This time we read: “Having spoken thus, Y

ā

jñavalkya left.” The text continues for another two

adhy

ā

yas

, without involving him further. That scene with Maitrey

ī

, those words on

ā

tman

are his last appearance before he goes off into the forest. And the detail confirming that we have entered the world of the novel is that Y

ā

jñavalkya’s final concern was to establish an “agreement” between the two wives whom he was about to leave.

III

ANIMALS

Consumed by the arrogance of knowledge, the young Bh

ṛ

gu, son of the supreme god Varu

ṇ

a, was sent off by his father into the world (into this world, according to the

Ś

atapatha Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a

, into the other world according to the version in the

Jaimin

ī

ya Br

ā

hma

ṇ

a

) to

see

what knowledge alone could not reveal, to find out how the world itself is made. Without this, all knowledge is pointless.

In the east, Bh

ṛ

gu came across men who were slaughtering other men. Bh

ṛ

gu asked: “Why?” They answered: “Because these men did the same to us in the other world.” He saw the same strange scene in the south. In the west there were men eating other men and sitting about, calmly. In the north as well, amid piercing cries, there were men eating other men.

When he returned to his father, Bh

ṛ

gu seemed speechless. Varu

ṇ

a looked at him with satisfaction, thinking: “Then he has seen.” The moment had come to explain to his son what he had seen. The men in the east, he said, are trees; those in the south are flocks of animals; those in the west are wild plants. Last, those in the north, who cried out while they ate other men, were the waters.

What had Bh

ṛ

gu seen? That the world is made up of Agni and Soma, of these two brothers. Brought up as two Asuras in V

ṛ

tra’s belly, they abandoned him to follow the call of another brother, Indra, and to pass over to the side of the Devas. Then “one of the two became the devourer and the other became food. Agni became the devourer and Soma the food. Down here there is nothing else than devourer and devoured.” And there are these two poles in everything that happens, without exception and at every level. But Bh

ṛ

gu discovered something else: the two poles were reversible. At a certain moment the positions will switch, indeed they

will have to

switch, because this is the order of the world. This explains why all that is said about Agni can also, at a certain moment, be said about Soma. And vice versa. A phenomenon that had already baffled Abel Bergaigne.

The revelations that Bh

ṛ

gu came across were set one within the other. First of all: the final act from which all others followed was the act of eating—or at least the act of severing, of uprooting. Every act that consumes a part of the world, every act that destroys. There is no neutral state, no state in which this doesn’t happen. The act of eating is a violence that causes what is living, in its many forms, to disappear. Whether grass, plants, trees, animals, or human beings, the process is the same. There is always a fire that devours and a substance that is devoured. This violence, bringing misery and torment, will one day be carried out by those who suffer it on those who inflict it. Such a chain of events cannot change. But the serious damage, the paralysis that this causes in those who become aware of it, can—we are told—be treated, remedied. This is Varu

ṇ

a’s knowledge, which Bh

ṛ

gu could not have learned without the impact of what he saw when he traveled the world—or the other world. And what was the remedy? The very act of perceiving that which is—and of manifesting it, not just with words, but with gestures: in this particular case, with a series of gestures to be carried out in the

agnihotra

, the most basic of all rites. Pouring milk into the fire—every morning, every evening—meant accepting that what appears disappears and that what has disappeared

serves

to give sustenance to something else, in the invisible. This was the lesson that Varu

ṇ

a sought to give his son.

It is easy to imagine from the story of Bh

ṛ

gu how the Vedic seers were skilled in detecting evil with supreme ease. Evil for them was already apparent at the moment when an axe first struck a tree or a hand uprooted a plant. It was metaphysical evil, inherent in everything that is forced to destroy a part of the world in order to survive, therefore above all in mankind. Compared with the moderns, who tend to limit evil to intentional acts, the Vedic seers had a conception of evil that covered a far wider area. And it included certain involuntary acts, as well as acts that just cannot be avoided if mankind wants to survive—for example, the act of eating. Evil is therefore everywhere and in everything. This explains why sacrifice is also everywhere and in everything. Sacrifice is the act by which evil is brought to consciousness, using an art learned from “he who knows thus.” That process in which evil is repeated and is directed, in its entirety, toward consciousness, through gestures and formulas, is the supreme remedy we can use in combating evil. Otherwise, all that remains is the mechanism revealed during Bh

ṛ

gu’s journey. Those who eat will be eaten. Those who slaughter will be slaughtered. Those who eat food will themselves become food.

The widespread atrocities, the endless and unrestrainable alternation between devourer and devoured, that Bh

ṛ

gu had encountered during his wanderings to the four corners of the world—and which his father, Varu

ṇ

a, taught him to overcome through the practice of sacrifice—never disappear, but indeed become threateningly apparent during the performance of the sacrifice itself. The sacrificial flames are like eyes, “they fix their attention on the sacrificer and focus on him.” What they would most desire is not the oblation, but the sacrificer himself. In front of the fire, the sacrificer feels he is being observed, stared at. The eye that is studying him is the eye of the fire. Before he himself formulates a desire, he feels it is the fire that desires him, his flesh. Here occurs the substitution, the redemption of Self: a last, swift operation to which the sacrificer resorts so as to offer the fire something instead of himself. The sacrificer offers food to avoid becoming food himself.

Bh

ṛ

gu encountered during his terrifying journey a world in which animals devoured people. But this wasn’t just a reversal of the order. It was also a lightning glimpse of the history of humanity, as if someone had at last taught Bh

ṛ

gu about some of his forebears. The period during which men, rather than devouring, were devoured is none other than the first, very long chapter of their history. Varu

ṇ

a wanted his son’s education to include this vision of the past, in the same way that a young boy might be sent to a good college to learn his country’s history. The Vedics were also this: they ignored history, more than any other people—but they remained in contact, more so than any other people, with remote prehistory, which showed through in their rites and in their myths.

* * *

In the Vedic landscape there is one object that evokes terror and veneration: the sacrificial post. Of all the emblems of that time, it is the only one still visible. In certain Indian villages, even today, a piece of wood can be seen sticking out of the ground, for no apparent reason. Madeleine Biardeau has found many of these in various parts of India, noting that they are that “post,”

y

ū

pa

, the “thunderbolt” of which the Vedic ritualists spoke. But why a “thunderbolt”? To understand this, we have to go back to a distant story:

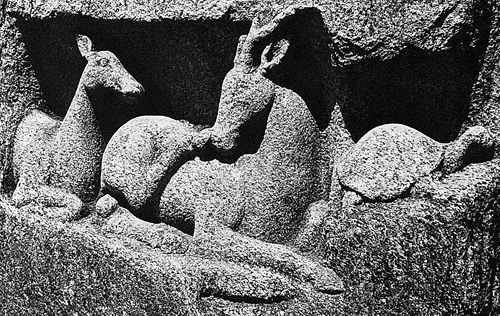

“There are an animal and a sacrificial post, for they never immolate an animal without a post. This is why: animals did not originally submit to the fact of becoming food, in the way that they have now become food. In the same way as man walks upright on two legs, they also walked upright on two legs.

“Then the gods noticed that thunderbolt, i.e., that sacrificial post; they put it in the ground and, for fear of it, the animals became crooked and four-legged, and so they became food, as today they are food, because they gave in: this is why they immolate the animal at the post, and never without a post.

“After having brought the victim forward and lit the fire, he ties the animal. This is why it is so: the animals did not originally submit to the fact of becoming sacrificial food, in the way that they have now become sacrificial food and are offered in the fire. The gods cage them: even caged in this way, they did not give in.