Armageddon (22 page)

To grasp the nature of the war against Germany, a crude rule of thumb is useful. Every mile of front on which the Americans and British fought, every German soldier deployed in the west, was multiplied three- or four-fold in the east. The disparity in casualties both suffered and inflicted during the last year of the war, when the Western allies were fighting in north-west Europe, was even greater. Eisenhower’s armies suffered some 700,000 casualties—killed, wounded and taken prisoner—between D-Day and the end; the Russians suffered well over two million during the same period. Between June 1941 and December 1944, Germany lost 2.4 million battlefield dead on the Eastern Front, against 202,000 men killed fighting the Americans and British in North Africa, Italy and north-west Europe together. The conflict between the Red Army and the Wehrmacht dwarfed the western campaign in scale, intensity and savagery.

Most Russian civilians spent the war years on the brink of starvation, working a sixty-six-hour week with one rest-day a month, receiving half the rations of Germans. Only vegetables grown in sixteen million urban gardens saved many people from death. In the course of the war, some 29.5 million Soviet citizens were drafted for service of one kind or another. By the autumn of 1944, more than 11.4 million men and women were serving in Stalin’s forces, 6.7 million of these with the active army. All statistics are unreliable, but the best available suggest that Soviet forces suffered total losses of 8.7 million killed, together with twenty-two million sick and wounded. These casualties were, of course, additional to at least eighteen million Soviet civilians who died.

It is important to qualify Soviet casualty figures. They fail to differentiate between those who were killed by the Nazis and those who died or were allowed to die at Moscow’s hands. Stalin’s agents continued killing and imprisoning “saboteurs” and “enemies of the state” in the hundreds of thousands. A quarter of all deportees in Siberian labour camps died of starvation in 1942—some 352,000 of them. Beria recorded the deaths of 114,481 in 1944, the year of victories. Around 157,000 men were shot for alleged desertion, cowardice or other military crimes in 1941–42 alone. Official Soviet rationing policy reflected indifference to the deaths from hunger of many weak and elderly people, since these were incapable of working or fighting. Throughout the territories now occupied by the Red Army the NKVD, Stalin’s all-powerful secret police and enforcing militia, was rounding up German civilians and PoWs in vast numbers, and dispatching them for labour service in the Soviet Union. Beria reported to Stalin in November 1944, for instance, that 97,484 German men between the ages of seventeen and forty-five and women between eighteen and thirty were being shipped to the Ukrainian mines from Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. Some of these could replace the German slaves who were dying in Soviet hands—6,017 during the first ten days of November alone, as Beria also recorded.

Stalin dominated Russia’s war more absolutely than Hitler controlled Germany’s. The Nazi empire was fatally weakened by the rivalry, self-indulgence, strategic folly and administrative incompetence of its leaders. In the Soviet Union, there was only one fount of power, from whom there was no escape or appeal. Ismay, Churchill’s personal Chief of Staff, recoiled from the cringing subservience of Russia’s generals when he first visited the Kremlin in 1941. “It was nauseating,” he wrote, “to see brave men reduced to such abject servility.” The Soviet Union’s defeats in 1941–42 were chiefly attributable to Stalin’s own blunders. In the years that followed, however, in striking contrast to Hitler, the master of Russia learned lessons. Without surrendering any fraction of his power over the state, he delegated the conduct of battles to able commanders, and reaped the rewards. He displayed an intellect and mastery of detail which impressed even foreign visitors who were repelled by his insane cruelty. He showed himself the most successful warlord of the Second World War, contriving means and pursuing ends with a single-mindedness unimaginable in the democracies. Terror was a more fundamental instrument of Russia’s war-making than of Germany’s. Even Stalin’s most celebrated marshals were never free from its spectre.

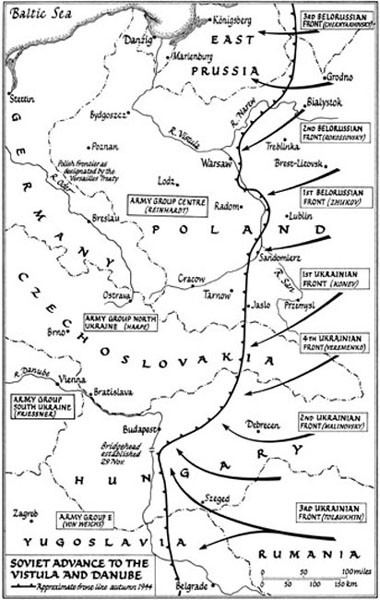

In the late summer of 1944, Soviet armies stood on the Vistula after accomplishing their most spectacular victories of the war. Yet, in the eyes of the West, admiration for Russia’s military achievement was overshadowed by horror prompted by events in Poland, to which Stalin responded with indifference, or worse.

WARSAW’S AGONY

O

N

1

A

UGUST,

on the orders of its commander, General Tadeusz Bor Komorowski, the Polish Resistance launched an uprising designed to wrest control of their nation’s capital from the Germans before the Russians arrived. At 1700 that day, “Hour Vee,” the red and white banner of Poland was hoisted above the Prudential building, Warsaw’s highest. The Poles signalled en clair to London: “The struggle [for the capital] has begun.” Among the first of many suicidally courageous actions, ninety-eight men of the “Stag” battalion sought to storm one German position armed only with revolvers. Just seven survived. Only one in seven of the 37,600 insurgents possessed weapons of any kind; 2,500 died on 1 August alone; 35,000 civilians were killed in the Vola suburb in the first week.

The “London Poles,” whose underground forces were known as the Resistance Army Krajowa, were goaded to act by nationalist fervour and by a radio broadcast on 29 July from Stalin’s communists, the “Lublin Poles.” This called for a people’s rising against the Nazis, and asserted that Russian help was at hand. Bor Komorowski believed that if the “London Poles” failed to mobilize, they would forfeit any claim to govern their own country. His intention was not to assist the approaching Russians and Lublin Poles, but to pre-empt their hegemony. He expected the Red Army to reach Warsaw within forty-eight hours, though he believed that his forces might maintain their struggle for five or six days if necessary. In the most spectacular and indeed reckless fashion, the Polish commander wanted it both ways: the success of his revolt hinged upon receiving Russian military support, while its explicit objective was to deny the Soviet Union political authority over his country.

The British Chiefs of Staff, recognizing their own inability to provide assistance, declined to offer the Poles any directive or guidance about their actions one way or the other. This, too, was extraordinarily irresponsible. Three months earlier the British Joint Intelligence Committee had concluded that, if the Poles carried out their long-planned uprising, it was doomed to failure in the absence of close co-operation with the Russians, which was unlikely to be forthcoming. It seems lamentable that, after making such an appreciation, the British failed to exert all possible pressure upon the Poles to abandon their fantasies. The Red Army made no move westward in support of the Rising. The scene was set for a tragedy.

On 31 July, the Japanese ambassador in Berlin had informed Tokyo that the Germans would not seek to hold Warsaw to the last. Withdrawal was indeed the Wehrmacht’s intention in the face of an envelopment by the Red Army; when this later came, Warsaw was scarcely defended. In August, however, confronted instead by domestic insurgency, the Nazis’ loathing and contempt for the Poles provoked them to exploit an opportunity to diminish the numbers of these troublesome people, and to reassert German authority. Military desirability and political inclination marched together. The Germans assumed that the Rising was orchestrated with the Soviets, and would soon be followed by a Russian link-up with the Resistance in Warsaw, which should be thwarted. Even in the last months of his empire, Hitler’s zeal in fulfilment of ideological doctrine never flagged. His business with the Jews was almost complete. The Nazis’ eagerness for innocent blood increased, rather than diminished, as their grasp upon power grew more precarious. German commanders, notably Heinrich Himmler, somehow scraped together forces to suppress the Rising. The Germans addressed their task with absolute ruthlessness. During the sixty-three days that followed, some 10,000 Resistance fighters died, along with 250,000 civilians—a quarter of Warsaw’s population—many of these people massacred in cold blood.

Cossacks, paratroopers and SS units were thrown into the battle. They employed flamethrowers, siege mortars, gas, explosive-carrying robots and systematic flooding of the Poles’ underground refuges. Much of Warsaw was reduced to rubble by bombardment. The surviving inhabitants were driven out into the countryside or shipped to concentration camps. The men of the SS, and especially the Dirlewanger Brigade, surpassed even their record in Russia of pillage, rape and mass murder, overlaid with sadism. The wounded were machine-gunned. Prisoners were hurled from the windows of apartment buildings. Polish women and children were used as human shields for the advance of German troops. On 5 August Hans Frank, the Nazi governor, reported to Berlin: “For the most part, Warsaw is in flames. Burning down the houses is the most reliable means of liquidating the insurgents’ hide-outs.” Hitler awarded Knight’s Crosses to Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski and Oskar Dirlewanger for their roles in recapturing the Polish capital. It is a measure of the savagery of the forces suppressing the Rising that the Nazis themselves shot the commander of the RONA Brigade, a unit of Russians serving in German uniform. Its anarchic brutalities became an embarrassment even to Himmler. The Germans lost 9,000 dead in Warsaw in the first three weeks of the Rising, amid merciless street fighting. “Kamil” Baczynski, one of many Polish poets who flourished in those days, wrote before he was killed on 4 August:

O Lord of the apocalypse! Lord of the World’s End!

Put a voice in our mouths, and punishment in our hand.

The horrors of Warsaw highlighted the futility of any attempt by guerrillas to engage regular troops equipped with heavy weapons, artillery and armour. Though the Polish resisters were plentifully supplied with courage, most lacked essential military training. They were armed only with weapons parachuted from Britain, for many of which they possessed only a few magazines of ammunition apiece, together with such small arms and armoured vehicles as they could capture from the Wehrmacht. Lieutenant-General Wladyslaw Anders, commanding the Polish II Corps in Italy, was among those bitterly critical of the Rising. He was privately convinced that it must end in tragedy. He recognized, as others should have done at the outset, that irregular forces could neither defeat the armies of Hitler nor expect aid to do so from the Russians.

The Germans shrewdly grasped these realities. Ninth Army observed that “Army Krajowa considers ourselves and the Russians equally its enemies.” As early as 5 August, Ninth Army’s intelligence department suggested that “many civilians who were enthusiastic about the uprising are now having second thoughts . . . They fear that the city of Warsaw will suffer the same fate as the former Warsaw ghetto . . . They fear German revenge.” The insurgents’ leaders sought to inspire their own people and dispirit the enemy by feeding them upon fantasies: that 300 Soviet tanks were already advancing on Warsaw from the south-east; that Russian aircraft were only awaiting better weather to launch attacks in support of the uprising. Sceptical civilians remarked that the weather was not preventing the Germans from flying.

It has often been suggested that Stalin incited the Rising in order to induce the bitterly anti-communist Army Krajowa to immolate itself. This seems mistaken. The Lublin Poles’ appeals to their countrymen to revolt were of a piece with many other flights of radio propaganda rhetoric. The Soviet high command took them much less seriously than Bor Komorowski. A Western correspondent quizzed the Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky, commanding 1st Belorussian Front opposite Warsaw, about the broadcast. Rokossovsky shrugged: “That was routine stuff.” The Red Army’s logistics were drastically stretched after its summer leap westwards. For the first ten days of August, Rokossovsky’s armies were committed to stemming an energetic German counter-attack east of the Vistula. In the beginning, therefore, Moscow had good military reasons for refusing to make a dash upon the Polish capital. The Russians might also have pointed out that in the west Eisenhower resisted all appeals from the Dutch to change Allied military plans and drive north in the winter of 1944, to save occupied Holland from terrible sufferings. The political and military leaders of the U.S. and Britain insisted that the best service they could render to Holland was to maintain their strategy to defeat Germany as swiftly as possible. They refused to allow military operations to be deflected by short-term humanitarian considerations.

It might also be noticed that in Italy the Allied Commander-in-Chief General Sir Harold Alexander encouraged partisans to rise on the widest pos-sible scale in the summer of 1944, when it was believed that liberation of the whole country was imminent. With the coming of winter, and the Allies bogged down in the mountains, the partisans suffered terribly from German counter-measures. In November, Alexander felt obliged to reverse his earlier policy and urge the partisans to abandon open military activity until spring. In some areas upon which German repression fell most heavily, there was deep and lasting bitterness about Allied incitement to premature action, followed by failure to relieve the partisans before the Germans fell upon them. Alexander could plead military necessity for his actions—and inaction. So did Stalin. All the Allies behaved with considerable cynicism in encouraging armed resistance in occupied Europe while possessing no means of preventing inevitable German retribution. The consequences for Warsaw were, however, vastly more terrible than anything which took place in the west.