Armageddon (38 page)

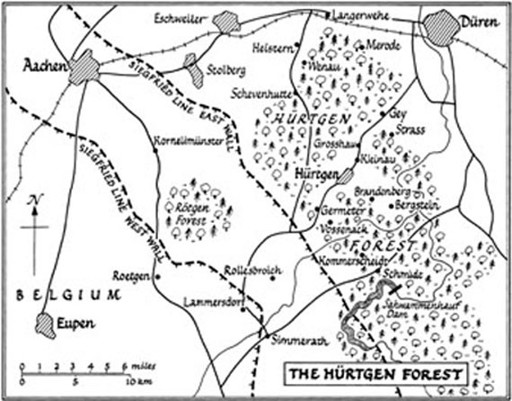

A few miles inside Germany, south-east of Aachen, lay a cluster of large expanses of wooded hills collectively known to the Americans as the Hürtgen Forest. The ridge lines, occupied by the German 275th Division, had been cleared of timber, which increased their dominance of the forests below. The 275th were poor-grade troops, who—like the garrison of Aachen—posed no plausible threat to the flanks of an American advance to the Roer. Yet the strange decision was taken that the Hürtgen should be cleared of Germans before another major attack eastwards was made. The American historian Russell Weigley has wisely observed: “The most likely way to make the Hürtgen a menace to the American army was to send American troops attacking into its depths. An army that depends for superiority on its mobility, firepower, and technology should never voluntarily give battle where these assets are at a discount; the Huertgen Forest was surely such a place.”

The U.S. 9th Division had suffered much unpleasantness during its early attempts to push through the Hürtgen in October, while Aachen was still in German hands. By 16 October, the formation had suffered 4,500 casualties in advancing two miles. At the beginning of November, the 28th Division of V Corps took over the task. Some early successes alarmed the Germans, and caused them to reinforce the area heavily. When the fresh U.S. 18th Infantry was pushed into an assault on 8 November, its battalions suffered 500 casualties in five days. The executive officer of one regiment of 28th Division wrote: “We’re still a first-class outfit, but not nearly as good as when we came across the beach. We have a great deal more prodding to do now.” In the thickly wooded country where the tracks had become quagmires, it could take six or eight hours to move rations and ammunition forward a mile or two. The 121st Infantry charged eleven men with refusal to return to the line—the first such case V Corps had recorded. An American officer said bleakly: “We are taking three trees a day, yet they cost us about 100 men apiece.”

Yet, instead of recognizing the folly of attacking on terrain that suited the Germans so well, Courtney Hodges reinforced failure. The Americans poured men into the long succession of battles which became known to all those who participated as “the hell of the Hürtgen Forest.” This network of woodlands some eight miles deep by twenty wide, almost impassable by tanks, eventually cost its attackers some 25,000 casualties. The terrain made it impossible to deploy American firepower effectively. The defenders’ weapons could cover every narrow access with devastating consequences for advancing infantry. “The trees were so dense that even when the sun shone, the day seemed gray,” wrote Lieutenant William Devitt of the 330th Infantry. “My first impression of the Hürtgen was the unremitting noise of the artillery. It sounded like a thunderstorm that went on and on without stopping.”

Devitt was a thoughtful twenty-year-old Minnesotan, posted to the 83rd Division in December as a replacement. “Until that time, the war hadn’t seemed very real or very deadly to me . . . I was anxious to learn what combat was like. I wanted to have the experience, probably to be able to talk about it after I got home.” As he took his platoon into the line, he was horrified by the sight of the 4th Division men his unit was relieving, their faces and field jackets caked in yellow mud: “They looked like a collection of ghosts . . . a grim lot, hollow-eyed from the constant pounding of shellfire, and fear of impending death.”

Many of the trees around their positions had been hacked short by shellfire. There were craters and fallen branches everywhere, together with German corpses, which fear of booby traps made the Americans unwilling to remove. Because it was hard to bring hot food forward, they lived chiefly off K-rations: processed meat, cheese, cooked eggs, crackers, dried fruit. Devitt’s company commander once asked him to breakfast, thinking he was doing the young officer a favour by offering him hot food, but the lieutenant hated the captain for making him risk the journey to his CP. Their SCR536 radios worked only intermittently among the trees. Incessant and dangerous effort was needed to splice broken field telephone lines. Devitt developed a personal obsession with toilet paper, because lack of it inflicted such humiliations when he, like most men, suffered an outbreak of “the GIs”—chronic diarrhoea. He carried one stash of paper in his helmet, another in his shirt pocket.

As an officer, he felt grateful that he had less time to be frightened than his men, because there was so much to do. The U.S. Army did not allow junior officers batmen—personal servants—as the British did, because it was thought demeaning to ask enlisted men to do such work. Omar Bradley was among those who deplored American scruples. He thought the British system militarily sensible, because overtaxed officers could do their jobs better if they did not also have to dig foxholes and prepare their own rations.

Devitt, like most young officers, learned a great deal from his veterans. His runner, a twenty-year-old from Indiana named Ernie Elliott, wounded in Normandy, put him wise to the shirkers: “Lieutenant, I wouldn’t be too soft on so-and-so—he’s always been a gold-bricker and will do whatever it takes to duck real work.” Yet Devitt found it hard to learn how to rally men subjected to the strain of incoming barrages. He recorded a shouted conversation in the Hürtgen as German shells smashed into the trees around his platoon’s foxholes:

“Lieutenant, will you come over here.”

“Yeah, what d’ya want?”

“It’s Smith. Can you talk to him?”

“Okay, just a second.”

He found the man huddled in a foxhole, weeping uncontrollably.

“Smith, just take it easy. You’ll be all right.”

“Lieutenant, I just can’t take it any more. I’ve just got to get out of here.”

“Well, Smith, we all want to get out of here, but we can’t. It’ll let up soon.”

After half an hour or so, the man recovered himself, and gave no more trouble. When a shell wounded two of his platoon, Devitt found himself struggling to put a field dressing on a large hole in one man’s chest as it smoked in the icy air, giving off a stink of burning flesh. The other wounded man said: “Lieutenant, he won’t make it. Come and help me.” Sure enough, a few moments later as the stretcher-bearers lifted the chest case, he shuddered and was dead.

A new officer arrived to take over a neighbouring platoon, where his sergeant, Haney, urged him to dig his foxhole deeper. The lieutenant ignored this suggestion. Soon afterwards a near-miss gave him a slight shrapnel wound in the hand. The officer leaped up, yelling to his NCO: “Look, Haney, that’s my ticket home! Talk about a million-dollar wound, this is it. Call the medic to put on a bandage, then it’s the rear for me. I’ve had enough of this place.” Devitt’s company suffered thirty-six casualties in a single week in the Hürtgen, without achieving anything of significance.

A

MAJOR

A

MERICAN

offensive began early in the afternoon of 16 November with an attempt to push eastwards from a start line north of the Hürtgen, along the so-called Hamich Corridor towards Cologne. Nothing did more to boost the precarious morale of the American attackers than the spectacle of their own fighter-bombers pounding the Germans. “It was a beautiful sight to us,” wrote a U.S. infantryman watching a P-47 strike. “We could see the tracers bouncing off their targets, then they would dig down and let their bombs go. For a second or two, it would look as if they were duds; then a grey geyser of dirt and smoke would erupt.” Inevitably, however, there were mistakes, and mistakes in wars cost lives. Again and again, especially amid the confusion of the woodlands, friendly aircraft strafed Allied positions, causing much bitterness and—more serious—corroding trust among units which had been hit, making them reluctant again to summon air support. Neither side had much idea exactly where the enemy was, except during an attack. The U.S. 28th Field Artillery fired 7,421 rounds of 105mm ammunition during the month of November in the Hürtgen. The regiment acknowledged, however, that most of these—6,520 shells—were blind and unobserved.

Even as the Hamich Corridor push was in progress, the unfortunate 26th Infantry were attacking inside the Hürtgen. Among the trees, the Americans suffered familiar, bloody difficulties in advancing a few hundred yards. In the corridor, where progress was made the lead elements found themselves under fire from German-held high ground on both sides. The first two days’ fighting reduced the lead battalion of the 16th Infantry to an average of sixty riflemen per company, less than half its established strength.

The U.S. 109th Regiment fighting among the trees was deemed close to collapse. Its survivors were withdrawn. The 121st Infantry was so battered that one company broke and ran under artillery fire. On 24 November, both this company’s commander and his battalion superior were relieved. In the next four days, two other company commanders and another battalion CO were sacked. Two days later, the regimental commander was also relieved, along with the 8th Division’s commander, Major-General Donald Stroh. No one could accuse the U.S. Army of tolerating failure in its officers. The anger of the higher command was understandable, since the 121st had suffered only sixty known dead in an attack which petered out without gaining a yard. Private Robert McCall, a Connecticut farmworker, was sent as a replacement to the 121st. As he and some bewildered comrades waited to be allocated to companies, they saw Weasel tracked vehicles carrying out wounded. McCall reflected on the likelihood that he would soon be taking the same route. The first casualty he saw was a sergeant who leapt into a foxhole as shelling started, causing a grenade to fall out of his belt, which exploded and killed him.

McCall took part in his first attack on 28 November. Catching a glimpse of a German helmet, he fired, and was rewarded by the sight of an enemy soldier as frightened as himself emerging from a hole, his upheld hands shaking. The Americans broke out of the woods and began to advance across open ground towards their objective. They were stopped by heavy fire. “To stay where we were would have been suicide, so the whole outfit ran back across the field.” McCall crawled into a foxhole recently vacated by the Germans, and was disconcerted to hear a cry of “

Kamerad!

” from the next trench. He saw a German helmet, and fired. Examining the corpse of the first man he had ever killed, McCall removed his watch and wallet. The following day, as his unit advanced into Hürtgen, he heard the shriek of an incoming shell. “Next instant, it felt like someone had hit me in the small of my back with a club.” Two men dragged him to the roadside and left him for the medics. A few days later, he was on his way home to Connecticut. After a year of training, McCall’s active service career had ended after just ten days in the line. Many men thought him lucky, and so indeed did he himself.

The 121st’s total casualties were around 600 out of a strength of 3,000, but most of these were combat-fatigue cases. Its commanders concluded that the regiment had succumbed too readily to the misery of the Hürtgen. It was striking to contrast what the best American troops could achieve with the performance of their less effectual brethren. “Attacking forces were interfered with by mud, rain and sleet,” wrote Sergeant Forrest Pogue with V Corps. “Enemy personnel were not of a high quality. The forces consisted principally of regiments of numerous units that had been disorganised in France. Numerous

Kampfgruppen

were formed of exceptionally young or old soldiers. Poor observation interfered with the use of artillery by the Americans.” When repeated efforts failed to seize a peak named Castle Hill, on 7 December a battalion of the Rangers, who had achieved miracles on D-Day, was sent to do the job. They stormed the hill. Powerful artillery support enabled them to hold it against ferocious German counter-attacks. By the day’s end, only twenty-five men remained in action among the two Ranger assault companies.

Lieutenant Tony Moody joined the 112th Infantry in the Hürtgen late in November. “It was very cold and very wet, and I had lost my bedding roll.” He met his company commander for the first time in the middle of an incoming barrage, which frightened him considerably. He was then taken to meet his platoon: “Their morale was pretty bad. I’m sure we inflicted as many casualties on the Germans as they did on us, but somehow they didn’t seem to get as upset about them as we did. We lost quite a few combat fatigue cases.” Moody was a twenty-one-year-old graduate in architecture from Missouri, with ambitions to be an artist. His first hard test of leadership, he felt, came when a man returning from the latrines failed to hear a challenge and was shot dead by an American sentry. Writing to the man’s wife, Moody struggled to find words to make her husband’s death sound less ugly and futile.

Unglamorous jobs incurred inflated dangers. Prominent among these was that of signal wireman. It was critical to maintain communications between the forward positions and unit headquarters. Telephone lines were constantly severed by fire. Wiremen had to find the breaks and repair them, often while bombardment persisted. “Telephone wiremen were the first to die in every battle,” observed Captain Karl Godau of 10th SS Panzer. Private Ralph Gordon of the U.S. 18th Infantry was called out at 0300 one night: “It was so dark that it was impossible to see your hand in front of your face, and the only reason I knew where I was, was that I followed my wire line till I reached the breaks. I must have fallen down a dozen times, and one time my pistol fell from my belt when I walked into a trench. I spent 15 minutes feeling around in the dark trying to find the pistol, and during those minutes I cursed everyone that had anything to do with starting the war.”