Armageddon (61 page)

Do you see what a complicated thing is man’s soul, man’s psyche? Well then, imagine a man who has fought from Stalingrad to Belgrade—over thousands of kilometres of his own devastated land, across the dead bodies of his comrades and dearest ones? How can such a man react normally? And what is so awful in his having fun with a woman, after such horrors? You have imagined the Red Army to be ideal, and it is not ideal, nor can it be . . . The important thing is that it fights Germans . . . The rest doesn’t matter.

Russians have often displayed a spirit of indulgence towards barbarities within their own society which does not extend to those committed against their people by foreigners. Why should it do so? Hitler and his armies had aspired to enslave the Russian people, no more and no less. Millions of Russian captives in Germany had already died, and millions more had become serfs of German farmers, factory-owners, householders—some of them in East Prussia. Stalin’s people knew this. The Red Army had performed feats which would have been unthinkable for Western soldiers, and paid a price that no American or British army would have accepted. As Russians fought their way painfully west through 1943 and 1944, every man in the ranks saw the legacy of German occupation: blackened ruins, slaughtered civilians and ravaged countryside.

In 1945, in Soviet eyes it was time to pay. For most Russian soldiers, any instinct for pity or mercy had died somewhere on a hundred battlefields between Moscow and Warsaw. Half a century earlier, the great Gorky had observed the paradox that a group of Russians who might individually be humane, decent people were capable, when gathered in a mob, of extraordinary bestiality. An ethos of hatred and ruthlessness had been deliberately cultivated in the Red Army. It would be wrong simply to dismiss Soviet soldiers as savages. Though there were many primitive people in the Red Army’s ranks, there were also cultured and thoughtful ones, some of whom this narrative seeks to bring to life. It is indisputable, however, that in 1945 the Red Army considered itself to deserve licence to behave as savages on the soil of Germany, and its men exploited this in full measure. They dispensed retribution for the horrors that had been inflicted upon the Soviet Union of a kind familiar to Roman conquerors, who also thought of themselves as a civilized people.

Dwight Eisenhower painfully exposed himself to the charge of naivety by the description of the Russian soldier in his post-war memoirs: “In his generous instincts, in his devotion to a comrade, and in his healthy, direct outlook on the affairs of workaday life, the ordinary Russian seems to me to bear a marked similarity to what we call an ‘average American.’” If the detail of what took place in eastern Europe was still unfamiliar to SHAEF’s Supreme Commander, by 1948 (when his memoirs were published) he must have possessed a general understanding of the Red terror which disfigured the Allied victory over Germany. His remark must be considered an exceptionally unhappy example of political tact.

To this day many Russians—and indeed the Moscow government—deny the scale of the cruelties the Red Army is alleged to have inflicted in East Prussia and Silesia, and later beyond the Oder. Private Vitold Kubashevsky, for instance, who speaks frankly about every other aspect of his experiences with 3rd Belorussian Front, still refuses to discuss what he saw in East Prussia. Yet eyewitness testimony is overwhelming. “All of us knew very well that if the girls were German they could be raped and then shot,” wrote Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, who served as a Soviet artillery officer in East Prussia. “This was almost a combat distinction.” It is striking that such a man as Michael Wieck, the young Königsberg Jew who welcomed the Russians as his saviours, bears witness to the horrors they committed. Even Professor John Erickson, whose monumental history of the Red Army is the most admiring by any Western author, acknowledges its conduct in East Prussia: “Speed, frenzy and savagery characterised the advance . . . Villages and small towns burned, while Soviet soldiers raped at will and wreaked an atavistic vengeance . . . families huddled in ditches or by the roadside, fathers intent on shooting their own children or waiting whimpering for what seemed the wrath of God to pass . . . men with pity for no one.”

The Russians themselves, of course, paid most heavily of all for their policy of fire and the sword. A belief that there could be no purpose in surviving Soviet victory overtook much of the German Army in the east. The huge casualties Stalin’s nation suffered during its drive into Germany reflected, in considerable part, the fact that the victors offered the vanquished only death or unimaginable suffering. Even after sixty years, it is difficult to extend to the German people the pity due to innocent victims of Nazi tyranny. However bitterly many Germans may have regretted this by 1945, Hitler and Nazism were the creations of their society. The horrors the Nazis inflicted upon Europe required the complicity of millions of ordinary Germans, merely to satisfy the logistical requirements of tyranny and mass murder. Yet now they saw the first fruits of retribution.

“We were forced to leave a land where generations of our families had been born, where they had lived and died, which they had loved and tilled the land and yes, defended it against many enemies,” wrote Graf Franz Rosenburg, one of East Prussia’s landowners, venting the bitterness of his entire people. “Everything we cherished was lost in a single night!” The Red Army was responsible for massive destruction of art treasures, almost certainly including Peter the Great’s Amber Room, though, like so much else, this was subsequently blamed on the Nazis. At his post on the shore at Pillau, Private Vitold Kubashevsky of the Red Army watched curiously as the tides came in. Each one bore with it a harvest of German corpses, a flotsam of failed fugitives, to swing to and fro upon the waves beside the

Heimat

they loved so much, and which was now as irredeemably forfeit as their own lives.

At Yalta on the evening of 6 February 1945, in a spasm of compassion Churchill said to his daughter Sarah: “I do not suppose that at any moment of history has the agony of the world been so great or widespread. Tonight the sun goes down on more suffering than ever before in the world.” Churchill knew little, when he spoke, about what was taking place in East Prussia. Yet its people’s fate formed a not insignificant part of his vision.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Firestorms: War in the Sky

THE BOMBER BARONS

B

Y THE WINTER

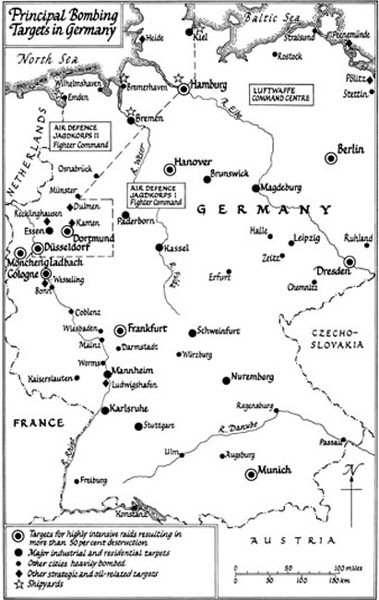

of 1944, bomber operations against Germany had attained awesome destructive power. On 14 October, U.S. and British air forces launched a joint operation, Hurricane, to demonstrate to the Germans—and also to the Allied Chiefs of Staff—the scale of force they could unleash in a single twenty-four-hour period. First, in daylight, 1,251 aircraft of the U.S. Eighth Air Force attacked rail centres at Saarbrücken, Kaiserslautern, and Cologne, escorted by 749 fighters. Six bombers and one fighter were lost. Meanwhile, 519 Lancasters, 474 Halifaxes and 20 Mosquitoes of RAF Bomber Command mounted a daylight raid on Duisburg, escorted by British fighters. They dropped 4,918 tons of bombs, for the loss of thirteen Lancasters and one Halifax. With the coming of darkness, a further 498 Lancasters, 468 Halifaxes and 39 Mosquitoes again attacked Duisburg in two waves, two hours apart. A total of 4,540 tons of explosives and incendiaries were dropped, for the loss of five Lancasters and two Halifaxes. German casualties in the city were unmeasured, but heavy. On the same night, 233 Lancasters and seven Mosquitoes struck Brunswick. Only one Lancaster was lost. The old city centre of Brunswick was totally destroyed—an area of 370 hectares—and 561 people died. It was never thought necessary for Bomber Command to visit Brunswick again.

Meanwhile—still during the night of 14 October—the RAF sent twenty Mosquitoes to Hamburg, sixteen to Berlin, eight to Mannheim and two to Düsseldorf on nuisance raids, designed to drive the inhabitants of those cities into their shelters and force the defenders to expend weary hours manning guns and searchlights. One Mosquito was lost over Berlin. Another 141 bombers manned by crews completing operational training launched a diversionary sweep across the North Sea. One hundred and thirty-two RAF aircraft mounted electronic counter-measures operations, to frustrate German radar and communications. By the time the last aircraft turned homewards, a total of 10,050 tons of bombs had been dropped on Germany, the highest total attained in any single twenty-four-hour period of the war.

Yet what did all this mean? What were the fruits of this huge effort, which absorbed a substantial part of the war-making powers of the United States, and consumed a proportion of Britain’s industrial capacity equal to that devoted to the entire British Army? The bombing of Germany destroyed almost two million homes and killed up to 600,000 Germans, many of these in the war’s closing months. From beginning to end, the Western allies encompassed the deaths of two or three German civilians by bombing for every German soldier they killed on the battlefield. Yet did this shorten the conflict, or achieve an impact commensurate with its human and industrial cost both to the victors and to the vanquished?

Between 1918 and 1939, the apostles of air power had preached the gospel of strategic bombing, which they argued could render redundant the bloody struggles between armies on the ground by destroying the industries essential to a nation’s war effort. Airmen in Britain and America also saw in bombing the key to their own struggle for independence from the older fighting services, proof that an air force was much more than a mere appendage of armies and fleets. Before the war, many European politicians, not to mention the public, were much alarmed by visions of cataclysm inflicted from the skies, and by such early manifestations of the totalitarian states’ contribution to history as the destruction of Guernica and Nanking, Warsaw and Rotterdam.

From 1940 onwards, however, the combatants surprised themselves by learning to live with the consequences of aerial assault. They found that bombing inflicted great misery, hacked brutally at the culture of centuries, and imposed pain on industry. It would be ludicrous to imply that the German people found the experience of being bombed acceptable, or to deny that Hitler’s war production suffered not only from damage to plant, but also from absenteeism and chronic dislocation to the lives of the labour force. After the Luftwaffe had tried and failed to break the British in the blitz of 1940–41, however, a more rational and less absolutist view of bombing supplanted pre-war expectations of doom, among all save the Allied air chiefs.

The airmen remained messianically committed to strategic bombing. In America, the USAAF argued that the Luftwaffe had failed against Britain because it had not systematically addressed precision targets vital to the nation’s infrastructure—oil, transport links, the power grid. The RAF believed that the German attack upon Britain had merely lacked the sustained weight to strike a mortal blow. In 1941, the Chief of Air Staff Sir Charles Portal demanded from Churchill a commitment to create a force of 4,000 heavy bombers, a fantasy which remained unfulfilled even in 1945 by the combined might of the RAF and USAAF’s squadrons in Europe. Churchill was always sceptical about the airmen’s visions. “All things are always on the move simultaneously,” he wrote to Portal in October 1941, “the Air Staff would make a mistake to put their claims too high.”

Throughout 1940 and 1941, however, the RAF’s bomber offensive was the only means by which Britain could carry the war to Germany. The prime minister threw his weight behind the creation of a great bomber force. Unless the British could convince themselves that air attack might eventually defeat Hitler, what course was open to them save a negotiated peace? Even Churchill at his most optimistic never supposed that Britain’s armies could alone beat the Axis. It was ironic that the RAF thus set about attempting to do to the Germans exactly what the Luftwaffe had signally failed to achieve against Britain. The bomber offensive was to be lavishly endowed with ironies.

In 1942, even as the skies over Britain brightened immeasurably with the accession of the United States and Russia as allies, the Combined Chiefs of Staff agreed that bombing remained vital, because it would be years before the Anglo-American armies could undertake a decisive land campaign. In the secrecy of Whitehall, the British were obliged to acknowledge the failure of their precision air attacks upon German industrial targets, for which the RAF’s night bombing force was too weak and ill-equipped. They embarked instead upon the policy of “area bombing”—a systematic assault upon the cities of Germany with a mixture of high-explosive and incendiary bombs, designed to break the morale of the enemy’s industrial workforce, as well as to destroy his means of production. For the rest of the war, this offensive gathered momentum, as the RAF’s Bomber Command grew in strength, despite heavy losses of British aircrew—56,000 highly trained personnel were killed by the war’s end, almost double the fatal casualties suffered by the American bomber men in Europe.

The USAAF’s Eighth Air Force was slow to build up forces in Britain with which to launch its own precision campaign. In 1942, it confined itself largely to attacking short-range targets in France. In 1943, when formations of B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators began to attack Germany, their losses against German fighters were alarming, sometimes horrendous. In the worst single month, October 1943, the Americans lost 186 heavy bombers—a 6.6 per cent casualty rate. In January 1944, during the RAF’s so-called Battle of Berlin, Bomber Command lost 314 aircraft, or an average 5 per cent of its strength on every raid. Since a British bomber crew was obliged to carry out thirty operations to complete a tour of operations, and an American crew twenty-five, it needed no wizard of odds to compute that an airman was more likely to die than to survive his personal experience of bombing Germany.