Armageddon (85 page)

The Germans, even in these last weeks of the war, addressed the uprising with unstinting ferocity. Hitler signalled personally to demand that “an example should be made of the rebels.” Some 3,600 men of the Wehrmacht were committed, in a battle that lasted more than a fortnight. The C-in-C Netherlands reported to Berlin on 17 April: “Extremely fierce fighting from strongpoint to strongpoint . . . success only possible if all available artillery and other heavy weapons are employed.” Yard by yard, the Germans forced back the mutineers. A German officer who led the way into the local hospital shot five badly wounded Georgians in front of a Dutch nurse. The last fifty-seven mutineers capitulated on 20 April. “We had risen against the Hitler tyranny, we had made great sacrifices,” one of the few survivors wrote bitterly, “but instead of receiving help we were betrayed and abandoned.” The captives were stripped naked, forced to dig their own graves, then shot. The last four were kept alive long enough to fill in the holes. A total of 117 local Dutch people, 550 Georgians and 800 Germans perished in the Texel battle, which went entirely unremarked outside Holland, both then and later. This bloodbath ended barely a week before Hitler’s death.

The agony of Holland was assuaged by the surrender of von Blaskowitz’s forces on 5 May, yet it became the work of months to claw back the nation from the abyss of starvation, aided by enormous Allied air drops of food—Operation Manna. If the Dutch were not confined behind barbed wire, their sufferings were at least as great as those of most Allied prisoners of war. Incredibly, the occupiers continued to murder Dutchmen not only after Hitler’s death, but in their rage and bitterness after VE-Day. Germans indulged an orgy of looting and killing before the Canadian liberation forces arrived. On 8 May, twenty-year-old Elsa Caspers remonstrated with an SS man standing over three bodies, which he said were those of “terrorists.” Elsa, a Resistance courier, said: “Surely you must know the war is over?” The German sneered: “We did it just for fun.” Annie van Beek, who was twenty-three in 1945, retained for the rest of her life her bitterness towards the Germans: “They took away what should have been the best years of my life. They gave us that awful last winter. My fiancé spent three years as a prisoner of war. My younger brother died in one of their terrible camps.” If the law had been enforced against all Germans who committed crimes against humanity in the countries occupied by Hitler, post-war executions on a Soviet scale would have been necessary. The Dutch experience of war in the winter of 1944–45 was as terrible as that of any nation in western Europe. To the very end, the Germans showed no hint of mercy to millions held in the Nazi maw.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Collapse in the West

EISENHOWER’S DECISION

T

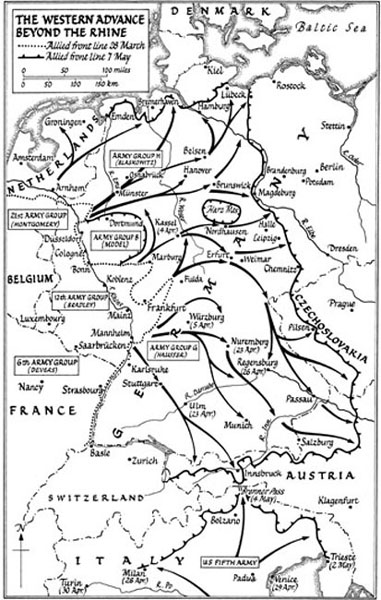

HE SEIZURE

of the bridge at Remagen, one of the most melodramatic episodes of the Allied campaign, was followed by a march to victory on the Western Front that ended in anticlimax, for reasons that were inescapable. Bradley’s forces staged their breakout from the Remagen bridgehead on 25 March, almost three weeks after the crossing was taken. Here again, caution had prevailed. After a slow start, making four or five miles a day, the pace of the advance quickened. German resistance was slight. Bradley, who had never achieved a successful envelopment, now became passionately committed to encircling the Ruhr and at last making the massive capture of Germans which had eluded his armies since Normandy. His plan was that the U.S. First Army, pushing up from the south, should link with Simpson’s Ninth, swinging south-east from Wesel. It seemed to some observers strange that, after Eisenhower had repeatedly asserted the primacy of Berlin as the focus of all Allied hopes and aspirations since June 1944, the Americans should now throw overwhelming force behind a limited operation 250 miles west of the capital. The Ruhr’s strategic and industrial importance stemmed from its production of raw steel rather than finished munitions. At this stage of the war, it was implausible that any steel leaving the presses could be converted into weapons in time to be employed by the Wehrmacht. Russell Weigley is among the fiercest American critics of Bradley’s decision to concentrate on the Ruhr, “whose strategic significance was . . . essentially nil.” Yet Bradley judged the capture of the remains of Army Group B, his adversary since Normandy, as the most substantial objective for his armies. In the light of subsequent events, he may have been right.

Some Allied units encountered stubborn local resistance. There was an unhappy episode on 30 March: as the U.S. 3rd Armored Division barrelled confidently eastwards, tanks from the SS Panzer Training School at Paderborn struck hard at the American column. A Tiger smashed into the jeep of the division’s commander, the much admired Maurice Rose. The general was trapped on the road. He reached down to his waist, apparently to unbuckle his pistol belt to surrender. A German shot him. It was fancifully suggested that Rose had been deliberately killed because he was Jewish, indeed a rabbi’s son. In truth, the general was merely a victim of the chance of battle.

In the days that followed, the Americans fought some fierce little battles with Germans seeking to escape capture, but nothing seriously impeded their advance. Whatever delays some spearheads suffered, overall American casualties were small, and armoured columns ate up the miles eastwards. In the first days of April, Bradley committed eighteen American divisions to tighten the Ruhr noose on 317,000 men, the ruins of Army Group B. As the Americans closed in, dogged German resistance persisted. Ridgway dispatched one of his officers to Model’s headquarters under a flag of truce, proposing surrender. Model declined, declaring that his oath to the Führer required him to fight to the end. Ridgway told the German colonel who brought this message to his CP that he was free to return to his own lines. The colonel responded prudently that he would prefer to become a prisoner of war. Lieutenant Rolf-Helmut Schröder, a staff officer at Model’s HQ, found himself carrying orders to corps commanders for renewed attacks. One general said furiously: “This is all nonsense—it’s crazy!” Schröder shrugged apologetically: “I don’t make the plans—I just bring them from Army headquarters.” The other corps commander seized the operation orders which the young officer brought and tossed them into the wastepaper basket.

When the Germans in the Ruhr pocket finally abandoned the struggle on 18 April, the principal challenge for the Americans was to marshal their captives and put them into PoW cages. Flying in a B-26 high above the battlefield on 25 April, Lieutenant Robert Burger saw below him “what looked like a dark plowed field . . . To my disbelief, it proved to be acres of massed humanity. There must have been hundreds of thousands of German PoWs packed together closer than a herd of cows. How they were fed or kept clean, I will never know. This was probably the largest audience I will ever have—as we flew over, all those captives’ eyes looked up. I don’t doubt some of them were ones that formerly shot at us.”

Since advancing out of the Remagen bridgehead, it had taken a month to complete the Ruhr envelopment. Ninth Army suffered around 2,500 casualties of all kinds, and First Army some three times that number. Model, Army Group B’s commander, walked away into a forest and shot himself on 21 April.

B

ECAUSE

D

WIGHT

E

ISENHOWER

presented a benign face to the world, even his commanders sometimes underestimated the pressures upon him, the relentless tensions under which he laboured. In mid-March, some of his staff feared that he was close to a nervous breakdown, a condition only slightly ameliorated by a forty-eight-hour break in the South of France. When Ike’s son John arrived in Europe, assigned as an infantry platoon leader, Bradley insisted that the boy should instead be given a staff job. The previous autumn, the son of General “Sandy” Patch had been killed in action while serving with his father’s own U.S. Seventh Army. The blow devastated Patch, and for some time rendered him all but unfit for his duties. Eisenhower’s subordinates were desperate to ensure that no such emotional burden was laid upon the Supreme Commander. To John Eisenhower’s deep embarrassment, he was kept out of combat. His father now faced decisions as important as any since Normandy.

Montgomery abruptly informed SHAEF on 27 March that he intended to drive for the Elbe, with the British Second Army’s left wing touching Hamburg and the American Ninth Army’s right brushing Magdeburg: “My headquarters will move to Wesel–Münster–Wiedenbrück–Herford–Hanover—thence by autobahn to Berlin, I hope.” This signal infuriated Eisenhower. Next day in his headquarters at Rheims, he received a message from Marshall in Washington warning of the importance of clarifying demarcation lines with the Russians, to avoid any danger of an embarrassing, perhaps dangerous collision when the Eastern and Western allies met. The two communications forced upon Eisenhower some immediate decisions. He dealt first with the British field-marshal. Beyond arrogating to himself the Supreme Commander’s authority to make strategic choices, Montgomery’s assumption that the U.S. Ninth Army would remain under his command seemed intolerable. Eisenhower signalled 21st Army Group that, with the Rhine crossing operation complete, Ninth Army would revert to 12th Army Group’s command on 2 April. Omar Bradley thus became master of 1.3 million men in four armies. Eisenhower decreed that Bradley’s forces should address the main axis of advance eastwards. The 21st Army Group would fulfil a subsidiary role, covering the Americans’ left flank, while Devers’s 6th Army Group performed the same function on the right. It is unlikely that it cost the Supreme Commander much pain to give orders that would distress Montgomery.

Eisenhower’s next action roused the fury of Churchill and has provoked controversy for sixty years. Without further reference to his political and military superiors, on his own initiative he sent a personal message to Stalin stating that his armies had no intention of advancing to Berlin. SHAEF hoped, he said, that the Anglo-Americans would meet the Russians on an axis Erfurt–Leipzig–Dresden—which meant around the Elbe, at least forty miles west of Berlin. He copied his cable to the Combined Chiefs of Staff.

Churchill personally telephoned Eisenhower on 29 March to express his dismay that a field commander should have communicated so vital a decision direct to Stalin, without prior reference to the Anglo-American leadership. The British prime minister asserted his strong belief in the importance of Berlin as the final destination of the Anglo-American armies. Yet the American Supreme Commander no longer felt obliged to display the deference to the British prime minister which had seemed appropriate a year or two earlier. Churchill was visibly weary and audibly testy. Eisenhower was well aware that the wishes of the British government no longer exercised decisive influence where it mattered—in Washington. “The PM is increasingly vexatious,” Eisenhower told Bradley. “He imagines himself to be a military tactician.” Churchill said to Brooke: “There is only one thing worse than fighting with allies, and that is fighting without them.”

One line in Eisenhower’s signal to the combined Chiefs of Staff has remained the focus of fierce debate since 1945. He asserted blandly that “Berlin has lost much of its former military importance.” He made plain that he had no intention of assaulting Germany’s capital, unless he was instructed to do so. “I am the first to admit that a war is waged in pursuance of political aims,” he wrote on 7 April, “and if the chiefs of staff should decide that the Allied effort to take Berlin outweighs purely military considerations, I would cheerfully readjust my plans and my thinking so as to carry out such an operation.” No such decision was forthcoming. Marshall endorsed Eisenhower’s decision, overriding the remonstrations of the British. The dying Roosevelt did not intervene.

Back in November 1943, the president had asserted that “there would definitely be a race for Berlin. We may have to put United States divisions into Berlin as soon as possible.” The president sketched a plan for the post-war occupation of Germany, in which the capital stood in the American zone. By April 1945, Roosevelt’s 1943 Berlin vision had evaporated. This was a reflection of the president’s unwillingness to intervene in issues of military strategy, save on the largest questions; his failing health; circumstances on the German battlefield which had been quite unforeseeable sixteen months earlier, with the Russians further forward than anyone had envisioned; the reluctance of the U.S. Chiefs of Staff to make military decisions for political purposes; and the desire of the U.S. State Department to conciliate Moscow.

At the time of Eisenhower’s exchanges with London and Washington, however, Bradley had no more knowledge than Montgomery of Eisenhower’s decision—and it was overwhelmingly a personal one—to forswear any attempt to reach Hitler’s capital. On 3 April, 12th Army Group’s commander was still telling his own generals that for the last big advance of the war Ninth Army would head for Berlin, while First Army struck south-east for Leipzig. On 4 April, Simpson was ordered to “exploit any opportunity for seizing a bridgehead over the Elbe and be prepared to continue to advance on Berlin or to the north-east.” As late as 8 April, Eisenhower visited Major-General Alexander Bolling, commanding the 84th Division in Hanover, and asked him where he was headed next. “General . . . We have a clear go to Berlin and nothing can stop us,” responded Bolling. “Keep going,” said Eisenhower encouragingly, putting a hand on Bolling’s shoulder. “I wish you all the luck in the world and don’t let anybody stop you.” It seems extravagant to interpret this with hindsight, as Bolling did at the time, as a tactical mandate to drive for Hitler’s capital; rather, these were simply a commander’s loose words of encouragement to a junior subordinate. The conversation reflects the somewhat insouciant manner in which Eisenhower seemed to his generals to address the Berlin issue, together with his familiar imprecision of military purpose.