Armageddon (94 page)

Yet, fortunately for the Red Army, there were some men still eager for glory. Lieutenant Nikolai Dubrovsky’s commanding officer of the 136th Independent Artillery Regiment rushed his unit forward to Zhukov’s front as soon as he was ordered to move there from East Prussia. The colonel was desperate to qualify for the Berlin campaign medal. Although Dubrovsky himself had been drafted at sixteen in 1942, he had thus far been fortunate enough to see no action. He felt far less emotionally committed to the struggle than many men: “I wanted to fight, because everybody else was fighting, but I felt no hatred for the Germans—I was too young to be embittered.” The gunner officer was lucky, first, to come from eastern Russia, which the 1941–42 German onslaught never reached; and second, to serve in a heavy artillery unit, where personal risk was small. From his brigade’s Fire Control Centre, Dubrovsky was responsible for calling down 152mm howitzer fire on Hitler’s capital from a range of twelve miles.

In this last period of the war, the Soviets’ reputation for savagery cost them dearly. In the west, many German soldiers were embracing captivity. All but the most committed Nazi fanatics knew that, if they picked the right moment to surrender, they were likely to survive, and to be humanely treated. On the Eastern Front, by contrast, there was not only a generalized fear about the behaviour of the Russians towards Germany, but a personal one about any man’s slender prospects of surviving captivity. “Many Germans seemed to feel that they were going to die anyway, so they might as well die fighting,” acknowledged Lieutenant Pavel Nikiforov, a Soviet reconnaissance officer. The Red Army would not have stood at the gates of Berlin in April 1945 but for its ferocious fighting spirit. Yet the dreadful casualties of the last battles might have been greatly diminished had not the Germans fought with the courage of despair. The Stavka seemed belatedly to recognize this, by an order of 20 April calling for “a change of attitude towards prisoners and civilians. We should treat Germans better. Bad treatment of Germans makes them fight more stubbornly and refuse to surrender. This is an unfavourable situation for us.” Yet it was far, far too late to alter the mindset of six million men, fostered over four years of merciless struggle.

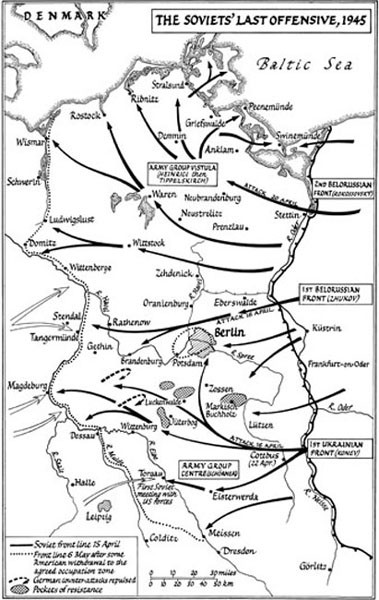

Zhukov’s and Konev’s assaults across the Oder began in darkness early on 16 April. Forty-two thousand Russian guns launched a massive bombardment, which they would sustain through days to come. More than seven million shells had been stockpiled. There was little scope for deception when there was no leaf on the trees and the ground was too waterlogged to dig deep. Every German knew full well where the Russians were heading, as Stalin’s forces began to close upon Berlin across an arc of advance that extended 235 miles. Soviet aircraft launched the first of 6,500 bombing and strafing sorties against German positions beyond artillery range. As flares of every hue shot into the sky to give the signal, the night crossing of the river began. The Russians switched on huge searchlights to illuminate the assault. The Germans, unsurprisingly, opened furious fire at the lights. “I shall never forgive Zhukov for that folly,” said Major Yury Ryakhovsky. “Everyone warned him what would happen, and begged him not to use the lights. But he kept saying stubbornly again and again: ‘I have told Stalin that we shall use them.’ ” The searchlights were manned by women. Ryakhovsky looked in revulsion upon the crews’ mangled bodies as they lay around the searchlight mountings.

Only the privileged among the men making the assault crossing possessed boats. The rest were expected to fend for themselves. Most crossed the wintry river, on which great chunks of broken ice still drifted, on primitive rafts. Lieutenant Vasily Filimonenko, an artillery forward observation officer, paddled across near Seelow with his five-man signals team clinging to a precarious wooden contraption contrived from doors and fence posts. “I never thought I’d make it,” said the gunner. His party was close to foundering when some engineers in a boat took them in tow. Intense German fire was whipping over the water. Flares and flames lit up the darkness. The ruins of shattered boats were drifting everywhere. Mortar and artillery rounds were falling among sappers struggling to build a bridge. Filimonenko saw one section of pontoons blasted high into the air by a direct hit. Yet the work went on. The gunner officer was in the water for half an hour before he crawled up the western bank shivering uncontrollably. He had lost one signaller wounded. They had managed to keep their sacred radio dry. They began to report the compass bearings of German muzzle-flashes back to their own guns.

It has been insufficiently recognized in the West that Zhukov’s assault across the Oder was a shambles. It was an operation worthy of the worst days of the Red Army, not of its final triumph. The Soviet archives bulge with after-action reports revealing the rage and frustration of many of those who took part, and who witnessed the reckless sacrifice of life. The preparatory bombardment fell largely upon forward positions evacuated by the Germans, and made little impression on their main defences. Many men who had fought at the Vistula crossing compared the effects of the Oder artillery preparation very unfavourably with the devastation achieved four months earlier. The Russian assault met accurate German artillery and mortar fire, especially from batteries at Frankfurt-on-Oder. There were violent complaints from the infantry about tanks lagging behind or becoming snarled in massive traffic jams behind the advance. A Sergeant Safronov reported seeing Soviet armour advancing over their own infantry positions, crushing men under the tracks. Captain Shimkov of the 68th Guards Brigade described how a mass of tanks and self-propelled guns became entangled in a gully, from which they shot blindly towards the enemy “because we had no experience of night firing. We were aiming by instinct.” Untrained replacements proved woefully incompetent—one unit reported three machine-guns jammed, because their Moldavian crews had no idea how to clear them. After the battle, political officers compiled an unedifying list of officers deemed to have behaved with cowardice or incompetence.

Worst of all, some Soviet minefields had not been properly cleared by the engineers. Hundreds of men died before they had even advanced beyond their own positions. Eight out of the 89th Regiment’s twenty-two tanks were wrecked on Russian mines. The 347th Infantry Division alone lost thirty men killed. A subsequent report declared furiously: “The divisional engineer Lieutenant- Colonel Lomov, a Party Member, and a brigade commander, Colonel Lebedev, also a Party Member, were too busy drinking before the attack to do their jobs properly. Colonel Lomov was too drunk even to report to the divisional commander.” It was in the light of behaviour such as this that Zhukov issued an order on 17 April cancelling the issue of vodka to several formations until further notice.

As daylight grew on the western bank, a pall of dust and smoke hung over the blasted German defences. Flocks of displaced birds wheeled in the sky. Men strove to save their eardrums amid the relentless thunder of the bombardment, now ranging on targets deeper into the German positions. Zhukov’s initial optimism at the success of the crossing was replaced by dismay, as his forces battered in vain at the enemy’s main line. “The further we got, the tougher the resistance became,” said Vasily Filimonenko. The strongest German defences, on the Seelow Heights, lay well beyond the reach of the Russians’ preliminary bombardment. Even after Zhukov’s men had secured bridgeheads, established their pontoons and pushed the first tanks forward, they found themselves making little progress. They struggled in the German minefields, for the Red Army was chronically short of mine detectors. The ground was miserably soft and treacherous for armoured vehicles, which bogged down in scores. The defenders were resolute. Zhukov found himself engaged in the most bitter fighting his armies had known since 1943.

O

N THE AFTERNOON

of 16 April, nineteen-year-old Helga Braunschweig, who worked in a Berlin telegraph office, was foraging for potatoes in the countryside east of Berlin with her friend Regina. The S-Bahn proved so badly damaged that they were obliged to abandon the train and walk. They were soon stopped at a military police roadblock, where the

Kettenhunden

said: “There’s nothing for you up that way, girls.” They wangled a lift in a truck up a side road and found themselves in Wehrmacht positions on a hill. They lingered to chat and flirt with the soldiers, even as they listened to the thunder of the guns and watched the relentless flashes in the distance as the afternoon light faded. The soldiers, summoned to action, hastily clambered into their trucks, gathering up the girls, and drove towards the Seelow Heights. Eventually they stopped, pointed the girls towards a house where they could buy potatoes, and left them in the road. Helga and her friend filled their bags, then lingered watching the horizon flickering with flame, gripped by a sense of disbelief. Berlin had been awaiting the Red Army for so long that, now it was coming, they could not grasp what it meant.

When at last they reached home, a cottage on the north-eastern outskirts of the city, Helga’s mother was almost prostrate with worry about their absence, but very grateful for the potatoes. The women stayed in the cottage through the days that followed, as a flood of refugees streamed westwards. Most of their neighbours left. An SS patrol asked why they were not fleeing: “Don’t you know that the Russians are raping all German women?” Helga’s mother shrugged: “That’s just Goebbels’ propaganda.” Her daughter said: “We simply didn’t know about what had been happening in the east.” Her boyfriend Wolfgang, a Luftwaffe wireless-operator, had contrived his own deft exit from the war by persuading the crew of his aircraft on a sortie one day to divert their course to Sweden, where they were interned, and Wolfgang later married a Swedish girl. Her father was a prisoner of the British. Like every Berliner, she had found the experience of the air raids terrifying and deeply debilitating. Now, perversely and naively, as the Russians advanced she felt: “Thank God they’re coming at last. All this will soon be over.”

B

Y THE AFTERNOON

of 16 April, Stalin was displaying audible impatience with Zhukov’s progress. “So you’ve underestimated the enemy on the Berlin axis,” he said irritably, when the marshal reported by telephone. “Things are going better for Konev.” The 1st Ukrainian Front had pushed ahead from its bridgeheads and was now swinging north towards the German capital. Zhukov reacted to Stalin’s jibes with characteristic ruthlessness. He ordered formation commanders personally to lead the attacks on the Seelow defences, and warned that further failures would be rewarded with instant dismissal. He took the drastic step of committing armoured divisions even before his infantry had achieved a breakthrough. There was no tactical subtlety here, no signs of a great captain manoeuvring forces with imagination. This was merely a clumsy battering ram, thrusting repeatedly and at fearsome cost against the German defences, as Zhukov vented his own frustrations in the lives of his men. “The worst performances have been those of Sixty-ninth Army, First and Second Guards Tank Armies,” he declared furiously, in a circular to all commanders. “These forces possess colossal strength, yet for two days have been fighting unskilfully and indecisively. Army commanders are not watching what is going on—they are skulking six miles behind the front.” He ordered that all army commanders should move their command posts to corps headquarters, and likewise that every corps commander should now direct operations from a divisional or brigade HQ. “Any commander who shows himself unable to fulfil his task will be replaced by an abler and braver man,” railed the marshal on 18 April. “Tanks and infantry cannot expect the artillery to kill all the Germans! Show no mercy. Keep moving day and night!” The commander of Ninth Guards Tank Army was lacerated for weakness, formally reprimanded and told: “By nightfall on 19 April, you will secure the Freudenberg area at any cost.”

The egos of two ferociously ambitious marshals were committed. They were taunted and goaded to a frenzy of rivalry by their master in Moscow, ever willing to exploit any human frailty to achieve his purposes. Whatever is said of Montgomery’s vanity, he would never have killed men to satisfy it. On the outskirts of Berlin, however, Russians were dying in their thousands to satisfy an urgency that was not tactical but entirely vainglorious. Zhukov dispatched some patrols not to find Germans but to discover how far Konev’s men had got. Konev, in his turn, incited his tank leaders: “Marshal Zhukov’s troops are now within six miles of the eastern outskirts of Berlin. I order you to be the first to break into the city tonight!”

Russian dead lay heaped in front of the defences, in a fashion that echoed the worst horrors of the earlier world war. Wounded men were untended for hours on the battlefield, as the scanty Soviet medical services were overwhelmed. The dead lay unburied for days. Zhukov’s headquarters ordered prisoners and civilians to be conscripted to remove them, lest epidemic disease be added to the horrors of battle. There were repeated friendly-fire incidents, as Soviet aircraft attacked or shelled their own units in the confusion. This difficulty was soon to worsen, as artillery fire from Konev’s and Zhukov’s armies began to cross the other’s lines. Command and control faltered and even broke down, as Soviet commanders lost sight of their own men.