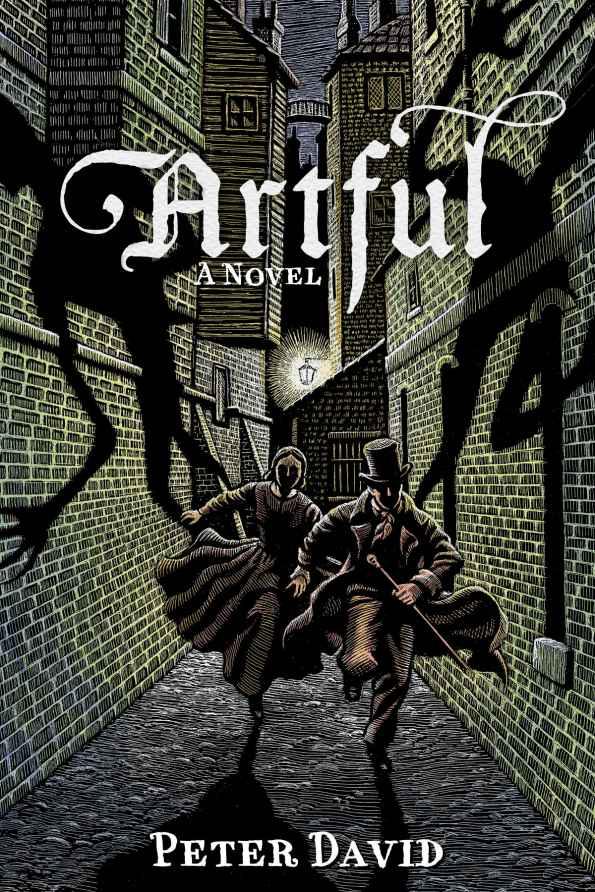

Artful: A Novel

Authors: Peter David

ALSO BY PETER DAVID

Published by Crazy 8 Books

Darkness of the Light

Height of the Depths

The Camelot Papers

Pulling Up Stakes

Fearless

Published by Random House

Tigerheart

Published by Pocket Books

Sir Apropos of Nothing

Woad to Wuin

Tong Lashing

Star Trek: New Frontier series

Imzadi

Published by Ace Books

Knight Life

One Knight Only

Fall of Knight

Howling Mad

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2014 by Second Age, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by 47North, Seattle

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and 47North are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

ISBN-13: 9781477823163

ISBN-10: 1477823166

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013958006

Cover design by becker & mayer!

Illustrated by Douglas Smith

To Charles

CONTENTS

AUTHOR’S PREFACE

W

HICH

R

EINTRODUCES

U

S TO THE

A

CCLAIMED

M

R

. J

ACK

D

AWKINS

, K

NOWN TO

S

UNDRY AS THE

A

RTFUL

D

ODGER

,

AND

L

AMENTS THE

I

NATTENTION

P

AID

H

IM AS

C

OMPARED TO

M

ORE

S

IMPERING

E

XAMPLES OF THE

D

AY

I

t has been an inordinate amount of time since Jack Dawkins was left in the dire straits as described by his previous biographer, the acclaimed Mr. Dickens, who, for all the right and proper praise heaped on him, nevertheless seemed to have his priorities ever so slightly out of whack in his previous visitation with Mr. Dawkins, described and referred to by various and sundry as the Artful Dodger, or Dodger, or the Artful, depending upon your familiarity with, and respect for, the personage

in question.

This is a rather shocking lapse in an otherwise laudable writing career that spanned two score of years in the first half of the nineteenth century. Mr. Dickens, a.k.a. Boz, received an understandable amount of acclaim for a career that included a variety of tomes of uplifting tales typically detailing the lives of people facing overwhelming odds in a society that seemed bound and determined to destroy them. More often than not, they

ended

up having their spirits crushed right before their lives were ruthlessly snatched from whatever was left of their battered and

broken

bodies

. They were the sort of tales, in short, that could only prompt readers to rejoice in whatever minor travails afflicted their own meager existences, as whatever it was they were facing paled to insignificance in comparison to the relentless onslaught of misery and mayhem visited upon many of Mr. Dickens’s cast of orphans, thieves, hapless fools, and misanthropes.

Standing upon the shoulders of many of these, however, remains Dodger, the renowned snatcher of handkerchiefs, purses, snuffboxes, and the like.

Why Mr. Dickens, in his biography of that particular moment, preferred to focus on the adventures of the orphan parish child, Oliver Twist, remains a matter of speculation and mystery to all subsequent scribes of those long-departed times: of a

London

nearly two centuries gone, back when it was a pox-

infested,

grimy, depressing, fog-bound, class-favoring, sprawling, noxious, odorous, and overall distasteful place in which to live and breathe and sicken and die—as opposed to modern times, wherein the pox has been largely attended to; so that’s progress of a sort.

This is not to be uncharitable to Master Twist, who knew little enough charity in the first decade or so of his young life. Nor do we wish to detract from the eventual happy turn that his fortunes took. Nevertheless, the more unkind observer (which we would like to think that we are not . . . but which our actions would lead us to believe we are) would have to make note of the fact that

Master

Twist spent an ungodly amount of his time on the page weeping for some reason or other. Whatever circumstance confronted him, his default reaction was to burst into tears, which makes him seem to us—not with the intention of disparaging the fairer sex, but still—a bit womanish. This famed orphan of the storm tended to bob about as helplessly as a cork (embracing the cliché in order to maintain the metaphor) until matters happened to, through no effort of his own, land him upon safe and welcoming shores.

Contrast him to the Artful, who, when last Mr. Dickens graced us with his presence, was seen standing in a London courthouse, having been accused of snatching a silver

snuffbox

out of the pocket of some individual who no doubt needed it far less than the Artful. Indeed, it should be noted that so formidable an

individual

was Dodger that the circumstances of his being apprehended by the authorities was not even witnessed by the reader of Master Twist’s “adventures.” Instead, they were described in tragic detail by Master Charley Bates, or, as he was frequently referred to with equal tragedy, Master Bates (that is to say, Master Bates recounted it after the fact, and Mr. Dickens dutifully reported it). Faced with a pompous judge, the Artful Dodger disdained to defend himself or his actions, loudly declaring that this was not the shop for justice and that his lawyer would certainly attend to the scoundrels inconveniencing the Artful directly if he were not currently breakfasting with the vice president of the House of Commons. It was a performance of sheerest bravado that would have made lesser men leap to their feet and applaud—as opposed to the greater men, who merely scowled and declared that the formidable Artful was to be transported forthwith to the untamed and thoroughly criminal continent of Australia. Imagine, if you will, Oliver Twist in the same predicament. There is little doubt that his defense would have been to fall to his knees, sobbing and lamenting his lot in life, a performance that would unquestionably have united lesser and greater men to shunt the little whiner off the English Isles and into the Atlantic as expeditiously as possible, conceivably without benefit of boat.

Indeed, if pictures are worth a thousand words (and admittedly we have already consumed nearly nine hundred words) then one not need think beyond the classic renderings of the two gentlemen in question. Conjure Oliver Twist in your mind, and you will doubtless envision him looking upward in a pathetic, supplicating manner, holding up his empty bowl of gruel and uttering the immortal words, “Please, sir, I want some more.” Hardly a defiant, brazen challenge to

authority

. And while Master Twist’s defenders will point to this moment as a transformative one in which the young hero asks for more

because

he can stomach no further dismissive treatment, I will simply say this:

Untrue.

He asked for seconds because he drew the short straw, taken as a consequence of a bully in the workhouse demanding that someone bring him a second helping lest the starved older boy wind up consuming his bunkmate . . . and the boys took this threat seriously. Not quite an act of derring-do, then. (Although even we, skeptics of Master Twist’s rightful place in the pantheon of heroes, will indeed applaud politely for his subsequent assault on a noxious older lad who spoke disparagingly of Oliver’s mother. Then again, there are lines that even the most whimpering of boys will not see crossed.)

So there is the classic image of young Oliver in your mind’s eye: a failed beggar with an empty bowl. Now set next to it your mental picture of the Artful Dodger, described by Mr. Dickens thusly:

He was a snub-nosed, flat-browed, common-faced boy enough, and as dirty a juvenile as one would wish to see; but he had about him all the airs and manners of a man. He was short of his age with rather bow-legs and little, sharp, ugly eyes. His hat was stuck on the top of his head so lightly that it threatened to fall off every moment and should have done so, very often, if the wearer had not had a knack of every now and then giving his head a sudden twitch, which brought it back to its old place again. He wore a man’s coat, which reached nearly to his heels. He had turned the cuffs back, halfway up his arm, to get his hands out of the sleeves: apparently with the ultimate view of thrusting them into the pockets of his corduroy trousers; for there he kept them. He was, altogether, as roystering and swaggering a young gentleman as ever stood four feet six, or something less, in his bluchers.

Two questions immediately come to mind. The first, of course, concerns the definitions of “roystering” and “bluchers.” The former means “blustering,” and the latter are half-boots, typically of leather, so that puzzle is easily attended to.

Of greater curiosity is this: Why did the adventures of such a memorably described, thoroughly engaging, and far more captivatingly visualized young man—always pictured with a cocky smile and upraised, mocking eyebrow rather than tears of pathos trickling down his face—play second fiddle in the great orchestra of fiction to the perpetually sobbing Master Twist?

The answer is profoundly deep and disturbing and involves something that most normal people would find deeply impossible to accept.

What is that thing?

Vampires. Or, as it was spelled at the time,

vampyres

.

Yes, we know: It is difficult to accept, a strain to wrap your head around. Go and take the time to do so. Watch some television programs, or read some books in which vampyres are heroic and charming and sparkle in the daylight, and then return here and brace yourself for a return to a time that vampyres were things that went bump in the night.

It is our speculation that Mr. Dickens, despite his having taken up the unsavory profession of writer, nevertheless considered himself a gentleman, and there were some aspects of life that gentlemen simply did not wish to address. As such, he might have constrained himself to the rather mundane story about a boy nam

ed Twist, if only to pay respect to the

delicate

social mores of his time regarding all things truly

detestable

, such as politicians or, as is the case of Dodger’s full history, vamp

yres. For that matter, it was entirely possible that he simply did not wish to alarm the citizenry of London and its surroundings with the knowledge that vampyres lurked within their midst. It was tragic enough for the average citizen to know that bloodsucking monsters known as tax collectors

already

existed

; to be informed that there were

other

inhuman bloodsuckers stalking the night as well, desiring to sink their fangs elsewhere than bank accounts, might simply have been too much for people to bear. It was one thing for Mr. Dickens to be able to acknowledge the existence of the supernatural, as he did in

A Christmas Carol

, for that could easily be seen as a fairy tale rather than the exacting biographical study that it was. (Indeed, had Scrooge possessed the Artful’s contacts and resources and used those to avail himself of the services of an exorcist, then the tale might well have concluded very differently for Scrooge, Tiny Tim, and the ill-fated Christmas goose.) But

Oliver Twist

was far too much of a genuine slice of life to allow the

unlife

to intrude, at least substantively.

Which is not to say that the original story does not

hint

of the existence of vampyres. Any conscientious reading of the text will make it plain. We will provide two examples for any who may doubt us, both of which will be particularly germane to the tale you are about to peruse.

First, though, it should be noted that in order to spare private citizens embarrassment, whether deserved or not, and very likely legal actions against himself for libel and slander, whether deserved or not, Mr. Dickens tended to assign whimsical and entirely descriptive fictitious names to his cast. So renowned for this was he that to describe a name as “Dickensian” is to say that it is aptly ironic. In other words, there is a truth to it that may well be obscure to the owner, but evident to observers.

Consider, then, young Oliver’s antagonist in Chapter XI of the original volume: a formidable, powerful, and utterly cruel police magistrate with the name of Mr. Fang. Let us dwell upon that name and evoke it yet again: Mr. Fang, who slunk through merely the one chapter of Mr. Dickens’s tale, but will be allowed to assume the full measure of his villainy in this recounting.

It staggers credulity to think that the name is a random happenstance. With a name like Mr. Fang, what else

could

the magistrate be

but

a vampyre? His subsequent dealings with Jack Dawkins, the Artful Dodger, who—as we will see in these pages—becomes inadvertently drawn into the web of Mr. Fang’s plots through an act of consideration while momentarily forgetting that no good deed goes unpunished, could not be ignored if one is to give a fair and accurate recounting of Dodger’s activities.

And then there is the matter of Fagin, routinely referred to as “the Jew.” I needn’t remind you that this was back in the day when the mere act of not being a Christian was to make one suspect, if not an outright potential criminal. These, of course, are far more enlightened times, when it is only acceptable to believe that not being a Christian is likely to mean one is a criminal only if one is a Muslim (or at least so we’ve been assured by people who claim to know such things), and therefore we shall refer to Fagin merely by his surname.

This would be the selfsame Fagin who prefers to hide within the shadows and never faces the harsh light of day.

This would be the selfsame Fagin who is shown preparing food from time to time, but never consuming it.

The selfsame Fagin who sits in a commons house and, while others are drinking, is reading a magazine.

The selfsame Fagin who, when handed a glass of wine by the evil, but decidedly human, Bill Sikes, is described as putting it to his lips, drinks not from it, and then claims he has had a sufficient amount to quench his thirst.

So let us consider the name itself: A simple rearrangement of two letters provides “I Fang,” delineating a distinct connection to the other gentleman named Fang already extant in the book.

As for his clothing: all in black. A hat, broad brimmed to keep the damaging rays of the sun at bay, should he be unlucky enough to be dragged from the confines of his hidey-holes, as indeed happened in the course of the original novel.

And his physical description: “And as, absorbed in thought, he bit back his long black nails, he disclosed amongst his toothless gums a few such fangs as should have been a dog’s or rat’s.

”