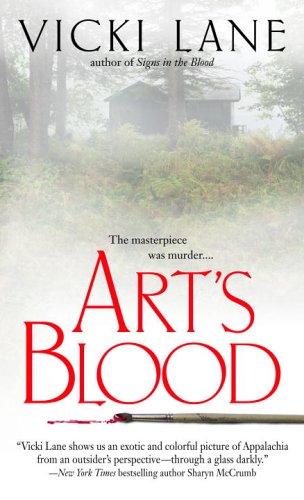

Art's Blood

Authors: Vicki Lane

O

F

LETA AND

J

OSIE, FOR ARTISTIC INSPIRATION,

J

OHN, FOR ALL THE POPCORN

I

T MAY NOT QUITE TAKE A VILLAGE TO PUBLISH A BOOK,

but it does take a lot of folks. These are some who have helped me along the way.

Kate Miciak always pushes me to do better. What a great editor! Ann Collette, my terrific agent, is a source of encouragement and funny e-mails. Jamie Warren Youll designed the beautiful covers for

Signs in the Blood

and

Art’s Blood.

Deborah Dwyer’s copyediting kept me straight. Thanks to Caitlin Alexander, Loyale Coles, and Katie Rudkin— all part of the team at Bantam Dell.

Thanks are due as well to Candace Aldridge Rice for creating and maintaining my Web site. Rachel Mosler gave me a glimpse into the life of a River District artist, and Sebastian Stuart helped with background tidbits about Boston. Victoria Baker showed me around her beautiful herb and flower farm and told me about the business of growing herbs and flowers. Thanks to Karol Kavaya for proofreading again.

Many thanks to the Bag Ladies of Waynesville, North Carolina, for astute comments re Phillip Hawkins, and to Dr. Marianna Daly, Kimberly Bell O’Day, and Christie Hughes for advice about poisons.

Note:

The twice-yearly studio strolls in Asheville’s River District take place in June and November, not in September.

Art’s Blood

is, after all, fiction….

The following books were useful to me:

The Proper Bostonians

by Cleveland Amory (E.P. Dutton & Co., New York, 1947);

Jane Hicks Gentry: A Singer Among Singers

by Betty N. Smith (The University Press of Kentucky, 1998); and

Gift from the Hills: Miss Lucy Morgan’s Story of her unique Penland School

by Lucy Morgan with Legette Blythe (The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., New York, 1958).

I still see the bed— its wide white expanse floating like a snowy island on the deep pearly carpet— the creamy tufted silk coverlet neatly folded back— the soft heaped pillows, their pale lace soaked and stiff with her blood. Even the smells come back to me— Chanel No. 22, that sweet, springlike fragrance she always wore— the scent of the white roses on the nightstand— and something else— a harsh, ugly,

insistent

smell— cloying and faintly metallic. And after all these years I still see her satin slippers beside the bed, placed neatly parallel to await a morning that never came— and the shadowy marks of her heels on the linings almost too much to bear.

On that day and until the day we buried her, he had seemed broken— weeping and bewildered, letting himself display a weakness none would have imagined. Was it genuine sorrow, I wonder now, or only a charade, as subsequent revelations would seem to suggest? And the child— so beautiful, so like her mother that it broke my heart to look at her— the child remained dry-eyed and quiet— already, I see now, beginning the long retreat that has transformed her into what she is today. And these are the scenes, the faces that haunt my nights.

I have noted, as the years go by, that I seem to require less and less sleep. But recently the dreams have been so persistent— I awake each morning haggard and weary, and at the end of the day, the bed is no longer a comfortable refuge but a loathsome penance. I approach it, in the words of Bryant’s “Thanatopsis,” “like the quarry-slave at night, / Scourged to his dungeon.”

My faithful Reba was aware of these tormented nights almost before I had allowed myself to see the pattern forming. At first she was content to dose me with her chamomile or catnip tea at bedtime, but when these had little effect on the dreams, she nagged at me until I agreed to see Dr. P. Not a usual thing for her, as Reba generally puts her faith in herbal nostrums and her supposed healing powers as seventh daughter of a seventh daughter. Remarkable, to find the old beliefs still so strong in this new century. I’m certain that the imaginations of my Biltmore Forest neighbors would be titillated by the news that Lily Gordon’s housekeeper is a self-proclaimed “witchy-woman.” What a delicate morsel of fresh gossip for their cocktail hour now that the years have leached the juice from the old scandals.

After a second week of troubled nights, my witchy-woman conceded defeat. Miss Lily, you ain’t doin no good, she pronounced in her flat mountain voice, stripping the rumpled sheets from my bed with her usual brisk efficiency. Woman your age, you need your sleep. You kin fire me if you want to but I’m callin that doctor of yourn. We’ll see what he says about all this dreamin.

And after a consultation and the usual tedious rounds of inconclusive tests, it was at Dr. P’s suggestion that I began this journal. There’s no obvious physical explanation for your disturbed nights, he said, tapping the sheaf of papers on the desk before him. I could write you a prescription that would ensure sleep, even dreamless sleep— but I’d rather you try something else first. The fewer medications, the better, is my opinion. He reached into a drawer, pulled out a slim, blue-covered book, and offered it to me.

It’s a diary, he said, looking a little sheepish as I raised my eyebrows. I want you to record everything that keeps you awake— doubts, fears, even confessions. We all have our sins of omission as well as commission. If something troubles you, write it down. No one will ever read your journal; I want you to do it for yourself alone. Just write everything down and then let it go, he said. Burn the pages as soon as you finish them, if you like. I smiled grimly as I took the little book from him. A woman of my age had best keep the matches near to hand, I told him.

Dr. P patted my shoulder in that irritatingly patronizing manner of his and called me a wonder. With all you’ve weathered, he said, it’s not surprising that you have bad dreams. He explained, as if to a child, that dreams are often caused by the mind’s sifting through matters inadequately resolved in the waking hours— experiences, thoughts, emotions too unpleasant to be dealt with and so, repressed. Earlier, P had the effrontery to suggest that I see a psychiatrist, to work through some of these

issues,

as he called them, but I dismissed that idea as preposterous. And thus he proposed the journal.

If only you were a Roman Catholic, he chuckled. There’s much to be said for a routine examination of conscience followed by confession and absolution. Clears the mind, so to speak. Many people blame themselves for trivialities when they’ve lost someone. They think, If only I’d done this or hadn’t done that…He helped me up and walked with me to the door where Buckley was waiting. P is a fool in many ways— there are things I would never speak of, even to a priest. But P could be right in this instance. Perhaps putting these memories down on paper, giving them a shape, however ephemeral ( for I do intend to burn these pages), will help me to a less troubled sleep.

So now I have my journal to keep me company through the interminable afternoons— the quiet, tedious hours when the tick of the clock in the hall seems to slow and hang suspended like a dust mote in the fading light— the light that dims inexorably, as if in rehearsal for the long night which creeps closer with every heartbeat, like the fog rolling in across the harbor in my childhood. In these times, as I drowse in my chair, the pen slipping from my fingers, the past is present, the dead still live. And it is at these times that I see F as she was then, my mountain flower, my heart, my soul.

F

ROM HER VANTAGE POINT AT THE TOP OF THE STEPS

leading into the gallery, Elizabeth Goodweather regarded the pile of burnt matchsticks with an expression that wavered between hilarity and disbelief. The heap of pale wooden slivers, some charred just slightly at one end, others little more than a fragile curl of carbon, sat in the exact middle of the room on a low pedestal covered with a sheet of thick red vinyl. The

assemblage

was about four feet in diameter and its peak was knee high. And growing.

The stark bone-white walls of the gallery had been covered with a fine grid of narrow scarlet-lacquered shelves bearing red and blue boxes of kitchen matches in uniform rows. As Elizabeth watched, one after another of the dinner-jacketed and evening-gowned throng of art patrons took boxes from the wall and began striking matches, extinguishing them, and adding them to the charred accumulation that was the focus of the evening’s event.

Seemingly all of Asheville “society” had turned out to mark the late August opening of the Gordon Annex: a long-awaited and costly addition to the Asheville Museum of Art. It was the munificent gift of a single benefactor— Lily Gordon. This elegant little woman—“somewhere in her nineties,” whispered a woman to Elizabeth’s left— had cut the crimson ribbon that stretched across the entrance to the annex and had spoken a few brief words in a voice that, though slightly cracked with age, was clear and carrying. Her spare frame was upright, conceding not an inch to age. Now she sat in a comfortable chair with the museum’s director crouched by her side and the chairman of the board leaning down to catch her words.

The old woman wore a simple but beautifully cut evening dress of black satin accented with white—“vintage Chanel,” Elizabeth’s neighbor had informed a friend— and her arthritic fingers were covered with rings that glittered as she reached up to accept a glass of champagne from the chairman of the board. Behind her chair stood a tough-looking, gray-haired man in a dark blue suit. His craggy face was expressionless and his eyes scanned the throng without stopping.

More like a secret service agent than an art lover,

Elizabeth decided.

Fascinated, she studied the little group, wondering what this very old woman made of the scene unfolding before her apparently amused gaze. “She’s always been the museum’s greatest patron,” someone behind Elizabeth murmured, “absolutely millions of dollars. Her house is literally crammed with art— Picasso, Kandinsky, Pollock— just to name a few. She and her husband began collecting just after World War II. Of course…”

The voice moved away and Elizabeth smiled, wondering if she looked as out of place as she felt in this rarefied crowd.

“You

are

coming in for the opening of the Gordon Annex at the museum, aren’t you?” Her younger daughter Laurel, on a visit out to the farm a few days earlier, had fixed her with a demanding eye. “It’s this coming Saturday.”

“Ah,” Elizabeth had hedged, “Saturday…Well, I…”

“Mum,

this is a really important show! And you

know

the artists— Kyra and Boz and Aidan. They’re just across the hard road which makes them neighbors. So the least you can do…”

As an aspiring artist herself, Laurel was very much a part of the burgeoning art scene in Asheville and had done her best to develop Elizabeth’s appreciation for the latest trends. Last year Laurel’s passion had been outsider art; this year, performance art was evidently the next new thing. Although she supported herself with a job tending bar at an upscale restaurant, Laurel devoted most of her free time to constructing vast mixed-media “pieces,” as Elizabeth had learned to call them. Recently, however, Laurel had begun to speak wistfully about the “ephemeral beauty” of performance art and of the “spiritual purity” of a carefully choreographed presentation that would never be repeated.

Laurel had been relentless. “It’s going to be something really special— the people attending the show will participate in the creation—” She had broken off, seeing Elizabeth’s face, which unmistakably said,

Oh, great.

“— if they choose to, I mean. And then Kyra and Boz and Aidan will be taking pictures during the piece and next month there’ll be a show at the QuerY to display the photographs.

And—”

she continued, with the air of someone producing a trump card, “there’s going to be a really

awesome

twist to the whole thing that I can’t tell you about now but it’s going to generate some

incredible

publicity for those guys.”

Elizabeth had, without enthusiasm, agreed to meet Laurel at the Saturday night opening. Kyra and Boz and Aidan

were

neighbors and one did for neighbors whenever possible.

Even if it means going to some ridiculous performance and dressing up for it— evening clothes, my god!

Elizabeth had fumed, rummaging in her closet for something to wear. At last she found a long black skirt of heavy polished cotton that she had worn to some forgotten event, and a white silk shirt still in its gift box, a Christmas present from her sister two— or was it three?— years past. A narrow jewel-toned scarf, discovered crammed in the back of a drawer of socks and underwear, would work as a cummerbund. Suddenly her mood had improved.

They’re just kids, after all. To have a show at the Museum of Art is a big deal for Kyra and Boz and Aidan.