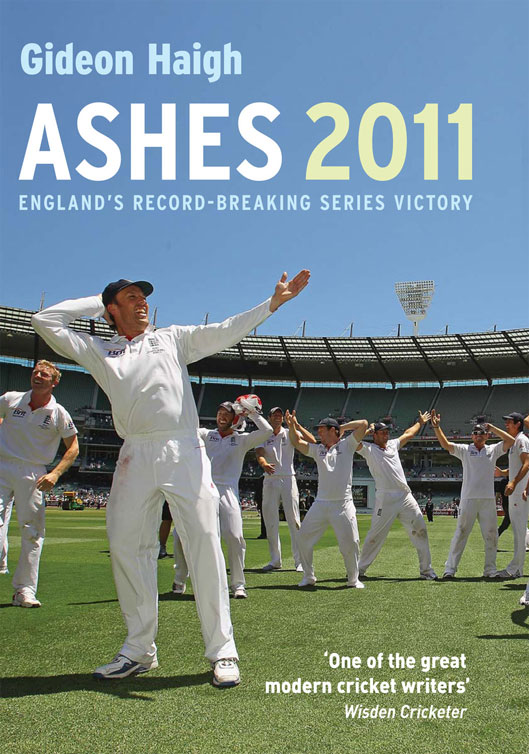

Ashes 2011

Authors: Gideon Haigh

Introduction

In the southern summer of 2010–11, England retained the Ashes in Australia 3–1. The novelty hasn't yet worn off that statement, and it might be a while before it does. Had you envisaged such a prospect this time four years ago, you would have been laughed out of whatever hostelry you proposed it in – because you would have needed a few drinks to work up the bravado to say it. At the time, England had been on the receiving end of the most thorough defeat in Test history. Australia faced a wave of retirements, but they had regenerated before, and were backing themselves to do so again.

The Ashes of 2009 were then played out by two battling, middling, sometimes shambling teams. But for the improbable resilience with the bat of James Anderson and Monty Panesar at Cardiff, Australia might have retained the trophy; as it is, an unlucky coin toss and poor selection cost them dearly at the Oval. In their summer of 2009–10, however, Australia won five of six Tests, a good summer's work even by the standards of their primrose path of the late nineties and early noughties. There was much talk of new fighting spirit, new talent like Steve Smith and Phil Hughes, new characters like Doug Bollinger and Ryan Harris. If not the magnificos of yesteryear, the Australia team still had a winning feeling about it, consolidated when they comfortably bested New Zealand in that country at summer's end.

What Masaryk said of dictators, then, can also be said to apply to cricket dynasties: they always look good until the last minutes. Because cracks appeared when Australia went to England in the middle of 2010 to play Tests against Pakistan and one-day internationals against England; these were then widened by Tests in India and finally by one-day internationals against Sri Lanka at home. On the first day of the Ashes, an Australian bowler took a hat-trick; by the end, Australia had for the first time in the country's cricket history lost three Test matches by an innings. Had I not been there as eyewitness, I'd hardly have believed it; but I was, and the result is in your hands.

This book is a collection of my despatches. It interleaves the daily match reports I wrote for

Business Spectator,

and the daily columns I composed for

The Times.

They are unaltered from the form in which they were sent, so you can see when my forecasts were awry, often enough, as well as right, just occasionally, albeit probably by accident. Players don't have the luck of magisterial hindsight, rewriting events to leave out the bad shots they played, the long-hops they served up, the catches they dropped; it's fairest to be read in parallel. And let's face it: if you were right all along, where would be the point in watching?

One observation, however, may be pertinent. Reporting and analysing Test matches is both satisfying and deeply challenging, rather like trying to review a play at the end of each act, except from a distance of maybe a hundred metres, with little idea how the characters will appear and reappear, and no notion how the plot will unfold. With the online news environment having created a demand for round-the-clock content, both my report and my columns had to be filed within an hour of stumps, barely time to squeeze in the nightly press conference where a player from each side said not much about very little. I enjoy deadlines, and seeing something I have written posted within minutes of my completing it retains for me a heady novelty. Yet so heavily does the accent now fall on instantaneous judgement that the scope for considered journalism cannot but dwindle, with an impact on the way that cricket is perceived, understood and interpreted.

Caveat lector.

This was a tough tour from a personal point of view also, given the separations from my wife Charlotte and one-year-old daughter Cecilia, for which even the wonders of Skype could not make up. I finally had them with me in Sydney, which meant that I ended the Test with my head ringing from both Barmy Army chants and songs from

In The Night Garden,

idly transposing Mitchell Johnson and Makka Pakka. In doing so I obtained a better understanding of what it takes for a cricketer to leave home and hearth for a foreign clime. If Andrew Strauss's tourists missed their loved ones half as much as I missed mine, they have my deepest sympathy.

It remains for me to thank my editors, Tim Hallissey at

The Times

and James Kirby at

Business Spectator,

for the opportunity to cover this constantly fun and fascinating series. I'd also like to acknowledge my estimable colleagues at

The Times

– Simon Barnes, Richard Hobson, Geoffrey Dean and especially the chief cricket correspondent Michael Atherton – for being a team scarcely less cohesive than England. I look forward to working with them all again.

GIDEON HAIGH

January 2011

KINDLING THE ASHES

5 OCTOBER 2010

THE ASHES

Folie à Deux

The wife of Australia's longestâserving prime minister, Robert Menzies, saw two days of Ashes cricket, at Melbourne and Lord's, separated by eighteen months. On the first occasion, England's Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe batted all day; at the beginning of the second, she was bemused to see Hobbs and Sutcliffe again coming out to bat. 'Well, I never,' she said. 'Don't tell me those two are still in?'

Good story â it also contains a kernel of truth. For those who don't understand it, but also for those who do, the Ashes is like one long, apparently unending, constantly fluctuating, seemingly unresolvable game â cricket's ultimate, insofar as even when a series is won or lost, that ascendancy is provisional until the resumption of competition. It never ends with 'goodbye', always with 'check ya later'.

And that it also is: a check. No matter where the two countries stand in cricket in other respects, Australia and England exhibit a perennial desire to ascertain where they rate in relation to one another. World Twenty20? A useful bookend. World Cup? Handy for keeping your cufflinks in. But on the national mantelpiece, England and Australia keep space permanently cleared for the Ashes, even if there have been spells like the 1940s and 1990s when that area in England has grown a mite dusty.

There is something marvellous about this; also something quite mysterious. The Ashes is cricket's Stonehenge. Its origins are obscure. It was standing when we got here, and will outlast us all. Having outgrown its original purpose, its reason for being is not always entirely clear. Yet it goes from strength to strength, attracting more pilgrims than ever.

It is Test cricket's definitive rivalry, not because it has always provided cricket of the best quality, but because of two aspects integral to it. Firstly, continuity: since England came round to the fiveâTest format in 1899, it has been decided over a shorter distance on only a handful of occasions. Secondly, conduct: it is rough, tough, even sometimes bitter on the field. 'Test cricket is not a lightâhearted business,' warned Sir Donald Bradman. 'Especially that between England and Australia.' Yet off the field, it has remained, with occasional exceptions that prove the rule, remarkably civil and companionable.

Not every English visitor finds Australia to their taste. 'Dear Father,' one of Douglas Jardine's team wrote home in 1932â33, 'this country is just hundreds and hundreds of miles of damn all, and then hundreds of miles more of it.' But the long distances and long durations involved in Ashes cricket beget hospitality: Alec Bedser and Arthur Morris played a decade's cricket against one another, then spent another five decades as friends and guests in one another's homes.

To the Ashes, there is also a pleasing equilibrium. Although their countrymen sometimes like to pretend otherwise, no two competitors in international cricket have as much common cultural ground: of language, history, institutions and even sporting values. The differences stand out the more for those surrounding similarities.

The conditions for cricket, for example, are radically dissimilar, and geography and meteorology have been hugely influential in the last five years: heat, harsh light and flat wickets in Australia, cloud cover and juice in England. And while globalisation should by rights be taking the edge off some of the distinctions between Australian and English cricketers, it's not doing so quickly. Ricky Ponting could be from no other country; Andrew Strauss likewise. Mitchell Johnson bounces it like an Australian; Jimmy Anderson swings it like an Englishman. From time to time, Australia and England eye one another with envious appreciation. Australians returned from England in 2005 wishing they had their own Andrew Flintoff; English spectators at the Oval Test of that series serenaded Shane Warne with a chorus of: 'We wish you were English'. But the fans of each country have ideas of the qualities in a cricketer they esteem.

What has changed about the rivalry? It originates, of course, from English colonisation of the Australian continent and from the desire to test the prowess of one society against the other. Sport, offering results in a fixed time on a superficially even footing, was an ideal medium for patriotic expression. 'Read the accounts of ⦠the cricket matches,' opined Marcus Clarke in

The Future Australian Race

during the year of the inaugural Test match, 'and say if our youth is not manly.'

We sometimes think of this as all one way; that it was always Australians seeking an estimation of themselves against the imperial power. We should not underestimate how much the English enjoyed the challenge. The British historian David Cannadine has pointed out that the late Victorian age was one in which traditional power structures sensed menace from forces of equalisation â industrialisation, urbanisation, extensions of the franchise. Reminding an uppity colony who was in charge was therapeutic for the English too.