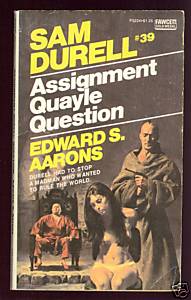

Assignment - Quayle Question

Read Assignment - Quayle Question Online

Authors: Edward S. Aarons

VIRGINIA

Chapter One

Up here, on the high wooded slope that overlooked the narrow flanges of the valley, the wind had a cool autumnal bite to it. Durell shivered slightly. He flexed his fingers to keep them warm, concerned about the effect the temperature change might have on the trigger spring. The wind that funneled down the north-south orientation of the Alleghenies had to be considered for trajectory deflection. He knew he would have only the one chance. He had to make it perfect, against the light of the sun in the west, where it just touched the long whale-back ridge opposite them on the other side of the valley.

“Marcus? Henley?”

“Yo,” they both said.

Franklin said, “This ought to be good enough.”

“A little more to the north,” Durell said. “Marcus, take Henley down there with you. Get close to the road. Be ready when you hear them coming.”

The men in their hunting shirts and heavy boots all nodded. They looked competent. Durell hoped the reports on them from DIA were accurate. He wasn’t too worried about the first two. It was Franklin who worried him.

Franklin, puffing a little, said, “We can spot him perfectly from here, Cajun.”

“It’s not good enough. Over there, where the spur pushes west, toward the bridge. We have to get higher.” “I’m tired,” Franklin objected. “We’ve hiked over the

ridge three miles from the van.” He was a little too stout for this sort of work.

“We’ll go higher,” Durell insisted. He thumbed the button on his transceiver. “Dee?”

“Yes, Sam,” she answered quietly.

“Any problems?”

“I’m ready to go on down to the spa.”

“Take the road that comes around to the back. In that hippie van, they’ll never let you stop at the front gate.”

“All right, Sam. Sam?”

“Yes.”

“You be careful.”

“Yes.”

“You read the dossier on Tomash’ta.”

“We’ve all read it.” He was a little irritated. “Just make sure the target is where he’s supposed to be. And his family.”

“Right, Sam.”

Her voice flowed through him, calm and soft and competent. Deirdre Padgett would be moving the gear now, handling the van that the lab boys had picked up, all decorated with wild primary colors in sworls of red and yellow, artfully rusted, curtained with ragged chintzy stuff. There were other vans of this type, parked here and there in the national forest. It wouldn’t be noticed. Neither would she, in her patched denims and tie-dyed loose shirt that could not conceal the long, clean lines of the body he knew so intimately. Durell did not want to work on this one with her. Kokui Tomash’ta was too dangerous, too tricky, too fast. But McFee hadn’t given him a choice.

He let Franklin catch his breath while Marcus and Henley faded downhill toward the cut where the road came through the notch in the hills. It took less than ten minutes.

“All right,” he told Franklin. “Let’s go.”

“They aren’t there yet.”

“Yes. Over there,” Durell said.

“Where?”

“Near that yellow maple. Half a mile north-northeast.”

“The sun’s in my eyes.” Franklin squinted against the high light. “I can’t see a damn thing over there.”

“Don’t worry about it.” Durell saw that Franklin was breathing normally again, and stood up. The Remington .30-30 felt smooth and warm in his hand. There wasn’t too much time left before the autumn sunset plunged the narrow valley into dark gloom. The lights of the little village to the north, where the Alleghenies shouldered together to form another notch, would be of little help here. The snooper scope would be an aid, of course, if it grew dark before Tomash’ta tried to come through, but he hoped it would happen while it was still daylight. He wanted to get Tomash’ta quickly and cleanly, and finish it. He didn’t want to chance that someone else might kill him.

The mountains seemed to sing in the clear, crisp air of afternoon. The sky was a pale burnished blue, so pale it seemed white, except where the high cirrus clouds to the west reflected the red of the setting sun. The foliage, which had brought so many leaf-lookers to the Shenandoah, off to the east, had already passed its peak, although there were gaudy splashes of red, yellow, and bright purplish brown in the oaks, lower down in the valley. Traffic on the road was negligible, seen from the height of the pass through the southern notch to where the village at the northern end of the valley filled both sides of the narrow gap. Durell thought it should be relatively easy to pick out the sporty blue Porsche that Tomash’ta would be driving.

The right front tire would do it—when the car reached that spot down there, where there was a decent shoulder to the road. And Tomash’ta would try to save himself by taking the car there rather than crash on down into the gorge.

As if reading his mind, Franklin, the FBI man, puffed and said, “It would be just as easy to grease his skillet, Sam.”

“We will. But I want him to tell us a few things first.”

“He’s not apt to talk, anyway. He’s one of those fanat-

ics who call themselves the Japanese Red Army, one of those terrorists, like a kamikaze. He won’t talk.”

“You’re always a pessimist,” Durell said.

“And you’re not? You’re in the USA now, Cajun. Not in some African jungle or Asian village where you could really put the blocks to the bastard.”

“That’s not my line, anyway.”

“Just the same, we have laws here, Sam.

And

lawyers. Of which, God help me, I’m one.” Franklin, who had worked for the FBI for over ten years, and who considered Durell’s presence an intrusion into his own field of domestic security, winced at a vision of future court hearings, trials, appeals, more appeals, hostile judges, countercharges of brutality, violence, and failure to cede to the subject full latitude in protecting his Constitutional rights, even though Tomash’ta was an alien. Franklin didn’t care much for anything he had heard about K Section, that free-wheeling, trouble-shooting branch of the CIA that worked everywhere in the world. He didn’t know why Durell, a senior field agent for K Section, had been called here from Hong Kong or Karachi or some God-forsaken place like the Somali desert to take command of this operation. He admitted some resentment in himself.

If anything went wrong, it wouldn’t matter or carry any juridical weight that Kakui Tomash’ta was a known international assassin, a killer who operated for hire now for a splinter group of anarchists known as the Red Lotus. It all seemed like a lot of hash smoke to Franklin. What Tomash’ta was, or more correctly, was supposed to be, was not Franklin’s real business. Tomash’ta had committed no crimes here—as yet. He wasn’t even on the Interpol list. Ergo, you could watch and you could wait, but you couldn’t touch.

Durell didn’t think that way, he supposed. It was only by exceptional fiat and interdepartmental back-scratching that Durell was working on this within the borders of the United States. The man was more at home abroad, Franklin had been told. He was certainly different. He worried Franklin. There was a cold professionalism about Durell, a sense of careful isolation, which, while it might be comforting in some respects, certainly was disturbing in its unpredictability.

“Here,” Durell said.

They had climbed through blazing sumac and pale alders and then crossed a small plateau covered thickly with hazel bushes, screened from the valley floor by an old stone fence that meandered across the shoulder of the mountain. There was no sign of the farmhouse that once had existed here, before the land was taken over by the Federal Forest Preserve. Above them, the wind soughed through a thick grove of long-needled pines. The whiteness of the sky was being tinged now by lambent rays from the setting sun. The air felt colder.

“Yeah,” Franklin said. “I agree, this is better. I can see the bridge now.”

“That’s where we’ll take him.”

“What about Marcus and Henley?”

“If I miss, Marcus can make the hit.”

Franklin smiled without humor. “Do you think you will miss?”

“No,” Durell said.

He put the rifle down on the stone wall and blew on his hands to warm them.

If only the local cops stayed out of the picture long enough for them to pick Kakui Tomash’ta out of the wreckage and get him up here and away in the van. If only Tomash’ta came through here at all. If and if and if. The business was always full of permutations, combinations, and probabilities. Not to mention the impossibilities.

He wished his leave hadn’t been interrupted, and that he was back in Washington. Better still, in Prince John, on the shores of the Chesapeake, with Deirdre.

From the comer of his eye he saw a troop of quail move with cautious, silent tread out of the pine thicket. A squirrel leaped from an alder branch and scurried down into the scrub. He saw a deer trace to his left, where the stone wall was broken down, and heard the trickle of water somewhere in the distance.

They waited.

Down iii the valley, where the dark ribbon of road was already cast into darkness by the whaleback mountain’s shadow, some lights came on around the walls and gates of the White Spring Spa Inn, a resort for the wealthy aged. The main building echoed the grace and elegance of Virginia a century ago: pale red brick, which reminded him of Deirdre’s house on the Chesapeake, with massive Doric columns supporting a Greek-keyed portico, a curved driveway empty now of the usual number of limousines. The pale green of golf fairways and tees reached upward in undulating folds behind the resort. The sulphur springs nearby had made the resort an oasis for a hundred years, set in the middle of the Federal Forest, along with the litde town in the notch where the railroad still maintained a wide-roofed, jigsaw depot unchanged from another century’s way of life. There were only a few guests here at this time, according to the report McFee had given him in Washington. He watched wood-smoke lift suddenly from a chimney of one of the separate cottages behind the main building, as someone lighted a fireplace against the evening’s chill. The smoke moved in thin ribbons, driven by the wind that funneled up the valley.

Durell blew on his hands again, rested the rifle on the stone wall, and made himself comfortable. Franklin remained standing, his round face glum, his saddle nose a bit red from the biting wind.

“You’re sure Tomash’ta will come this way?”

“Nothing is sure,” Durell said. “Sit down and try to relax. We’ll know soon enough. He can only enter the Spa from this end. His target is down there. Tomorrow, the target leaves, flies back to Japan. He has to do it now, tonight, or never.”

“What’s so important about the target?” Franklin was querulous. “A Japanese newspaper owner, that’s all.” “Yes.”

“So why is Tomash’ta after him? What makes you people so sure about all this?”

Durell did not take his eyes from the road. He checked the wind, adjusted the scope a hair, sighted through the lens toward the bridge. The bridge crossed the little white-water river about three hundred yards from where he knelt behind the stone wall. The road curved up beyond the bridge and went out of sight to the south, coming up from the new Interstate 64 that ended at the West Virginia line, only a few miles from this place. The wooden trestle and old timbers of the span leaped into sharp focus as he adjusted the knurled knob on the Remington’s sights. He pushed a cartridge home into the chamber.

“Is he coming?” Franklin asked.

“Not yet.”

“This whole thing—the philosophy of it—makes me damned nervous.”

“Shut up and sit down,” Durell said.

“Listen, you can’t—”

“I can. Sit down. Keep quiet.”

I must be getting worried, Durell thought, to let Franklin see my impatience. It was time for Tomash’ta to come barreling down from the notch and across the bridge. Another few minutes and it would be dark. A shot then, to disable the car, would be risky. Not sure of success at all.

He heard a buzz from the portable transceiver and flicked the switch.

“Sam?”

“Yes, Dee.”

“He just passed.”

“A blue Porsche?”

“New York license plate.”

“Good. Go on down to Akuro. Remember to use the back trail. Watch your driving. The van is top-heavy.” “Yes, Sam. Sam!” Her voice was suddenly alarmed. He said quietly, “Yes, Dee, what is it?”

“Sam, there’s something—oh, dear God! Sam—”

The radio crackled.

“Dee?”

There was no reply.

“Deirdre?”

Nothing.

At the same moment, he heard the sound of the car coming around the curve down from the notch, racing for the bridge.

Durell knelt behind the stone wall and slid his finger along the trigger of the Remington. A single shaft of sunlight slipped across the top of the whaleback ridge to the west and splashed brightness into the clump of pine trees behind him. A crow cawed. The throb of the Porsche engine echoed back and forth within the walls of the valley. He kept leading the car through the sights, watching the front wheels. He could not see the driver behind the windshield.

Durell was a tall man, with thick dark hair streaked with silver at the temples; he had a loose, heavy musculature and a manner of moving like a primordial hunter, learned from his boyhood days in the bayous of Louisiana near Peche Rouge. His blue eyes normally darkened in moments of anger or tension; but he did not often permit himself the luxury of emotion. In his business, emotion was something he could rarely afford. Even now, he did not permit the sudden silence of Deirdre’s radio in the van, some two miles down the valley, to distract him from his mission.