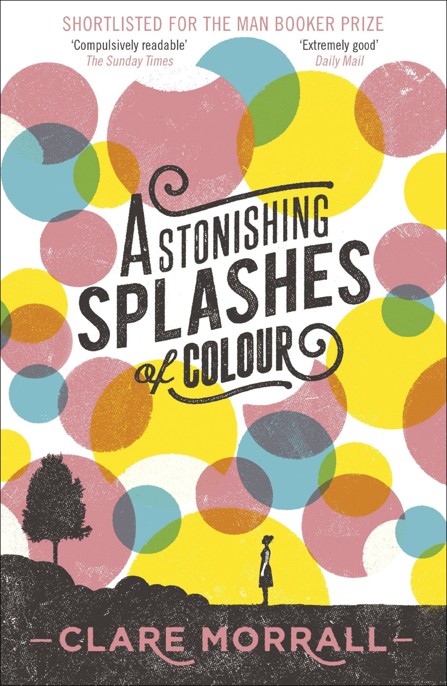

Astonishing Splashes of Colour

Read Astonishing Splashes of Colour Online

Authors: Clare Morrall

astonishing

splashes

of

colour

CLARE MORRALL

For Alex and Heather

“For the Neverland is always more or less an island, with astonishing splashes of colour here and there.”

(from

Peter Pan

by J.M. Barrie)

Contents

Praise for

Astonishing Splashes of Colour

A

t 3:15 every weekday afternoon, I become anonymous in a crowd of parents and child-minders congregating outside the school gates. To me, waiting for children to come out of school is a quintessential act of motherhood. I see the mums— and the occasional dads—as yellow people. Yellow as the sun, a daffodil, the submarine. But why do we teach children to paint the sun yellow? It’s a deception. The sun is white-hot, brilliant, impossible to see with the naked eye, so why do we confuse brightness with yellow?

The people outside the school gates are yellow because of their optimism. There’s a picture in my mind of morning in a kitchen, the sun shining past yellow gingham curtains on to a wooden table, where the children sit and eat breakfast. Their arms are firm and round, their hair still tangled from sleep. They eat Coco Pops, drink milk and ask for chocolate biscuits in their lunchboxes. It’s the morning of their lives, and their mums are reliving that morning with them.

After six weeks of waiting, I’m beginning to recognize individuals, to separate them from the all-embracing yellow mass. They smile with recognition when I arrive now and nearly include

me in their conversations. I don’t say anything, but I like to listen.

A few days ago, I was later than usual and only managed to reach the school gates as the children were already coming out. I dashed in, nearly fell over someone’s pushchair, and collided with another girl. I’ve seen her before: an au pair, who picks up a boy and a girl.

“Sorry,” I said, several times, to everyone.

The girl straightened up and smiled. “Is all right,” she said.

I smiled back.

“I am Hélène,” she said awkwardly. “What is your name?”

“Kitty,” I said eventually, because I couldn’t think of a suitable alternative.

Now when we meet, we speak to each other.

“‘ello, Kitty,” she says.

“Hello, Hélène,” I say.

“Is a lovely day.”

“Yes, it’s very warm.”

“I forgot to put washing out.”

“Oh dear.”

Our conversations are distinctly limited—short sentences with one subject, one verb. Nothing sensational, nothing important. I like the pointlessness of it all. The feeling that you are skimming the surface only, whizzing along on water skis, not thinking about what might happen if you take a wrong turning away from the boat. I like this simple belief, the sense of going on indefinitely, without ever falling off.

“Where do you come from?” I ask Hélène one day. I’m no good with accents.

“France.”

“Oh,” I say, “France.” I have only been to France once, when I was sixteen, on a school trip. I was sick both ways on the ferry,

once on some steps, so everybody who came down afterwards slipped on it. I felt responsible, but there was nothing I could do to stop people using the stairs.

Another mother is standing close to us with a toddler in a pushchair. The boy is wearing a yellow and black striped hat with a pompom on it, and his little fat cheeks are a brilliant red. He is holding a packet of Wotsits and trying to cram them into his mouth as quickly as possible. His head bobs up and down, so that he looks like a bumble bee about to take off.

“Jeremy, darling,” says his mother, “finish eating one before starting on the next.” He contemplates her instructions for five seconds and then continues to stuff them in at the same rate as before.

She turns to Hélène. “What part of France?”

Hélène looks pleased to be asked. “Brittany.”

James would know it. He used to go to France every summer. Holidays with his parents.

One of Hélène’s children comes out of school, wearing an unzipped red anorak and a rucksack on his back in the shape of a very green alligator. The alligator’s scaly feet reach round him from the back and its grinning row of teeth open and shut from behind as he walks.

“‘ello, Toby,” says Hélène.

“Have we got Smarties today?” he demands in a clear, firm tone. He talks to Hélène with a slight arrogance.

Hélène produces a packet of chocolate buttons.

“But I don’t like them. I only like Smarties.”

“Good,” she says and puts the buttons back in her bag.

He hesitates. “OK then,” he says with a sigh, wandering off to chat to his friends with the buttons in his pocket. His straight blond hair flops over his eyes. If he were mine, I’d have taken him to a barber ages ago.

Hélène turns to me. “We walk home together? You know my way?”

“No. I live in the opposite direction to you.”

“Then you come with me to park for a little while? Children play on swings?”

She is obviously lonely. It must be so hard to come to Birmingham from the French countryside. How does she understand the accent, or find out the bus fares and have the right change ready?

“I have to get back,” I say. “My husband will be expecting me.”

She smiles and pretends not to mind. I watch her walk miserably away with her two children and wish I could help her, although I know I can’t. She chose the wrong person. The yellow is changing. I can feel it becoming overripe—the sharp smell of dying daffodils, the sting and taste of vomit.

When I walk home, I remember being met from school by my brothers, twenty-five years ago. It was never my father—too busy, too many socks to wash, too many shirts to iron. I never knew which brother it would be. Adrian, Jake and Martin, the twins, or Paul. I was always so pleased to see them. Paul, the youngest, was ten years older than me, and it made me feel special to be met by a teenage brother, a nearly-man. None of them looked alike, but my memory produces a composite brother. I don’t have a clear picture of him. I remember only the joy of seeing him there.

“Kitty!” this composite brother would call, and I’d feel important as I walked away with him, my empty lunchbox rattling in my plain brown shoulder bag.

They all called me Kitty, my brothers and my father. It used to be Katy, but we had a cat once and when anyone called Kitty, I came running. They often tell people this joke; each time they tell it, it expands and becomes more vivid, so I have the whole

story in my head now. The cat was black, they tell me, black as my hair, with white whiskers and blue eyes. I often try to remember him, and sometimes I almost can, but it’s like a poster flashing past when you’re on the train—there, but too fast to catch.

The cat got run over and died, so I moved along and took its place.

We had an older sister once, too, who I never knew. Dinah. She ran away before I was born, so I took her place as well. I’m good at filling gaps.

A few days later, Hélène approaches me again outside the school. “Kitty?”

I smile at her, but there’s a smell of danger in the situation, so I don’t say anything.

“Will you need to ‘urry after school?”

She’s rehearsed this speech, trying to get her tenses right.

“I’m always in a hurry,” I say.

“I am wondering …”

I wait, feeling my stomach churning. I should learn to listen to my stomach. It seldom makes a mistake.

“Perhaps I can walk a little way ‘ome with you? I want to make friends. I have no friends in Birmingham …” She has difficulty with Birmingham. She divides the three syllables precisely, but loses the ‘h’ in ‘ham’. Her voice tails away.

“I don’t think so. You’d have to wait ages for me. Henry’s always late out.”

“I don’t mind. Children are ‘appy with Smarties.”

I’m running out of excuses.

The children are pouring out now, all on top of each other, shouting, running, arguing. Henry is not among them. Henry my baby, who never comes when I want him. Eventually, there’s

only me and Hélène left. Even the teachers are leaving in their cars.

“Your son is very late,” she says. Her children are walking along the low wall at the entrance with their arms stretched out. Toby is faster than his sister and keeps nudging her along from behind, trying to hurry her up.

“Stop, Toby,” says Hélène. “You ‘ave accident.”

They ignore her.

“He likes to help with the library,” I say cheerfully.

“I wait,” she says. “Is nice to have someone to talk to.”

No, I think. I don’t want anyone with me.

We wait another five minutes.

“Look,” I say. “I’ll go in and find him. You go ahead, and we’ll walk together another time.”

But she sits down on the end of the small wall. “I wait,” she says.

I walk towards the school. Just before I reach the main doors, I look back and see she’s still there, slumped on the wall, ignoring the children. I see Toby push his sister over and hear her wails as I enter the building. There’s nothing I can do about it.

Inside, the corridor is lined with photographs of children in a play. Henry and Gretel—no, Hansel, not Henry. There’s one of the gingerbread house, which has giant Smarties down one wall and liquorice allsorts down another. The roof is made up of huge chocolate fingers. There are several photographs of the witch, crouched under a black cape. The girl’s face is all screwed up behind her glasses; she is clearly enjoying the challenge. I stop for some time and examine a picture of Hansel and Gretel, holding hands, alone in the woods. They are in a single spotlight, surrounded by darkness, so they look very small. Their eyes are very big and round and frightened. You can see that they are lost.

Further on, there are pieces of writing, pinned up on a purple

background. “My Best Friend” is the title, and under the writing they have drawn a picture of their best friend.

The name Henry Woodall catches my eye and I stop to read it.

My best friend is Richard Jenkins. He is in my class at school, but he has a wheelchair so we push him everywhere. I wish I had a wheelchair. It must be really good fun—

“Can I help you?”

I jump and turn round, to find myself facing a woman with a stern, authoritative face. “I’m sorry,” I say. “I was looking for my nephew, but I think I must have missed him.”

She is tall, older than me, and she wears an olive crinkled cotton dress that reaches nearly to her ankles, with a loose beige cardigan over the top. I am convinced that she is the headmistress.