Attila the Hun (20 page)

Authors: John Man

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Ancient, #Rome, #Huns

A

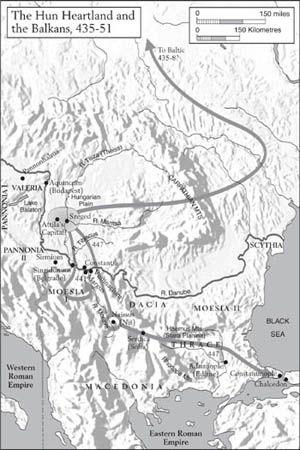

few dribs and drabs of tribute, the odd diplomatic gift – it was simply not enough to keep a restless people happy. To retain power, Attila had to seize the initiative, fast. And so, in 447, he went on the warpath. His aims were threefold: one, to get as much loot as he could as quickly as possible; two, to ensure he could do this again in the future; and three, at the same time to deny the eastern empire any chance of retaliation. This meant occupying the whole Danube frontier region, taking over the river with its fleet, and occupying the cities that acted as the empire’s outposts. Previously, when the Huns were consolidating, they had avoided territorial gain; but Attila’s new ambitions demanded expansion. For the first time, Attila was seeking territory, en route to empire.

Of the 447 campaign itself there are few details. Two things seem certain: that the Huns reached but could not take Constantinople; and that they destroyed many cities in the Balkans. How events unfolded exactly is not recorded, so the following sequence is my conjecture, the reason for which I will explain later.

Consider what this ex-nomad was up against. He could advance whenever he liked, but with what war aims? Surely not simply to ravage and pillage an

already ravaged and pillaged countryside. Wealth lay in towns, of which there were several. But they were well defended, with thick, high walls against which mounted archers would be useless. There is only one way for nomads to take cities, and that is to besiege them so thoroughly that the inhabitants are starved out, always assuming that no heavily armoured reinforcements arrive. That means a siege of several months, during which a hungry army grows restless for lack of loot. No, this time, the Huns would have to take cities.

What of the greatest prize of all, Constantinople? Attila had never been that far south, but he would have known what awaited him if he got there. It was quite a march. From the Hungarian plains you would follow the Tisza for 160 kilometres to Belgrade, then the Morava for a further 180 kilometres down to well-defended Naissus (Niš as it is today). Another 120 kilometres would take you through the narrow valley of the Nišava, where the railway runs now, to Sofia; picking up the Maritsa for the ancient road across southern Bulgaria, where the mountains give way at last to flatter ground and the Turkish town of Adrianople (now Edirne, 220 kilometres), after the final 160 kilometres, making in all a march of 840 kilometres, you would see before you the totally impregnable walls of Constantinople.

The city was now defended by the new Theodosian Walls built by Anthemius after 413. The walls endure to this day, the russet brickwork looming up from the plain. They are much eroded now, but in 445 they were one of the world’s wonders, running from river to sea for 5 kilometres, lined with hewn stone at their bases, mounting like a stairway. An attacker first faced a moat, 20 metres wide, 10 metres deep, partitioned by locks, each section having its own pipes that could flood it and also carry water to the defenders. Then came a parapet – a

peribolo

, as it was known – some 20 metres wide, which would of course be manned by defenders. Once they were cleared, invaders came up against the outer wall, some 10 metres high, with a roadway along the top, and punctuated with guard towers. Beyond this another parapet, 15 metres wide, and finally the inner wall, up to 20 metres high, wide enough at the top for soldiers to parade. Every 50 metres along its whole length rose a tower. Each of its 10 gates had a drawbridge that was removed entirely in time of siege.

If facts and figures do not impress, listen to the awed words of Edwin Grosvenor, Professor of History at Amherst College, Massachusetts, one-time history professor in Constantinople, in his 1895 account of the city:

3

In days when the cannon was unknown, the most dauntless commander and the mightiest army might well shrink back in terror at the sight of such tremendous works. Like a broad, deep, bridgeless river stretched the moat in its precipitous sheath of stone. Even were it crossed and its smooth, high face of rock surmounted, there rose beyond the formidable front of

the outer wall and towers, defended on the vantage ground of the

peribolos

by phalanxes of fighting men. And if those bastions were carried, and their defenders driven back in rout inside the city, there loomed beyond, mocking the ladder and the battering-ram, the adamantine, overawing inner wall. Along its embrasured top the besieged might stroll, and laugh to scorn the impotent assault of hitherto successful but now baffled foes.

No enemy ever managed to breach this barrier until the Turks took the city in 1453, and they managed it because they deployed an 8.5-metre bombard that was hauled by 60 oxen and could lob half-tonne balls from a kilometre away. Attila would not have dreamed of making the attempt.

But he was granted a chance for easy victory, a heaven-sent chance it must have seemed, for at the end of January 447 the city was struck by a terrible earthquake that turned whole sections of the new wall to rubble. The emperor led a congregation of 10,000, barefoot in deference to God’s will, through the rubble-strewn streets to a special service of prayer. But there would be no deliverance from the barbarian menace without hard, fast labour. The work was taken in hand by the praetorian prefect Cyrus, poet, philosopher, art lover and architect, who had already been responsible for more public buildings than anyone since the time of Constantine.

It could well have been that this was the very moment Attila was preparing to head south. One interpretation

of the sources is that, upon hearing news of the earthquake and the collapse of the walls, he rushed together an army and led it on a hard march through the Balkans to Constantinople. If there is anything in this conjecture, then the city would have been in a complete panic at his approach. There is one hint that this is how it might have been. Callinicus, a monk living near Chalcedon (modern Kad1köy), across the Hellespont from Constantinople, recalled the horrors 20 years later:

The barbarian people of the Huns, the ones in Thrace, became so strong that they captured more than 100 cities, and almost brought Constantinople into danger, and most men fled from it. Even the monks wanted to run away to Jerusalem. There was so much killing and blood-letting that no one could number the dead. They pillaged the churches and monasteries, and slew the monks and virgins . . . They so devastated Thrace that it will never rise again.

According to the fifth-century Syrian writer Isaac of Antioch, the city was saved only by an epidemic among the would-be invaders. Addressing the city, he says, ‘By means of sickness he [God] conquered the tyrant who was threatening to come and take thee away captive.’ In fact, Isaac makes the same point again and again. ‘Against the stone of sickness they stumbled . . . with the feeble rod of sickness [God] smote mighty men . . . the sinners drew the bow and put their arrows on the string, then sickness blew through [the host] and hurled

it into wilderness.’ It is all very vague; but perhaps it is significant that there is no mention of an assault, and certainly no siege engines.

That was because Cyrus had been an answer to the city’s prayers. The walls were repaired in double-quick time. Inscriptions in Greek and Latin, still visible to Grosvenor when he was gathering material for his book in the 1880s, praised the achievement of the prefect, who had ‘bound wall to wall’ in 60 days: ‘Pallas herself could hardly have erected so stable a fortification in so short a time.’ Attila would have been confronted not by enticing gaps in a ruined wall, but by the whole restored and impregnable edifice. A wasted journey, then; though he may have drawn a tiny consolation that a decision already taken had now to be followed through.

That decision, I suggest, was to adopt a whole new type of warfare, which owed little to the Huns’ nomadic past. The most vivid record of the 447 Balkan campaign is Priscus’ description of the siege of Naissus, the consequences of which he saw for himself two years later. The Huns, not being city people, would not have been good at sieges. Yet over the last few years they had learned much from their Roman enemies to east and west, and now they put their research and development to good use in a massive, mechanized assault. Naissus lies on the river now called the Nišava. The Huns decided to cross by building a bridge, which would have been not of the usual design but a quickly built pontoon of planks on boats. Across this came ‘beams mounted on wheels’ – siege towers of some kind,

perhaps tree-trunks fixed to a four-wheeled frame. With the details given by Priscus, it is possible to guess how they worked. Above the frame was a platform protected by screens made of woven willow and rawhide, thick and heavy enough to stop arrows, spears, stones and even fire-arrows, but with slits through which the attackers could fire. How many bowmen on the platform? Shall we say four? Below, well protected, were another team of four (or perhaps eight) who pedalled the wheels. There could have been a third team behind, steering the contraption with a long lever. There were ‘a large number’ of these siege towers, which, when in place, delivered such a hail of arrows that the defenders fled from the walls. But the towers were not high enough to reach the ramparts, not up to the standards of classical siege towers like the

helepolis

(‘city-taker’) used by Philip of Macedon when he tried to take Byzantium in 340

BC

, or other towers that were supposedly up to 50 metres high (an extraordinary size: even half that height would be astonishing). Nor is there any mention of drawbridges, vital if the assault were to be carried through, which had been used in siege towers since the time of Alexander the Great 800 years previously. The Huns were learning, but they had a way to go yet.

Now the Huns brought up their next devices: iron-pointed battering-rams slung on chains from the point where four beams came together, like the edges of a pyramid. These too were screened by willow and leather armour, protecting teams who used ropes to swing the rams. These were, says Priscus, very large

machines. They needed to be, because their job was to batter down not only the gates but also the walls themselves. The defenders, returning to the ramparts, had been waiting for this moment. They released wagon-sized boulders, each of which could smash a ram like a sledgehammer blow on a tortoise. But how many giant boulders could have been stored on the battlements, and how many men were ready to risk the hails of arrows to drop them? And how many siege towers and how many rams did it take to assure victory – 20, 30, 50 of each? Priscus gives no details. Whatever the actual numbers, these tactics would have demanded a huge investment of time, energy, expertise and experience – armies of carpenters and blacksmiths, months of preparations, wagonloads of equipment. Attila’s army was not yet something to rival the best that Rome and Constantinople could muster; but it was too much for Naissus. With the walls kept clear by a steady rain of arrows, the rams ate away at the stone even as the Huns finished off their assault by deploying scaling ladders, and the city fell.

Naissus was wrecked. When Priscus travelled past it two years later, the bones of the slain still littered the riverbank and the hostels were almost empty (but at least there

were

hostels, and people: devastation was never total, and there were always survivors to make a go of reconstruction).

How are we to put these events together? Some historians assume that Attila took Thrace town by town, working his way down to Constantinople. If so, what happened to the siege machinery which would

have been vital to take the city? Actually, it wouldn’t have been good enough to tackle Anthemius’ new walls, and he would have known that; so why even bother to get it there? My feeling is that he raced to the capital in the hope of finding its walls still in ruins from the earthquake, found them intact, retreated, and met up with his advancing siege machines to take out easier targets like Naissus. In this way he could hold the eastern empire to ransom anyway, get piles of booty, and gain vital experience in siege warfare that would stand him in good stead down the line, especially if and when he wanted to move against Constantinople at some later date.

Theodosius sued for peace, and was given it – on Attila’s terms.

4

Fugitives were handed over, the ransom for Roman captives raised from 8 to 12

solidi

, the arrears – 6,000 pounds of gold – paid, the annual tribute tripled to 2,100 pounds. To the Huns, this was real money: $38 million down, with $13.5 million to follow every year, a river of gold for pastoral nomads. Roman sources claim that Constantinople was being bled dry. When the tax collectors came to collect, rich easterners had to sell their furniture, even their wives’ jewels, to raise the money. Some were said to have committed suicide.