Attila the Hun (5 page)

Authors: John Man

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Ancient, #Rome, #Huns

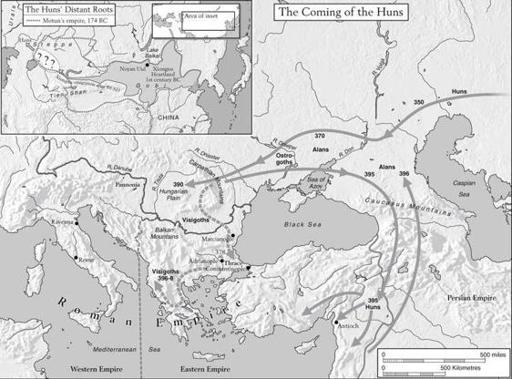

These lightly armed, fast-moving horsemen were the first Huns to reach central Europe. It was their relatives who had unleashed the whirlwind that had blown the Goths across the Danube. Shortly, under the most ruthless of their leaders, they too would cross the river, with consequences for the decaying empire far in excess of anything wrought by the Goths.

NO-ONE KNEW WHERE ATTILA’S PEOPLE CAME FROM

. People said they had once lived somewhere beyond the edge of the known world, east of the Maeotic marshes – the shallow and silty Sea of Azov – the other side of the Kerch straits that links this inland sea to its parent, the Black Sea. Why and when had they come there? Why and when did they start their march to the west? All was a blank, filled by folklore.

Once upon a time, Goth and Hun were neighbours, divided by the Kerch straits. Since they lived either side of the straits, the Goths in Crimea on the western side, the Huns over the way on the flat lands north of the Caucasus mountains, they were unaware of each other. One day a Hun heifer, stung by a gadfly, fled through the marshy waters across the straits. A cowherd, in

pursuit across the marshes, found land, returned, and told the rest of the tribe, which promptly went on the warpath westward. It is a story that explains nothing, for many tribes and cultures depicted their origins in terms of an animal guide. A suspiciously similar tale had long been told of Io, a priestess changed into a heifer by her lover Zeus. Io, as heifer, was driven out of Inner Asia by a gadfly sting, crossing these very straits, swimming over seas, via Greece, where the Ionian islands were named after her, until she arrived at last in Egypt; and it was as a bull that Zeus carried Io’s descendant Europa off to establish civilization in the continent named after her. So such tales about the Huns satisfied no-one. To fill the gap, western writers came up with a dozen equally wild speculations. The Huns were sent by God as a punishment. They had fought with Achilles in the Trojan war. They were any of the Asian tribes named by ancient authors, ‘Scythian’ being the most popular option, since the epithet was widely applied to any barbarian tribe. The fact is that no-one knew – but no-one liked to admit his ignorance. It was important, too, for authors to show off their knowledge of the classics, for, as every literate person knew, it was literature that marked the civilized from the barbarian. If as a Roman you mentioned Scythians or Massegetae, at least you knew your Herodotus, even if the Huns were a blank.

The Huns’ tribal victims were no better informed. According to the Gothic historian Jordanes, a Gothic king had discovered some witches, whom he expelled into the depths of Asia. There they mated with evil

spirits, producing a ‘stunted, foul and puny tribe, scarcely human and having no language save one which bore but slight resemblance to human speech’. They started on their rampage when huntsmen pursued a doe (no heifer, gadfly or cowherd in this version) across the Straits of Kerch, and thus came upon the unfortunate Goths.

Academics don’t like holes like this, and come the Enlightenment a French Sinologist, Joseph de Guignes, tried to fill it. De Guignes – as he is in most catalogues; or Deguines, as he himself spelled his name – is a name that usually appears in academic footnotes, if anywhere. He deserves more, because his theory about Hun origins has been a matter of controversy ever since. At present, it’s making a comeback. It may even be true.

Born in 1721, de Guignes was still in his twenties when he was appointed ‘interpreter’ for oriental languages at the Royal Library in Paris, Chinese being his particular forte. He at once embarked upon the monumental work that made his name. News of this brilliant young polymath spread across the Channel. In 1751, at the age of 29, he was elected to the Royal Society in London – one of the youngest members ever, and a foreigner to boot. He owed this honour to a draft displaying, as the citation remarks, ‘everything that one might expect from a book so considerable, which he has ready for the press’. Well, not quite. It took him another five years to get his work on the press, and a further two to get it off; his

Histoire générale des Huns, des Turcs et des Mogols

was published in five volumes

between 1756 and 1758. The gentlemen of the Royal Society would have forgiven the delay, for de Guignes seemed about to emerge as a shining example of the Enlightenment scholar. He should have become a major contributor to the cross-Channel exchange of knowledge and criticism that led to the translation of Ephraim Chambers’

Cyclopedia

in the 1740s and its extension under the editorship of Denis Diderot into the great

Encyclopédie

, the first volume of which was published in the year of de Guignes’ election to the Royal Society. In fact, de Guignes never escaped the confines of his library, never matched the critical spirit of his contemporaries. His big idea was to prove that all eastern peoples – Chinese, Turks, Mongols, Huns – were actually descendants of Noah, who had wandered eastwards after the Flood. This became an obsession, and the subject of his next book, which sparked a sharp riposte from sceptics, followed by an anti-riposte from the impervious de Guignes. He remained impervious up to his death almost 50 years later. His history was never translated into English.

But one aspect of his theory took root, and flourished. Attila’s Huns, he said, were descendants of the tribe variously known as the ‘Hiong-nou’ or Hsiung-Nu, now spelled Xiongnu, a non-Chinese tribe, probably of Turkish stock. After unrecorded centuries of small-time raiding, these people founded a nomadic empire based in what is now Mongolia in 209

BC

(long before the Mongols came on the scene). He does not argue his case, simply stating as a fact that the ‘Hiong-nou’ were the Huns, period. ‘First Book,’ he starts:

‘History of the Ancient Huns.’ At one unproven stroke, he had vastly extended the range of his subject by several centuries and several thousand kilometres.

It was an attractive theory, because something at least was known about these people in the eighteenth century, to which a good deal more has since been added; so much, indeed, that it is worth looking more deeply at the Xiongnu to see what the Huns may have lacked and may have wished to regain as they trekked westward to a new source of wealth.

T

he Xiongnu were the first tribe to build an empire beyond China’s Inner Asian frontier, the first to exploit on a grand scale a way of life that was relatively new in human history. For 90 per cent of our 100,000 years as true humans, we have been hunter-gatherers, organizing our existence around seasonal variations in the environment, following the movements of animals and the natural flourishing of plants. Then, about 10,000 years ago, the last great ice sheets withdrew and social life began to change, relatively rapidly, giving rise to two new systems. One was agriculture, from which cascaded the attributes that came to define today’s world – population growth, wealth, leisure, cities, art, literature, industry, large-scale war, government: most of the things that static, urban societies equate with civilization. But agriculture also provided tractable domestic animals, with which non-farmers could develop another lifestyle entirely, one of wandering herders – pastoral nomadism, as it is called. For these herders a new world beckoned: the sea of grass,

or steppe, which spans Eurasia for over 6,000 kilometres from Manchuria to Hungary. Herders had to learn how best to use the pastures, guiding camels and sheep away from wetter areas, seeking limey soils for horses, making sure that cattle and horses got to long grass before sheep and goats, which nibble down to the roots.

The key to the wealth of the grasslands was the horse, tamed and bred in the course of 1,000 years to create a new sub-species – a stocky, shaggy, tough and tractable animal that became invaluable for transport, herding, hunting and warfare. Herdsmen were now free to roam the grasslands and exploit them by raising other domestic animals – sheep, goats, camels, cattle, yaks. From them came meat, hair, skins, dung for fuel, felt for clothing and tents, and 150 different types of milk product, including the herdsman’s main drink, a mildly fermented mare’s-milk beer. On this foundation, pastoral nomads could in theory live their self-contained and self-reliant lives indefinitely, not wandering randomly, as outsiders sometimes think, but exploiting familiar pastures season by season.

Pastoral nomads were also warriors, armed with a formidable weapon. The composite recurved bow, similar in design across all Eurasia, ranks with the Roman sword and the machine-gun as a weapon that changed the world. The steppe-dwellers had all the necessary elements – horn, wood, sinew, glue – to hand (though they sometimes made bows entirely of horn), and over time they learned how to combine them for optimum effectiveness. Into a wooden base the maker would splice horn, which resists compression, and

forms the bow’s inside face. Sinews resist extension, and are laid along the outside. The three elements are welded together with glue boiled from tendons or fish. This quick recipe gives no hint of the skills needed to make a good bow. It takes years to master the materials, the widths, the lengths, the thicknesses, the taperings, the temperatures, the time to set the shape, the countless minor adjustments. When this expertise is applied correctly with skill and patience – it takes a year or more to make a composite bow – the result is an object of remarkable qualities.

When forced out of its reverse curve and strung, a powerful bow stores astonishing energy. The earliest known Mongol inscription, dated 1225, records that a nephew of Genghis Khan shot at a target of some unspecified kind and hit it at a distance of some 500 metres; and, with modern materials and specially designed carbon arrows, today’s hand-held composite bows fire almost three-quarters of a mile. Over that kind of distance, of course, an arrow on a high, curving flight loses much of its force. At close range, say 50–100 metres, the right kind of arrowhead despatched from a ‘heavy’ bow can outperform many types of bullet in penetrative power, slamming through half an inch of wood or an iron breastplate.

Arrowheads had their own sub-technology. Bone served well enough for hunting, but warfare demanded points of metal – bronze or iron – with two or three fins, which would slot onto the arrow. The method for mass-producing socketed bronze arrowheads from reusable stone moulds was probably invented in the

steppes around 1000 BC, making it possible for a rider to carry dozens of standard-sized arrows with a range of metal heads. To produce metal arrowheads pastoral nomadic groups had metallurgists, who knew how to smelt iron from rock, and smiths with the tools and skills to cast and forge: both specialists who would work best from fixed bases and who, during migration, needed wagons to transport their equipment.

Thus, towards the end of the first millennium BC, steppeland pastoral nomadism was evolving into a sophisticated new way of life, supporting herders, some of whom doubled as artisans – carpenters and weavers as well as smiths – and most of whom, women included, doubled as fighters. As opposed to the static, agricultural societies south and east of the great deserts of Central Asia, these were people committed to mobility. Expertise with horses, pastures, animals, bows and metallurgy threw up leaders of a new type who could control the flow of animals and access to the best pastures, and thus marshal the resources for conquest. As their steppeland economies flourished, these leaders welded together intertribal alliances, armies and, finally, from about 300

BC

, several empires. But this evolution produced a different type of society. Empires gather wealth and have to be administered. They need headquarters – a capital – and other smaller towns, all forming an urbanized stratum on top of traditional nomadic roots. Among these empires, the first and possibly the greatest before the rise of the Mongol empire was that of the Xiongnu.

* * *