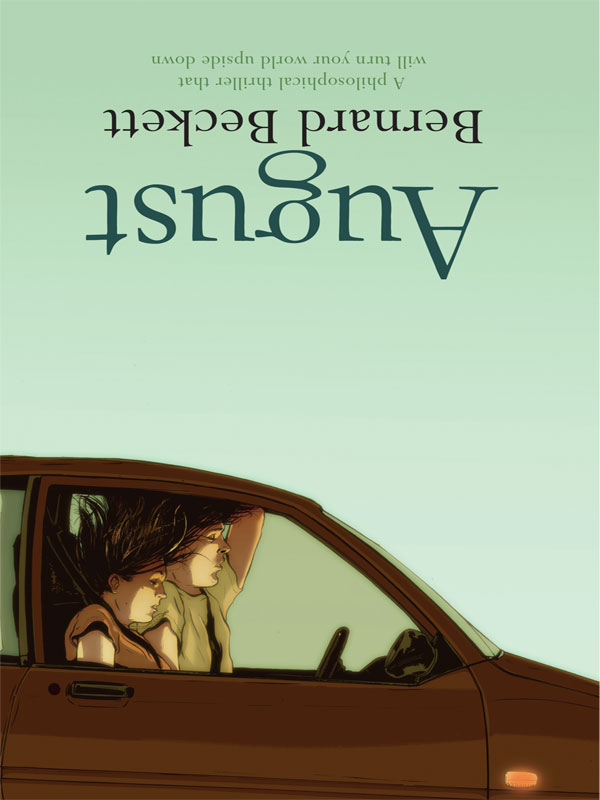

August

PRAISE FOR BERNARD BECKETT AND

GENESIS

âWarning: This book may change your life!â¦The idea

of everything will be thrown into doubt and profound

uncertainty.'

Guardian

âSophisticated sci-fi that explores thorny issues in

philosophy and scienceâ¦Beckett presents a series of

philosophical conundrums with lucid and penetrating

intelligence, and weaves them into a bleak but compelling

futuristic vision.'

Age

âBeckett accelerates the pace and heightens the tension until

his narrative reaches a conclusion so shocking, it's like a

blow to the head.'

Weekend Australian

âHighly originalâ¦It gripped me like a vice.'

Jonathan Stroud

âAnaximanda is a brilliant creation.'

New Zealand Books

âThis is a story rich in resonance and more than a few good

plot twists.'

Courier-Mail

âAn intricate enquiry into the nature of human

consciousness and artificial intelligence.'

Financial Times

Beckett raises enough philosophical questions to keep an

intelligent reader thinking for weeks.'

Independent on Sunday

Other titles by Bernard Beckett

Lester

Red Cliff

Jolt

âfinalist 2002 NZ Post Book Award

No Alarms

Home Boys

Malcolm and Juliet

âwinner 2007 NZ Post Book Award, winner 2005 Esther Glen Award

Deep Fried

(with Clare Knighton)âfinalist NZ Post Book Award

Genesis

âwinner 2010 young adult category of the Prix Sorcières, France; winner 2007 Esther Glen Award; winner 2007 NZ Post Book Award

Falling for Science: Asking the Big Questions

Acid Song

Bernard Beckett is a multi-award-winning author of books for adults and young adults and one of New Zealand's most outstanding writers. He lives near Wellington with his wife and two sons.

August

Bernard Beckett

The paper in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Bernard Beckett 2011

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by The Text Publishing Company, 2011

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Susan Miller

Typeset by J&M Typesetters

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Beckett, Bernard, 1968â

Title: August / Bernard Beckett.

Edition: 1st ed.

ISBN: 9781921758041 (pbk.)

Dewey Number: NZ823.2

For Clare, with love   Â

Contents

For a moment the balance was uncertain. The headlights stabbed at the thick night. A rock loomed, smooth and impassive, then swung out of the frame. A stunted tree rushed at him, gnarled and prickly. The seat pushed hard, resisting his momentum. Road, rock again, grass, gravel. The forces resolved their differences and he was gliding, a dance of sorts, but he was deaf to its rhythm, just as he was deaf to her screams. Instinct fought the wheel, but the future drew them in.

They were floating, tumbling together in a machine not made for tumbling, weightless and free. He considered the physics: gravity recast as acceleration. An odd thought to have, but what thought isn't odd when death breathes close and sticky? The world slowed. He could not look at her.

The dance broke with a dull thud and the roof above them crumpled. They bounced. The lights went out and collisions vibrated through him, dissolving the border between feeling and sound. His insides he supposed were acting out their own small version of this greater play. He had heard of it, hearts so determined in their trajectories that they ripped free from their moorings.

With each thud the terrain absorbed momentum. That word again. All is physics. It ended with a shudder. His, hers, the car's. They rocked but did not roll. There in the darkness on a disinterested slab of stone their stories settled into silence.

She was no longer screaming. He was still alive. This was as far as his certainty extended. He considered the possibility he was upside down. Something, perhaps his seatbelt, was digging into his throat. Adrenaline fizzed through him.

The humming untangled itself into distinct sounds. Steam hissed from a punctured pipe. He heard the grating of stressed metal and some part of the engine ticking as it cooled, counting down the seconds. A groan.

Her breath was a warm whisper across his nose. We must be close now, he thought, her head and mine.

He should have said something. It was the polite thing to do. St Augustine's had carved the importance of politeness deep into its charges.

There are no exceptions to this titanium rule.

Manners first. Always.

He was letting the old school down, then; he had thoughts only for himself. A warm stream of blood originating somewhere below his collar trickled up his neck and over his chin (so, definitely upside down). His mouth filled with the taste of salt and iron. A first awareness of pain pulsed through him. Perhaps I am dying, he thought. Certainly he was injured.

He was to blame. She was here because he had brought her here; this point could not be denied. And so, as the rector would have insisted, she was his responsibility. He held his breath to focus on the sound of hers, leaning towards the point where he imagined the mouth might be. Her air came short and fast, shallow with fear. He could detect no bubbling; her lungs weren't filling up. She will live, he decided. The evidence inadequate, the conclusion reassuring.

He reached slowly towards his seatbelt buckle but searing pain beat him back, as sharp and precise as a cleaver.

Something new. A whispering like wind but close, familiar. He stared intently at the blackness, as though the secret of the fragmented sounds was written there. She tried again.

âI can hear you.' Her words landed as spray on his face.

âSorry.' His inadequate reply.

She was slowly gaining control of her breathing. She swallowed noisily. âI just meantâ¦you haven't said anything.'

âI was thinking,' he said.

âThinking what?'

âWondering. Wondering if I was dying.'

âAre you?'

âI don't know. My shoulder's definitely broken.'

âMy head hurts.'

âI think we must be upside down.'

âYou don't want to know how it hurts?' she asked.

âI'm not a doctor.'

âBastard.'

âWhat do you want, a diagnosis?' The words disturbed his breathing and he ended with a desperate cough.

âI'd settle for an escape,' she said.

âSome say only death can provide that.'

âSome say a lot of shit.'

âHow does your head hurt?' he asked.

It wasn't meant to be like this. He'd planned every detail.

âI'm Tristan,' he said.

âYou want to know my name?'

âYou'll only lie.'

A long silence. Tristan wondered if she had passed out. âIt was the ice. I lost control on the ice,' he said.

Still there was nothing. âI am sorry.' This time his voice dented. If he could only have that moment back. But which moment? The last moment, before the future sets hard. The hiding place of the soul.

The acrid stench of battery acid touched Tristan's nose. He wondered how this would end, and panic rose in his throat. He spoke only as a way of denying his pain.

âAre you still there?'

âI'm not going anywhere.'

Her voice hovered in the unseen spaces, unnaturally calm. He'd liked it better when she was screaming.

It was wrong to have told her his name. Intimate though their position was, it was no excuse for assuming. This too the rector had explained to the boys. Social ethics was taught at meal time, with their dinner plates steaming before them. They ate only when the rector finished speaking, and he finished speaking only when he was satisfied they had listened. An inspector from the Holy Council visited once during such a lecture but nothing changed. The rector had a way with authority: the powerful lost their nerve around him.

âAre you sure we're upside down?' she asked, out of the cold darkness. Somehow her presence surprised him. How easy, in this tenuous place, to imagine the world in and out of existence.

âI think so. Why?'

âI pissed myself.'

âYou shouldn't tell me that.'

She laughed until it threatened her breathing.

âIt's not funny,' Tristan insisted.

âWe should try to get out,' she said.

âI tried.'

âAnd?'

âIt hurt too much.'

âMore than dying?'

âHard to say.' He imagined her smiling. It strengthened him.

But he did not move. The memory of pain was too fresh, and raw. He heard her wriggling beside him. Something, an elbow, he thought, pressed into his stomach. She grunted with the exertion. There was a hissing sound: air made hard through clenched teeth.