Autobiography of Mark Twain (116 page)

Read Autobiography of Mark Twain Online

Authors: Mark Twain

Headquarters Department of the East.

Dear General: Because I stopped talking for pay a good many years ago, and I could not resume the habit now without a great deal of personal discomfort. I love to hear myself talk, because I get so much instruction and moral upheaval out of it, but I lose the bulk of this joy when I charge for it. Let the terms stand.

General, if I have your approval, I wish to use this good occasion to retire permanently from the platform.

Truly Yours

S.L. Clemens.

Dear Mr. Clemens:

Certainly. But as an old friend, permit me to say, Don’t do that. Why should you ?—you are not old yet.

Yours truly

Fred D. Grant.

Dear General:

I mean the

pay

-platform; I shan’t retire from the gratis-platform until after I am dead and courtesy requires me to keep still and not disturb the others.

What shall I talk about? My idea is this: to instruct the audience about Robert Fulton, and .... Tell me—was that his real name, or was it his nom de plume? However, never mind, it is not important—I can skip it, and the house will think I knew all about it, but forgot. Could you find out for me if he was one of the Signers of the Declaration, and which one? But if it is any trouble, let it alone, I can skip it. Was he out with Paul Jones? Will you ask Horace Porter? And ask him if he brought both of them home. These will be very interesting facts, if they can be established. But never mind, don’t trouble Porter, I can establish them anyway. The way I look at it, they are historical gems—gems of the very first water.

Well, that is my idea, as I have said: first, excite the audience with a spoonful of information about Fulton, then quiet them down with a barrel of illustration drawn by memory from my books—and if you don’t say anything the house will think they never heard of it before, because people don’t really read your books, they only say they do, to keep you from feeling bad. Next, excite the house with another spoonful of Fultonian fact. Then tranquillize them again with another barrel of illustration. And so on and so on, all through the evening; and if you are discreet and don’t tell them the illustrations don’t illustrate anything, they won’t notice it and I will send them home as well informed about Robert Fulton as I am myself. Don’t you be afraid; I know all about audiences, they believe everything you say, except when you are telling the truth.

Truly Yours

S. L. Clemens.

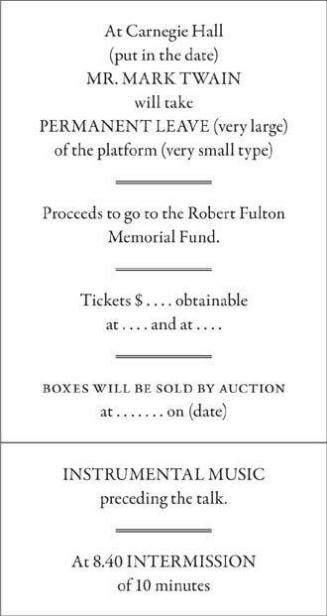

P. S. Mark all the advertisements

“Private and Confidential,”

otherwise the people will not read them. M. T.

Dear Mr. Clemens:

How long shall you talk? I ask in order that we may be able to say when carriages may be called.

Very Truly Yours

Hugh Gordon Miller.

Secretary.

Dear Mr. Miller:

I cannot say for sure. It is my custom to keep on talking till I get the audience cowed. Sometimes it takes an hour and fifteen minutes, sometimes I can do it in an hour.

Sincerely Yours

S. L. Clemens.

Mem

. My charge is

two boxes free

. Not the choicest—

sell

the choicest, and give me any six-seat boxes you please.

SLC

I want Fred Grant (in uniform) on the stage; also the rest of the officials of the Association; also other distinguished people—all the attractions we can get. Also, a seat for Mr. Albert Bigelow Paine, who may be useful to me if he is near me and on the front.

SLC

Private and Confidential

.

Wednesday, March 21, 1906

Mental telegraphy—Letter from Mr. Jock Brown—Search for Dr. John Brown’s

letters a failure—Mr. Twichell and his wife, Harmony, have an adventure

in Scotland—Mr. Twichell’s picture of a military execution—Letter relating

to foundation of the Players Club—The mismanagement which caused

Mr. Clemens to be expelled from the Club—He is now an honorary member.

Certainly mental telegraphy is an industry which is always silently at work—oftener than otherwise, perhaps, when we are not suspecting that it is affecting our thought. A few weeks ago when I was dictating something about Dr. John Brown of Edinburgh and our pleasant relations with him during six weeks there, and his pleasant relations with our little child, Susy, he had not been in my mind for a good while—a year, perhaps—but he has often been in my mind since, and his name has been frequently upon my lips and as frequently falling from the point of my pen. About a fortnight ago I began to plan an article about him and about Marjorie Fleming, whose first biographer he was, and yesterday I began the article. To-day comes a letter from his son Jock, from whom I had not previously heard for a good many years. He has been engaged in collecting his father’s letters for publication. This labor would naturally bring me into his mind with some frequency, and I judge that his mind telegraphed his thoughts to me across the Atlantic. I imagine that we get most of our thoughts out of somebody else’s head, by mental telegraphy—and not always out of heads of acquaintances but, in the majority of cases, out of the heads of strangers; strangers far removed—Chinamen, Hindoos, and all manner of remote foreigners whose language we should not be able to understand, but whose thoughts we can read without difficulty.

7 G

REENHILL

P

LACE

E

DINBURGH

8th March, 1906.

Dear Mr Clemens,

I hope you remember me, Jock, son of Dr John Brown. At my father’s death I handed to Dr J. T. Brown all the letters I had to my father, as he intended to write his life, being his cousin and life long friend. He did write a memoir, published after his death in 1901, but he made no use of the letters and it was little more than a critique of his writings. If you care to see it I shall send it. Among the letters which I got back in 1902 were some from you and Mrs Clemens. I have now got a large number of letters written by my father between 1830 and 1882 and intend publishing a selection in order to give the public an idea of the man he was. This I think they will do. Miss E. T. MacLaren is to add the necessary notes. I now write to ask you if you have letters from him and if you will let me see them and use them. I enclose letters from yourself and Mrs Clemens which I should like to use, 15 sheets typewritten. Though I did not write as I should to you on the death of Mrs Clemens, I was very sorry to hear of it through the papers, and as I now read these letters, she rises before me, gentle and loveable as I knew her. I do hope you will let me use her letter, it is most beautiful. I also hope you will let me use yours....

I am

Yours very sincerely

John Brown

We have searched for Doctor John’s letters but without success. I do not understand this. There ought to be a good many, and none should be missing, for Mrs. Clemens held Doctor John in such love and reverence that his letters were sacred things in her eyes and she preserved them and took watchful care of them. During our ten years’ absence in Europe many letters and like memorials became scattered and lost, but I think it unlikely that Doctor John’s have suffered this fate. I think we shall find them yet.

These thoughts about Jock bring back to me the Edinburgh of thirty-three years ago, and the thought of Edinburgh brings to my mind one of Reverend Joe Twichell’s adventures. A quarter of a century ago, Twichell and Harmony, his wife, visited Europe for the first time, and made a stay of a day or two in Edinburgh. They were devotees of Scott, and they devoted that day or two to ransacking Edinburgh for things and places made sacred by contact with the Magician of the North. Toward midnight, on the second night, they were returning to their lodgings on foot; a dismal and steady rain was falling, and by consequence they had George street all to themselves. Presently the rainfall became so heavy that they took refuge from it in a deep doorway, and there in the black darkness they discussed with satisfaction all the achievements of the day. Then Joe said:

“It has been hard work, and a heavy strain on the strength, but we have our reward. There isn’t a thing connected with Scott in Edinburgh that we haven’t seen or touched—not one. I mean the things a stranger

could

have access to. There is

one

we haven’t seen, but it’s not accessible—a private collection of relics and memorials of Scott of great interest, but I do not know where it is. I can’t get on the track of it. I wish we could, but we can’t. We’ve got to give the idea up. It would be a grand thing to have a sight of that collection, Harmony.”

A voice out of the darkness said “Come up stairs and I will show it to you!”

And the voice was as good as its word. The voice belonged to the gentleman who owned the collection. He took Joe and Harmony up stairs, fed them and refreshed them; and while they examined the collection he chatted and explained. When they left at two in the morning they realized that they had had the star time of their trip.

Joe has always been on hand when anything was going to happen—except once. He got delayed in some unaccountable way, or he would have been blown up at Petersburg when the mined defences of that place were flung heavenward in the Civil War.

When I was in Hartford the other day he told me about another of his long string of providential opportunities. I think he thinks Providence is always looking out for him when interesting things are going to happen. This was the execution of some deserters during the Civil War. When we read about such things in history we always have one and the same picture—blindfolded men kneeling with their heads bowed; a file of stern and alert soldiers fronting them with their muskets ready; an austere officer in uniform standing apart who gives sharp terse orders, “Make ready. Take aim. Fire!” There is a belch of flame and smoke, the victims fall forward expiring, the file shoulders arms, wheels, marches erect and stiff-legged off the field, and the incident is closed.

Joe’s picture is different. And I suspect that it is the true one—the common one. In this picture the deserters requested that they might be allowed to stand, not kneel; that they might not be blindfolded, but permitted to look the firing file in the eye. Their request was granted.

They stood erect and soldierly; they kept their color, they did not blench; their eyes were steady.

But these things could not be said of any other person present

. A General of Brigade sat upon his horse white-faced—white as a corpse. The officer commanding the squad was white-faced—white as a corpse. The firing file were white-faced, and their forms wobbled so that the wobble was transmitted to their muskets when they took aim. The officer of the squad could not command his voice, and his tone was weak and poor, not brisk and stern. When the file had done its deadly work it did not march away martially erect and stiff-legged. It wobbled.

This picture commends itself to me as being the truest one that any one has yet furnished of a military execution.

In searching for Dr. Brown’s letters—a failure—we have made a find which we were not expecting. Evidently it marks the foundation of the Players Club, and so it has value for me.

Daly’s Theatre

UNDER THE MANAGEMENT OF

A

UGUSTIN

D

ALY. MANAGERS OFFICE

.

New York, Jan 2d 1888.

Mr Augustin Daly will be very much pleased to have Mr S. L. Clemens meet Mr Booth, Mr Barrett and Mr Palmer and a few friends at Lunch on Friday next January 6th (at one oclock in Delmonico’s) to discuss the formation of a new club which it is thought will claim your interest.

R.S.V.P.

All the founders, I think, were present at that luncheon—among them Booth, Barrett, Palmer, General Sherman, Bispham, Aldrich, and the rest. I do not recall the other names. I think Laurence Hutton states in one of his books that the Club’s name—The Players—had been already selected and accepted before this luncheon took place, but I take that to be a mistake. I remember that several names were proposed, discussed, and abandoned at the luncheon; that finally Thomas Bailey Aldrich suggested that compact and simple name, The Players; and that even that happy title was not immediately accepted. However the discussion was very brief. The objections to it were easily routed and driven from the field, and the vote in its favor was unanimous.