Autobiography of Mark Twain (26 page)

Read Autobiography of Mark Twain Online

Authors: Mark Twain

After signing it I spoke doubtfully of my chances, and Paige shed a few tears, as usual, and was deeply hurt at being doubted; asked me if he hadn’t always taken care of me? and had he ever failed of his word with me? hadn’t he always said that no matter

what

happened (meaning a falling-out—which I had suggested) I should have my 9/20 of every dollar he ever got out of the machine, domestic and foreign; that if he died (as I had suggested) his family would see to it that I got my 9/20. Then—

“Here, Charley Davis, take a pen and write what I say.”

He dictated and Davis wrote.

“There, now,” said Paige, “are you satisfied

now?

”

I went on footing the bills, and got the machine really perfected at last, at a full cost of about $150,000, instead of the original $30,000.

Ward tells me that Paige tried his best to cheat me out of my royalties when making a contract with the Connecticut Co.

Also that he tried to cheat out of all share Mr. North (inventor of the justifying mechanism;) but that North frightened him with a lawsuit-threat, and is to get a royalty until the aggregate is $2,000,000.

Paige and I always meet on effusively affectionate terms; and yet he knows perfectly well that if I had his nuts in a steel-trap I would shut out all human succor and watch that trap till he died.

This manuscript—which has not been published before—was left to a degree unfinished, judging from Clemens’s penciled (tentative) revision of its title to “Travel-Scraps from Autobiog.” Now in the Mark Twain Papers, it is thought to be a draft chapter written for the autobiography on that evidence, and also because, in 1900 during a later stay in London, Clemens wrote a sequel about the city entitled “Travel-Scraps II,” which he ultimately inserted in the Autobiographical Dictation of 27 February 1907. The subtitle “London, Summer, 1896,” refers to the events in the piece, not the time of writing, which was clearly soon after the Clemenses arrived in Vienna in late September 1897. The “village” Clemens referred to was the area around Tedworth Square, where they lived from October 1896 until they moved to Weggis, Switzerland, in July 1897 (Notebook 39, TS p. 6, CU-MARK).

Travel-Scraps I

London, Summer, 1896

All over the world there seems to be a prejudice against the cab driver. But that is too sweeping; it must be modified. I think I may say that there is a prejudice against him in many American cities, but not in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Boston; that in Europe, as a rule, there is a prejudice against him, but not in Munich and Berlin; that there is a prejudice against him in Calcutta but not in Bombay. I think I may say that the prejudice against him is strong in London, stronger in Paris, and strongest in New York. There are courteous and reasonable cabmen in Paris, but they seem to be rare. I think that in London four out of every six cabmen are pleasant and rational beings, and are satisfied with twenty-five per cent above legal fare; and that the other two are always ready and anxious for a dispute, and burning to conduct it in a loud and frantic key.

*

The citizen must pay from two to three prices, when he makes his bargain beforehand, and more when he doesn’t. When he makes his bargain beforehand he expects to be overcharged, and is not discontented unless the over-tax is extravagant, because he knows that the legal rate is too low, and that the hack-industry cannot live upon it. The heavy over-charge has kept the traffic down and made it meagre. The legal charge might not be too low if the traffic were as heavy as it ought to be for a city like New York, but it is not likely to expand while hackmen may continue to charge any price they please. And now that the hacks have driven all the business into the hands of the steam and electric companies, the periodical attempts to inaugurate a cheap hack-system in New York will presently begin again, I suppose. Hacks are but little needed in American cities for any but strangers who cannot find their way by tram-lines. The citizen should be thankful for the high hack-rates which have given him the trams; for by consequence he has the cheapest and swiftest city-transportation that exists in the world. London travels by omnibus—pleasant, but as deadly slow as a European

“lift;” and by underground railway, which is an invention of Satan himself. It goes no direct course, but always away around. When the train arrives you must jump, rush, fly, and swarm with the crowd into the first cigar box that is handy, lest you get left. You have hardly time to mash yourself into a portion of a seat before the train is off again. It goes blustering and squttering along, puking smoke and cinders in at the window, which some one has opened in pursuance of his right to make the whole cigar box uncomfortable if his comfort requires it; the fog of black smoke smothers the lamp and dims its light, and the double row of jammed people sit there and bark at each other, and the righteous and the unrighteous pray each after his own fashion. The train stops every few minutes, and there is a new rush and scramble each time. And every quarter of an hour you change cars, and fly thirty yards to a stairway, and up the stairway and fifty yards along a corridor, and down another stairway, and plunge headlong into a train just as it moves off; and of course it is the wrong one, and you must get out at the next station and come back. But it is no matter. If you had stopped to ask the official on duty, it would have been the right train and you would have lost it by stopping to ask; and so none but idiots stop to ask. The next time that you ought to change cars you are not aware of it, and you go on. You keep on going on and on and on, wondering what has become of St. John’s Wood, and if you are ever likely to get to that brick-and-mortar forest; and by and by you pull your courage together and ask a passenger if he can tell you whereabouts you are, and he says “We are just arriving at Sloane Square.” You thank him, and look gratified, look as gratified as you can on the spur of the moment and without sufficient preparation, and step out, saying “It is my station.” And so it is. That is where you started from. It is an hour or an hour and a half ago, and is getting toward bedtime, now. You have been plowing through tunnels all that time, and have been all around under London amongst its entrails, and been in first, second and third-class cars on a third-class ticket, and associated with all sorts of company, from Dukes and Bishops down to rank and mangy tramps and blatherskites who sat with their drunken trunnions in their laps and caressed and kissed them unembarrassed. You have missed the dinner you were aimed for, but you are alive yet, and that is something; and you have learned better than to go by tunnel any more, and that is also a gain. You cannot telephone your friend to go to bed and not keep the dinner waiting. There is not a telephone within a mile of you, and there is not a telephone within a mile of him. Years ago there was a telephone system in England, but in the country parts it is about dead, now, and what is left of it in London has no value. So you send a telegram to your friend, stating that you have met with an accident, and begging him not to wait dinner for you. You are aware that all the offices in his neighborhood close at eight in the evening and it is ten now; it is also Saturday night, and England keeps Sunday; but the telegram will reach his house Monday morning, and when he gets back from business at five in the evening he will get it, and will know then that you did not come Saturday evening, and why.

One little wee bunch of houses in London, one little wee spot, is the centre of the globe, the heart of the globe, and the machinery that moves the world is located there. It is called the City, and it, with a patch of its borderland,

is

a city. But the rest of London is not a city. It is fifty villages massed solidly together over a vast stretch of territory. Each village has its own name and its own government. Its ways are village ways, and the great body of its inhabitants

are just villagers, and have the simple, honest, untraveled, unworldly look of villagers. Its shops are village shops; little cramped places where you can buy an anvil or a paper of pins, or anything between; but you can’t buy two anvils, nor five papers of pins, nor seven white cravats, nor two hats of the same breed, because they do not keep such gross masses in stock. The shopman will not offer to get the things and send them to you, but will tell you where he thinks you may possibly find them. And he is not brusque and fussy and unpleasant, like a city person, but takes the simple and kindly interest of a villager in the matter, and will discuss it as long as you please. They have no hateful city ways, and indeed no ways that suggest that they have ever lived in a city.

In my village there are a lot of little postoffices and one big one—in Sloane Square. One Saturday toward dusk I visited three of the little ones and asked if there was a Sunday mail for Paris; and if so, at how late an hour could I mail my letter and catch it? Nobody knew whether there was such a mail or not, but it was believed that there was. They could not refer to a table of mails, for they had none. Could they telephone the General Postoffice and find out for me? No, they had no telephone. The big office in Sloane Square might know. I went there. There were two or three girls and a woman or two on duty. Yes, there was a Paris mail, they said; they did not know at what hour it left, but they believed it did. Were my questions unusual ones in their experience? They could not remember that any one had asked them before. And those people looked

so

friendly, and innocent, and childlike, and ignorant, and happy, and content.

I lived nine months in that village. I got my predecessor’s mail along with my own, every day. He had left his new address at the postoffice, but that did little or no good. The letters came to me. I reinstructed the carriers now and then; then, for as much as a week afterward I would get my own mail only; after that, I would get the double mail again, as before.

But that was a pleasant village to live in. The spirit of accommodation was everywhere, just as it is in Germany, and just as it isn’t, in a good many parts of the earth. I went to my nearest postoffice one day to send a telegram. The office was in a little shop that had thirty dollars’ worth of miscellaneous merchandise in it, and a young woman was on duty. I was in a hurry. I wrote the telegram, and the young woman examined it and said she was afraid it would not reach its destination. A flaw in the address, perhaps—I do not remember what the trouble was. She wanted to call her husband and advise about the matter. I explained that I was following orders, and that if the man at the other end did not get the telegram he would have only himself to blame. But she was not satisfied with that. She reminded me that it would be a pure waste of money, and I the loser. She would rather call her husband and see about it. She had to have her way; I could not help myself; her kindly interest disarmed me, and I could not break out and say, “Oh, send it just as it is, and let me go.” She brought her husband, and the two reasoned the matter out at considerable length, and finally got it arranged to their satisfaction. But I was not to get away yet. There was a new difficulty. There were apparently more words than necessary, and if I could strike out a word or two the telegram would cost only sixpence. I came near saying I would rather pay four cents extra than lose another three shillings’ worth of time, but it would have been a shame to act like that when they were trying their best to do me a kindness, so I did not say it, but held in and let the ruinous expense of time run on. Amongst us, in the course of time, we managed to gut the telegram of a few of its most necessary words, and then I was free, and paid my sixpence and got back to my work; and I would be glad to repeat that pleasant experience, even at cost of half the time and twice the money. That was a London episode. I am trying to imagine such a thing happening in a New York telegraph office, but there seems to be something the matter with my imagination to-day.

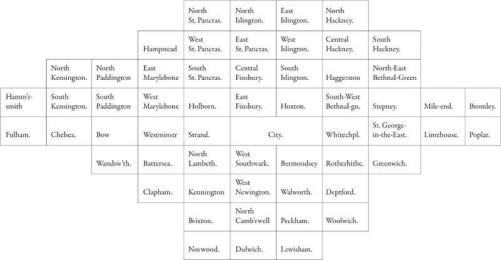

D

IAGRAM OF

L

ONDON

The London ’bus driver does not seem like a city person, but like a blessed angel out of the country. He is often nattily dressed and nicely shaved, and often just the other way; but in either case the man is a choice man, and satisfactory. He hasn’t a hard city face, nor crusty and repellent city ways, nor indeed anything about him which can be called “citified”—that epithet which suggests the absence of all spirituality, and the presence of all kinds of paltry materialisms, and mean ideals, and mean vanities, and silly cynicisms. He is a pleasant and courteous and companionable person, he is kindly and conversational, he has a placid and dignified bearing which becomes him well, and he rides serene above the crush and turmoil of London as undisturbed by it and as unconcerned about it as if he were not aware that anything of the kind was going on. The choice part of the ’bus is its roof; and the choicest places on the roof are the two seats back of the driver’s elbows. The occupants of those seats talk to him all the time. That shows that he is a polite man, and interesting. And it shows that in his heart he is a villager, and has the simplicities and sincerities and spirit of comradeship which belong to a man whose city contacts have been of an undamaging infrequency. The ’bus driver not only likes to talk to his passengers, but likes to have a choice kind of passengers to talk to. I base this opinion upon some remarks made to a friend of mine by a driver toward the end of last February. My friend opened the conversation, along in the King’s Road somewhere: