B0041VYHGW EBOK (126 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Then, Cutter explains, comes the Turn, the moment when the ordinary becomes extraordinary. Covering the birdcage with a scarf, he flattens it. Cutter’s commentary coincides with Robert stepping into the electrical field while Alfred explores the trapdoor area below stage. Finally, after the canary and Robert have disappeared, Cutter’s voice-over says:

But you wouldn’t clap yet. Because making something disappear isn’t enough. You have to bring it back. That’s why every magic trick has a third act—the hardest part. The part we call the Prestige.

As we hear these words, we see him showing Jessie the revived canary—a successful feat of legerdemain—crosscut with Robert’s uneasy audience and shots of Alfred staring at Robert struggling underwater.

Cutter’s voice has been closely miked in a dry recording, lending it the sort of intimate, direct-address perspective we’ll encounter in the diary voice-overs. But now, at the fade-out, in a more hollow timbre, another man’s voice repeats, “The Prestige.” As the new scene fades up, Cutter is in the witness box. His dialogue is now anchored in a more reverberant sound field, suitable to a large courtroom. We realize that his explanation of a trick’s three acts is motivated as his testimony at Alfred’s trial.

Cutter’s voice-over introduces some central themes, such as the idea that a magic trick has an artistic structure that demands both skill and showmanship—the two components that distinguish Alfred and Robert. Cutter also stresses the need to distract the audience, because, he says, the spectator wants to be fooled. This could be taken as a commentary on our own urge to overlook details in watching the film. And Cutter’s stress on bringing back the vanished object establishes the motif that when the Prestige arrives, no one cares about the man in the box.

With respect to plot construction, Cutter’s commentary makes the death of Robert a flashback from the present time of the court proceedings. At the film’s close, we will learn that the canary trick Cutter performs is a sort of flash-forward, referring to a still “later” present time enclosing the whole film. The crosscutting has shuttled us between two moments of story time, while the voice-over has put us in yet a third, the court testimony. That testimony is nonsimultaneous with respect to both lines of visual action; it takes place after the death of Robert but long before the scene with Jessie. This opening not only introduces us to major characters and themes but also establishes the time-juggling shifts that we’ll encounter in the film to come.

Cutter’s voice-over also prepares us for the tight image/sound synchronization that will carry the plot forward. His voice speaks of showing the Pledge object; he shows the canary; cut to Robert displaying his machine. When Cutter says the object probably isn’t normal, we see Alfred tear off his false beard to prove he’s part of the performance. Cutter explains the second phase, and as his voice says, “The Turn,” cut to Robert literally turning to us. Cutter flattens the birdcage as his voice speaks of the “extraordinary”; cut to Robert seized by electricity.

The commentary drops a few hints, too, as when Cutter indirectly introduces the film’s protagonists

(

7.60

,

7.61

).

Later, as Alfred prowls in the stage cellar, studying the water tank, Cutter speaks of the audience “not really looking” at what is going on in the trick. Robert plummets into the tank, the lock snaps shut, and Cutter says, “You want to be—” Cut to him snatching the scarf away, showing that the birdcage has vanished as his voice-over finishes: “—fooled.” Indeed, Alfred will be fooled, since he does not understand Robert’s manipulation of his clones until the end. Cutter’s calm delivery about “bringing back” the ordinary object, timed to his presentation of the canary, serves as an upbeat contrast to the stage act. Jessie applauds, but Robert’s audience doesn’t, because the Prestige (“the hardest part”) is missing. Robert, flailing underwater, will not be brought back—at least, not for some time.

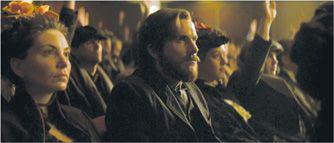

7.60 As Cutter’s voice-over talks about a magician showing us something ordinary, his mention of “a man” is synchronized with the first shot of Alfred, disguised in the audience.

7.61 But Alfred is not the man central to the Pledge. That is Robert himself, seen in the next shot. Along with the editing, the commentary subtly establishes these two as the central antagonists.

This opening could not be as economical and intriguing as it is without Cutter’s voice-over narration. The crosscutting and juxtapositions of dialogue will reappear in the climax and be finally explained in the final shots. Yet there is one more element in the opening passage to consider.

The very first shot of the film fades in on a leftward tracking shot across a field of top hats

(

7.62

).

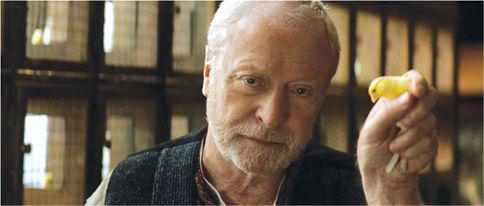

Later we will learn that those are the hats that Tesla has inadvertently cloned in his experiments. The next shot shows a row of canaries in cages

(

7.63

);

one of these will be the star of Cutter’s trick for Jessie

(

7.64

).

In hindsight, we can see that these two shots hint at how both Alfred and Robert accomplish their magic—by using exact copies. In addition, just as a canary has to die in order to disappear, death will haunt each magician’s double. Alfred has given up a great deal for his art, with each twin living only half a life. But Robert has wound up devoting himself to his craft just as passionately. In dying and being reborn every night, he has embraced what Alfred calls “total self-sacrifice.”

7.62 The opening shot of

The Prestige:

The camera tracks over the scattered top hats …

7.63 … and continues to move along several parakeet cages, creating a parallel based on the idea of identical copies.

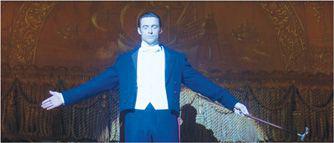

7.64 Addressing Jessie, Cutter also invites us to consider how a magic trick may mislead the audience.

But as usual, sound plays a role, too. At three points in the rest of the film, Alfred will ask someone, “Are you watching closely?” It’s his mocking warning that he will practice some deceptive sleight of hand. At the very start, however, as the camera coasts over the top hats, we hear this line for the first time. Shifted out of its story position, spoken by a character we don’t yet know, the question becomes a challenge and warning to the viewer. As a film inviting us to unmask its own legerdemain,

The Prestige

could just as easily start with the question “Are you listening closely?”

As usual, both extensive viewing and intensive scrutiny will sharpen your capacity to notice the workings of film sound. You can get comfortable with the analytical tools we have suggested by asking several questions about a film’s sound:

- What sounds are present—music, speech, noise? How are loudness, pitch, and timbre used? Is the mixture sparse or dense? Modulated or abruptly changing?

- Is the sound related rhythmically to the image? If so, how?

- Is the sound faithful or unfaithful to its perceived source?

- Where

is the sound coming from? In the story’s space or outside it? Onscreen or offscreen? If offscreen, how is it shaping your response to what you’re seeing? - When

is the sound occurring? Simultaneously with the story action? Before? After? - How are the various sorts of sounds organized across a sequence or the entire film? What patterns are formed, and how do they reinforce aspects of the film’s overall form?

- For each of questions 1–6, what

purposes

are fulfilled and what

effects

are achieved by the sonic manipulations?

Practice at trying to answer such questions will familiarize you with the basic uses of film sound.

As always, it isn’t enough to name and classify. These categories and terms are most useful when we take the next step and examine how the types of sound we identify

function

in the total film.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

David Lewis Yewdall’s

Practical Art of Motion Picture Sound,

3d ed. (Boston: Focal Press, 2007), is an excellent overview and includes a very instructive DVD. A delightful essay on the development of film sound is Walter Murch’s “Sound Design: The Dancing Shadow,” in John Boorman et al., eds.,

Projections 4

(1995),

pp. 237

–51. The essay includes a behind-the-scenes discussion of sound mixing in

The Godfather.

Articles on particular aspects of sound recording and reproduction in Hollywood are published in

Recording Engineer/Producer

and

Mix.

See also Jeff Forlenza and Terri Stone, eds.,

Sound for Picture

(Winona, MN: Hal Leonard, 1993), and Tom Kenny,

Sound for Picture: Film Sound Through the 1990s

(Vallejo, CA: Mix Books, 2000). For many practitioners’ comments, see Vincent Lo Brutto,

Sound-on-Film: Interviews with Creators of Film Sound

(New York: Praeger, 1994). Walter Murch, Hollywood’s principal sound designer, explains many contemporary sound techniques in Roy Paul Madsen,

Working Cinema: Learning from the Masters

(Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1990),

p. 284

comes from this source, p. 000.

A useful introduction to the psychology of listening is Robert Sekuler and Randolph Blake,

Perception,

4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002). See as well R. Murray Schafe,

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World

(Rochester, VT: Destiny, 1994), and David Toop,

Ocean of Sound: Aether Talk, Ambient Sound and Imaginary Worlds

(London: Serpent’s Tail, 2001).

The psychologists’ term for our spontaneous merging of information from different senses is “cross-modal perception.” It has been observed in newborn babies and in children as young as four months. Joseph D. Anderson,

The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory

(Carbondale: University of Illinois Press, 1996),

chap. 5

, provides a compact introduction to how our bias toward cross-model pickup shapes our understanding of films.

Of all directors, Sergei Eisenstein has written most prolifically and intriguingly about sound technique. See in particular his discussion of audio-visual polyphony in

Non-Indifferent Nature,

trans. Herbert Marshall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987),

pp. 282

–354. (For his discussion of music, see below.) In addition, there are intriguing comments in Robert Bresson’s

Notes on Cinematography,

trans. Jonathan Griffin (New York: Urizen, 1977).

The artistic possibilities of film sound are discussed in many essays. See John Belton and Elizabeth Weis, eds.,

Film Sound: Theory and Practice

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1985); Rick Altman, ed.,

Sound Theory Sound Practice

(New York: Routledge, 1992); Larry Sider, Diane Freeman, and Jerry Sider, eds.,

Soundscape: The School of Sound Lectures 1998–2001

(London: Wallflower, 2003); “Sound and Music in the Movies,”

Cinéaste

21, 1–2 (1995): 46–80; and Jay Beck and Tony Grajeda, eds.,

Lowering the Boom: Critical Studies in Film Sound

(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008). Three anthologies edited by Philip Brophy have been published under the general title

CineSonic

(New South Wales: Australian Film Television and Radio School, 1999–2001).

The most prolific researcher in the aesthetics of film sound is Michel Chion, whose ideas are summarized in his

Audio Vision,

trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994). Sarah Kozloff has written extensively on speech in cinema; see

Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988) and

Overhearing Film Dialogue

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000). Lea Jacobs analyzes several dialogue patterns in “Keeping Up with Hawks,”

Style

32, 3 (Fall 1998): 402–26, from which our mention of accelerating and decelerating rhythm in

His Girl Friday

is drawn.

On sound and picture editing, see John Purcell,

Dialogue Editing for Motion Pictures: A Guide to the Invisible Art

(Boston: Focal Press, 2007). Dialogue overlap is explained in detail in Edward Dmytryk,

On Film Editing

(Boston: Focal Press, 1984),

pp. 47

–70.

As the

Letter from Siberia

extract suggests, documentary filmmakers have experimented a great deal with sound. For other cases, watch Basil Wright’s

Song of Ceylon

and Humphrey Jennings’s

Listen to Britain

and

Diary for Timothy.

Analyses of sound in these films may be found in Paul Rotha,

Documentary Film

(New York: Hastings House, 1952), and Karel Reisz and Gavin Millar’s

Technique of Film Editing

(New York: Hastings House, 1968),

pp. 156

–70.

Stephen Handzo provides a wide-ranging discussion of systems for recording and reproducing film sound in “A Narrative Glossary of Film Sound Technology,” in Belton and Weis,

Film Sound: Theory and Practice.

An updated survey is available in Gianluca Sergi,

The Dolby Era: Film Sound in Contemporary Hollywood

(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005). See also William Whittington,

Sound Design and Science Fiction

(Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007).

It’s long been assumed that cinema is predominantly a visual medium, with sound forming at best a supplement and at worst a distraction. In the late 1920s, many film aestheticians protected against the coming of talkies, feeling that synchronized sound spoiled a pristine mute art. In the bad sound film, René Clair claimed, “The image is reduced precisely to the role of the illustration of a phonograph record, and the sole aim of the whole show is to resemble as closely as possible the play of which it is the ‘cinematic’ reproduction. In three or four settings there take place endless scenes of dialogue which are merely boring if you do not understand English but unbearable if you do” (

Cinema Yesterday and Today

[New York: Dover, 1972],

p. 137

). Rudolf Arnheim asserted that “the introduction of the sound film smashed many of the forms that the film artists were using in favor of the inartistic demand for the greatest possible ‘naturalness’ (in the most superficial sense of the word)” (

Film as Art

[Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957],

p. 154

).

Today we find such beliefs silly, but we must recall that many early sound films relied simply on dialogue for their novelty; both Clair and Arnheim welcomed sound effects and music but warned against chatter. In any event, the inevitable reaction was led by André Bazin, who argued that a greater realism was possible in the sound cinema. See his

What Is Cinema?

vol. 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967). Even Bazin, however, seemed to believe that sound was secondary to the image in cinema. This view is also put forth by Siegfried Kracauer in

Theory of Film

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1965). “Films with sound live up to the spirit of the medium only if the visuals take the lead in them” (

p. 103

).

Today, many filmmakers and filmgoers would agree with Francis Ford Coppola’s remark that sound is “half the movie … at least.” One of the major advances of film scholarship of the 1970s and 1980s was the increased and detailed attention to the sound track.

On the transition from silent to sound film in American cinema, see Harry M. Geduld,

The Birth of the Talkies: From Edison to Jolson

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975); Alexander Walker,

The Shattered Silents

(New York: Morrow, 1979); chap. 23 of David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson,

The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1985); James Lastra,

Sound Technology in the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity

(New York: Columbia University Press, 2000); and Charles O’Brien,

Cinema’s Conversion to Sound: Technology and Film Style in France and the U.S.

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005). Douglas Gomery’s

The Coming of Sound

(New York: Rout-ledge, 2005) provides a U.S. industry history.

David Julyan’s discussion of scoring

The Prestige

can be found at

www.aintitcool.com/node/31031

.

Of all the kinds of sound in cinema, music has been the most extensively discussed. The literature is voluminous, and with a recent surge of interest in film composers, many more recordings of film music have become available.

A basic introduction to music useful for film study is William S. Newman,

Understanding Music

(New York: Harper, 1961). An up-to-date and detailed production guide is Fred Karlin and Rayburn Wright’s

On the Track: A Guide to Contemporary Film Scoring,

2d ed. (New York: Schirmer, 1990). Karlin’s

Listening to Movies

(New York: Routledge, 2004) offers a lively discussion of the Hollywood tradition.

The history of film scoring is handled in lively and unorthodox ways in Russell Lack,

Twenty-Four Frames Under: A Buried History of Film Music

(London: Quartet, 1997). For Hollywood-centered histories, see Roy M. Prendergast,

Film Music: A Neglected Art

(New York: Norton, 1977), and Gary Marmorstein,

Hollywood Rhapsody: Movie Music and Its Makers 1900–1975

(New York: Schirmer, 1997). Somewhat wider coverage is provided in Mervyn Cooke,

A History of Film Music

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008). See also Martin Miller Marks,

Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies 1895–1924

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), and Rick Altman,

Silent Film Sound

(New York: Columbia University Press, 2005). Contemporary film composers are interviewed in Michael Schelle,

The Score

(Los Angeles: Silman-James, 1999); David Morgan,

Knowing the Score

(New York: HarperCollins, 2000); and Mark Russell and James Young,

Film Music

(Hove, England; Rota, 2000).

The principal study of the theory of film music is Claudia Gorbman,

Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987). A highly informed, wide-ranging meditation on the subject is Royal S. Brown,

Overtones and Undertones: Reading Film Music

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994). Jonathan Romney and Adrian Wootton’s

Celluloid Jukebox: Popular Music and the Movies Since the 50s

(London: British Film Institute, 1995) is an enjoyable collection of essays. See also Chuck Jones, “Music and the Animated Cartoon,”

Hollywood Quarterly

1, 4 (July 1946): 364–70. A sampling of Carl Stalling’s amazing cartoon sound tracks (

p. 275

) is available on two compact discs (Warner Bros. 9-26027-2 and 9-45430-2).

Despite the bulk of material on film music, there have been fairly few analyses of music’s functions in particular films. The most famous (or notorious) is Sergei Eisenstein’s “Form and Content: Practice,” in

The Film Sense

(New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1942),

pp. 157

–216, which examines sound/image relations in a sequence from

Alexander Nevsky.

For sensitive analyses of film music, see Graham Bruce,

Bernard Herrmann: Film Music and Narrative

(Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1985); Kathryn Kalinak,

Settling the Score: Music and the Classical Hollywood Film

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992); Jeff Smith,

The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music

(New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); and Pamela Robertson Wojcik and Arthur Knight, eds.,

Sound-track Available: Essays on Film and Popular Music

(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001).

People beginning to study cinema may express surprise (or annoyance) that films in foreign languages are usually shown with subtitled captions translating the dialogue. Why not, some viewers ask, use dubbed versions of the films—that is, versions in which the dialogue has been rerecorded in the audience’s language? In many countries, dubbing is very common. (Germany and Italy have traditions of dubbing almost every imported film.) Why, then, do most people who study movies prefer subtitles?

There are several reasons. Dubbed voices usually have a bland studio sound. Elimination of the original actors’ voices wipes out an important component of their performance. (Partisans of dubbing ought to look at dubbed versions of English-language films to see how a performance by Katharine Hepburn, Orson Welles, or John Wayne can be hurt by a voice that does not fit the body.) With dubbing, all of the usual problems of translation are multiplied by the need to synchronize specific words with specific lip movements. Most important, with subtitling, viewers still have access to the original sound track. By eliminating the original voice track, dubbing simply destroys part of the film.

For a survey of subtitling practice, see Jan Ivarsson and Mary Carroll,

Subtitling

(Simrishamn, Sweden: TransEdit, 1998).

www.filmsound.org

The most comprehensive and detailed website on sound in cinema, with many interviews and links to other sites.

www.mixonline.com

The site for

Mix Magazine,

devoted to all aspects of film and video sound production. Offers many free articles and original web content.

widescreenmuseum.com/sound/sound01.htm

A review of the history of sound systems, illustrated with original documents.