B0041VYHGW EBOK (194 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The novelty and youthful vigor of these directors led journalists to nickname them

la nouvelle vague

—the

New Wave.

Their output was staggering. All told, the five central directors made 32 feature films between 1959 and 1966; Godard and Chabrol made 11 apiece. So many films must of course be highly disparate, but there are enough similarities for us to identify a broadly distinctive New Wave approach to style and form.

The most obviously revolutionary quality of the New Wave films was their casual look. To proponents of the carefully polished French

cinema of quality,

the young directors must have seemed hopelessly sloppy. The New Wave directors had admired the Neorealists (especially Rossellini) and, in opposition to studio filmmaking, took as their mise-en-scene actual locales in and around Paris. Shooting on location became the norm

(

12.46

).

Similarly, glossy studio lighting was replaced by available light and simple supplemental sources. Few postwar French films would have shown the dim, grimy apartments and corridors featured in

Paris Belongs to Us.

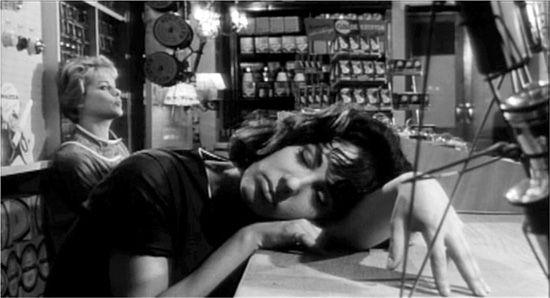

12.46

Les Bonnes femmes

: while a serial killer stalks them, two of the heroines sit idly at work. Like many New Wave directors, Claude Chabrol followed the Neorealists in shooting on locations like this drab appliance shop.

Cinematography changed, too. The New Wave camera moves a great deal, panning and tracking to follow characters or trace out relations within a locale. Furthermore, shooting cheaply on location demanded flexible, portable equipment. Fortunately, Eclair had recently developed a lightweight camera that could be handheld. (That the Eclair had been used primarily for documentary work accorded perfectly with the realistic mise-en-scene of the New Wave.) New Wave filmmakers were intoxicated with the new freedom offered by the handheld camera. In

The 400 Blows,

the camera explores a cramped apartment and rides a carnival centrifuge. In

Breathless,

the cinematographer held the camera while seated in a wheelchair to follow the hero along a complex path in a travel agency’s office (11.36).

One of the most salient features of New Wave films is their casual humor. These young men deliberately played with the medium. In Godard’s

Band of Outsiders,

the three main characters resolve to be silent for a minute, and Godard dutifully shuts off

all

the sound. In Truffaut’s

Shoot the Piano Player,

a character swears that he’s not lying: “May my mother drop dead if I’m not telling the truth.” Cut to a shot of an old lady keeling over.

Along with humor came esoteric references to other films, Hollywood or European. There are homages to admired auteurs: Godard characters allude to

Johnny Guitar

(Ray),

Some Came Running

(Minnelli), and “Arizona Jim” (from Renoir’s

Crime of M. Lange

). In

Les Carabiniers,

Godard parodies Lumière, and in

Vivre sa vie,

he visually quotes

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc

(

12.47

,

12.48

).

Hitchcock is frequently cited in Chabrol’s films, and Truffaut’s

Les Mistons

re-creates a shot from a Lumière short. Such citations, the New Wave directors felt, acknowledged that cinema, like literature and painting, had lofty traditions that could be honored.

12.47 In

Vivre sa vie,

a clip from Dreyer’s

The Passion of Joan of Arc

…

12.48 … helps dramatize the heroine’s feelings as she watches it.

New Wave films also pushed further the Neorealist experimentation with plot construction. In general, causal connections became quite loose. Is there actually a political conspiracy going on in

Paris Belongs to Us?

Why is Nana shot at the end of

Vivre sa vie?

In

Shoot the Piano Player,

the first sequence consists mainly of a conversation between the hero’s brother and a man he accidentally meets on the street; the latter tells of his marital problems at some length, even though he has nothing to do with the film’s narrative.

Moreover, the films often lack goal-oriented protagonists. The heroes may drift aimlessly, engage in actions on the spur of the moment, or spend their time talking and drinking in a café or going to movies. New Wave narratives often introduce startling shifts in tone, jolting our expectations. When two gangsters kidnap the hero and his girlfriend in

Shoot the Piano Player,

the whole group begins a comic discussion of sex. Discontinuous editing further disturbs narrative continuity; this tendency reaches its limit in Godard’s jump cuts (6.137, 6.138, 11.39, 11.40).

Perhaps most important, the New Wave film typically ends ambiguously. We have seen this already in

Breathless

(

pp. 410

–411). Antoine in

The 400 Blows

reaches the sea in the last shot, but as he moves forward, Truffaut zooms in and freezes the frame, ending the film with the question of where Antoine will go from there (3.8). In Chabrol’s

Les Bonnes Femmes

and

Ophelia,

in Rivette’s

Paris Belongs to Us,

and in nearly all the work of Godard and Truffaut in this period, the looseness of the causal chain leads to endings that remain defiantly open and uncertain.

Despite the demands that the films placed on the viewer and despite the critical rampages of the filmmakers, the French film industry wasn’t hostile to the New Wave. The decade 1947–1957 had been good to film production: the government supported the industry through enforced quotas, banks had invested heavily, and there was a flourishing business of international coproductions. But in 1957, cinema attendance fell off drastically, chiefly because television became more widespread. By 1959, the industry was in a crisis. The independent financing of low-budget films seemed to offer a good solution. New Wave directors shot films much more quickly and cheaply than did reigning directors. Moreover, the young directors helped one another out and thus reduced the financial risk of the established companies. Thus the French industry supported the New Wave through distribution, exhibition, and eventually production.

Indeed, it is possible to argue that by 1964, although each New Wave director had his or her own production company, the group had become absorbed into the film industry. Godard made

Le Mépris

(

Contempt,

1963) for a major commercial producer, Carlo Ponti; Truffaut made

Fahrenheit 451

(1966) in England for Universal; and Chabrol began turning out parodies of James Bond thrillers.

Dating the exact end of the movement is difficult, but most historians select 1964, when the characteristic New Wave form and style had already become diffused and imitated (by, for instance, Tony Richardson in his 1963 English film

Tom Jones

). Certainly, after 1968, the political upheavals in France drastically altered the personal relations among the directors. Chabrol, Truffaut, and Rohmer became firmly entrenched in the French film industry, whereas Godard set up an experimental film and video studio in Switzerland, and Rivette began to create narratives of staggering complexity and length (such as

Out One,

originally about 12 hours long). By the mid-1980s, Truffaut had died, Chabrol’s films were often unseen outside France, and Rivette’s output had become esoteric. Rohmer retained international attention with his ironic tales of love and self-deception among the upper-middle class (

Pauline at the Beach

[1982] and

Full Moon over Paris

[1984]). Godard continued to attract notoriety with such films as

Passion

(1981) and his controversial retelling of the Old and New Testaments,

Hail Mary

(1983). In 1990, he released an elegant, enigmatic film ironically entitled

Nouvelle vague,

one that bears little relationship to the original tendency. In retrospect, the New Wave not only offered several original and valuable films but also demonstrated that renewal in the film industry could come from talented, aggressive young people inspired in large part by the sheer love of cinema.

Midway through the 1960s, the Hollywood industry seemed very healthy, with blockbusters such as

The Sound of Music

(1965) and

Dr. Zhivago

(1965) yielding huge profits. But soon problems arose. Expensive studio projects failed miserably. Television networks, which had paid high prices to broadcast films after theatrical release, stopped bidding for pictures. American movie attendance flattened out at around 1 billion tickets per year (a figure that, despite home video, remained constant until the early 1990s). By 1969, Hollywood companies were losing over $200 million annually.

Producers fought back. One strategy was to produce counterculture-flavored films aimed at young people. The most popular and influential were Dennis Hopper’s low-budget

Easy Rider

(1969) and Robert Altman’s

M

*

A

*

S

*

H

(1970). By and large, however, other “youthpix” about campus revolution and unorthodox lifestyles proved disappointing at the box office. What did help lift the industry’s fortunes were films aimed squarely at broader audiences. The most successful were Francis Ford Coppola’s

The Godfather

(1972); William Friedkin’s

The Exorcist

(1973); Steven Spielberg’s

Jaws

(1975) and

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

(1977); John Carpenter’s

Halloween

(1978); and George Lucas’s

American Graffiti

(1973),

Star Wars

(1977), and

The Empire Strikes Back

(1980). In addition, films by Brian De Palma (

Obsession,

1976) and Martin Scorsese (

Taxi Driver,

1976;

Raging Bull,

1980) attracted critical praise.

These and other directors came to be known as the movie brats. Instead of coming up through the ranks of the studio system, most had gone to film schools. At New York University, the University of Southern California, and the University of California at Los Angeles, they had not only mastered the mechanics of production but also learned about film aesthetics and history. Unlike earlier Hollywood directors, the movie brats often had an encyclopedic knowledge of great movies and directors. Even those who did not attend film school were admirers of the classical Hollywood tradition.

As had been the case with the French New Wave, these film-buff directors produced some personal, highly self-conscious films. The movie brats worked in traditional genres, but they also tried to give them an autobiographical coloring. Thus

American Graffiti

was not only a teenage musical but also Lucas’s reflection on growing up in central California in the 1960s. Martin Scorsese drew on his youth in New York’s Little Italy for his crime drama

Mean Streets

(1973;

12.49

). Coppola imbued both

Godfather

films with a vivacious and melancholy sense of the intense bonds within the Italian American family. Paul Schrader poured his own obsessions with violence and sexuality into his scripts for

Taxi Driver

and

Raging Bull

and the films he directed, such as

Hard Core

(1979).