B0041VYHGW EBOK (85 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

3.

Patterns of mobile framing

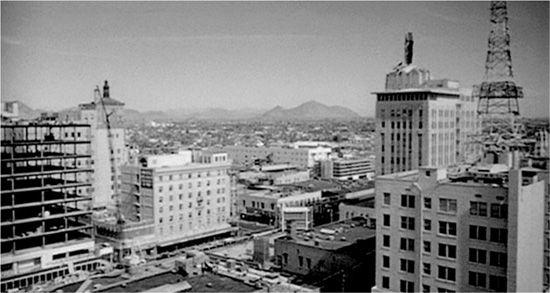

The mobile frame can create its own specific motifs within a film. For example, Hitchcock’s

Psycho

begins and ends with a forward movement of the frame. In the film’s first three shots, the camera pans right and then zooms in on a building in a cityscape

(

5.154

).

Two forward movements finally carry us under a window blind and into the darkness of a cheap hotel room

(

5.155

–

5.157

).

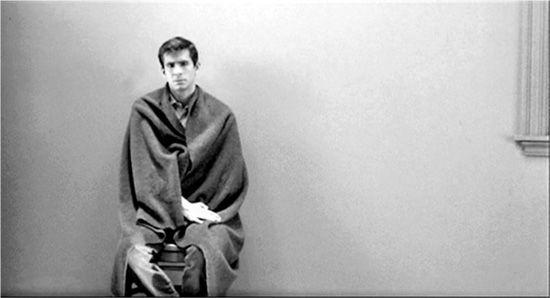

The camera’s movement inward, the penetration of an interior, is repeated throughout the film, often motivated as a subjective point of view as when various characters move deeper and deeper into Norman Bates’s mansion. The next-to-last shot of the film shows Norman sitting against a blank white wall, while we hear his interior monologue

(

5.158

).

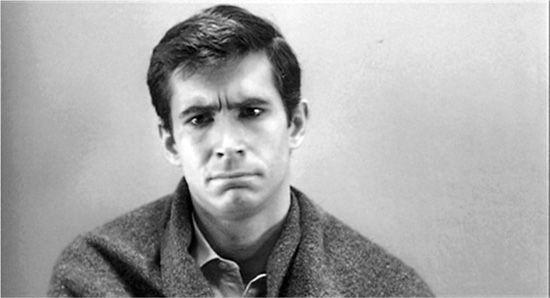

The camera again moves forward into a close-up of his face

(

5.159

).

This shot is the climax of the forward movement initiated at the start of the film; the film has traced a movement into Norman’s mind. Another film that relies heavily on a pattern of forward, penetrating movements is

Citizen Kane,

which depicts the same inexorable drive toward the revelation of a character’s secret.

5.154 The opening shot of

Psycho.

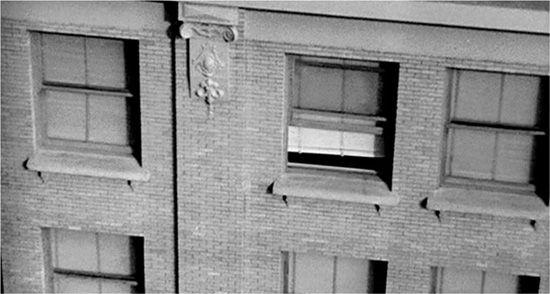

5.155 The second shot concentrates on one building …

5.156 … as the camera moves lower and closer to a window …

5.157 … and reveals the heroine and her boyfriend in a lunchtime tryst.

5.158

Psycho

’s next-to-last shot begins at a distance from Norman …

5.159 … and moves in so that we see his expression as we hear his thoughts.

“One thing I hate in films is when the camera starts circling characters. If three people are sitting at a table talking, you’ll often see the camera circling them. I can’t explain why, but I find it totally fake.”

— Takeshi Kitano, director,

Sonatine

Other kinds of movements can repeat and develop across a film. Max Ophuls’s

Lola Montès

uses both 360° tracking shots and constant upward and downward crane shots to contrast the circus arena with the world of Lola’s past. In Michael Snow’s ↔ (usually called

Back and Forth

), the constant panning to and fro across a classroom, Ping-Pong fashion, determines the basic formal pattern of the film. It comes as a surprise when, near the very end, the movement suddenly becomes a repeated tilting up and down. In these and many other films, the mobile frame sets up marked repetitions and variations.

By way of summary, we can look at two contrasting films that illustrate possible relations of the mobile frame to narrative form. One uses the mobile frame in order to strengthen and support the narrative, whereas the other subordinates narrative form to an overall frame mobility.

Jean Renoir’s

Grand Illusion

is a war film in which we almost never see the war. Heroic charges and doomed battalions, the staple of the genre, are absent. World War I remains obstinately offscreen. Instead, Renoir concentrates on life in a German POW camp to suggest how relations between nations and social classes are affected by war. The prisoners Maréchal and Boeldieu are both French; Rauffenstein is a German officer. Yet the aristocrat Boeldieu has more in common with Rauffenstein than with the mechanic Maréchal. The film’s narrative form traces the death of the Boeldieu-Rauffenstein upper class and the precarious survival of Maréchal and his pal Rosenthal—their flight to Elsa’s farm, their interlude of peace there, and their final escape back to France and presumably back to the war.

Within this framework, camera movement has several functions, all directly supportive of the narrative. First, and most typical, is its tendency to adhere to figure movement. When a character or vehicle moves, Renoir often pans or tracks to follow. The camera follows Maréchal and Rosenthal walking together after their escape; it tracks back when the prisoners are drawn to the window by the sound of marching Germans below. But it is the movements of the camera

independent

of figure movement that make the film more unusual.

When the camera moves on its own in

Grand Illusion,

we are conscious of it actively interpreting the action, creating suspense or giving us information that the characters do not have. For example, in one scene, a prisoner is digging in an escape tunnel and tugs a string signaling that he needs to be pulled out

(

5.160

).

Independent camera movement builds suspense by showing that the other characters have missed the signal and do not realize that he is suffocating

(

5.161

,

5.162

).

Camera movement thus helps create a somewhat unrestricted narration.

5.160 A can used as a signal is initially seen sitting on a shelf …

5.161 … then is pulled over. It lands on a pillow and so makes no sound …

5.162 … and the camera pans left to reveal that the characters have not noticed it.