B0041VYHGW EBOK (96 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

6.28

The Birds:

shot 35.

6.29

The Birds:

shot 36.

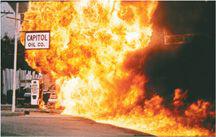

6.30

The Birds:

shot 37.

6.31

The Birds:

shot 38.

6.32

The Birds:

shot 39.

6.33

The Birds:

shot 40.

In graphic terms, Hitchcock has exploited two possibilities of contrast. First, although each shot’s composition centers the action (Melanie’s head, the flaming trail), the movements thrust in different directions. In shot 31, Melanie looks to the lower left, whereas in shot 32, the fire moves to the upper left. In shot 33, Melanie is looking down center, whereas in shot 34, the flames still move to the upper left, and so on.

More important—and what makes the sequence impossible to recapture on the printed page—is a crucial contrast of mobility and stasis. The shots of the flames present movement of both the subject (the flames rushing along the gas) and the camera (which pans to follow). But each shot of Melanie could be a still photograph, since each one is absolutely static. She does not turn her head in any shot, and the camera does not track in or away from her. We must infer the progress of her attention. By making movement conflict with countermovement and with stillness, Hitchcock has powerfully exploited the graphic possibilities of editing.

Each shot, being a strip of film, is of a certain length, measured in frames, feet, or meters. And the shot’s physical length corresponds to a measurable duration onscreen. As we know, at sound speed, 24 frames last one second in projection. A shot can be as short as a single frame, or it may be thousands of frames long, running for many minutes when projected. Editing thus allows the filmmaker to determine the duration of each shot. When the filmmaker adjusts the length of shots in relation to one another, she or he is controlling the

rhythmic

potential of editing.

Cinematic rhythm as a whole derives not only from editing but from other film techniques as well. The filmmaker relies on movement in the mise-en-scene, camera position and movement, the rhythm of sound, and the overall context to determine the editing rhythm. Nevertheless, the patterning of shot lengths contributes considerably to what we intuitively recognize as a film’s rhythm.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Some analysts study rhythm in film by calculating average shot lengths across sequences of films. For more on that, see “My name is David, and I’m a frame-counter,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=230

.

Sometimes the filmmaker will use shot duration to create a stressed, accented, moment. In one sequence of

The Road Warrior,

a ferocious gang member butts his head against that of a victim. At the moment of contact, director George Miller cuts in a few frames of pure white. The result is a sudden flash that suggests violent impact. Alternatively, a shot’s duration can be used to deaccentuate an action. During test screenings of

Raiders of the Lost Ark,

Steven Spielberg discovered that after Indiana Jones shoots the gigantic swordsman, several seconds had to be added to allow the audience’s reaction to die down before the action could resume.

More commonly, the rhythmic possibilities of editing emerge when several shot lengths form a discernible pattern. A steady beat can be established by making all of the shots approximately the same length. The filmmaker can also create a dynamic pace. Lengthening shots can gradually slow the tempo, while successively shorter shots can accelerate it.

Consider how Hitchcock handles the tempo of the first gull attack in

The Birds.

Shot 1, the medium shot of the group talking (

6.5

), consumes almost a thousand frames, or about 41 seconds. But shot 2 (

6.6

), which shows Melanie looking out the window, is much shorter—309 frames (about 13 seconds). Even shorter is shot 3 (

6.7

), which lasts only 55 frames (about 2⅓ seconds). The fourth shot (

6.8

), showing Melanie joined by Mitch and the Captain, lasts only 35 frames (about 1½ seconds). Clearly, Hitchcock is accelerating the pace at the beginning of what will be a tense sequence.

In what follows, Hitchcock makes the shots fairly short but subordinates the length of the shot to the rhythm of the dialogue and the movement in the images. As a result, shots 5–29 (not shown here) have no fixed pattern of lengths. But once the essential components of the scene have been established, Hitchcock returns to strongly accelerating cutting.

In presenting Melanie’s horrified realization of the flames racing from the parking lot to the gas station, shots 30–40 (

6.23

–

6.33

) climax the rhythmic intensification of the sequence. As the description on

page 228

shows, after the shot of the spreading flames (shot 30,

6.23

), each shot decreases in length by 2 frames, from 20 frames (⅘ of a second) to 8 frames (⅓ of a second). Two shots, 38 and 39, then punctuate the sequence with almost identical durations (a little less than 1½ seconds apiece). Shot 40 (

6.33

), a long shot that lasts over 600 frames, functions as both a pause and a suspenseful preparation for the new attack. The scene’s variations in rhythm alternate between rendering the savagery of the attack and generating suspense as we await the next onslaught.

“I noticed a softening in American cinema over the last twenty years, and I think it’s a direct influence of TV. I would even say that if you want to make movies today, you’d be better off studying television than film because that’s the market. Television has diminished the audience’s attention span. It’s hard to make a slow, quiet film today. Not that

I

would want to make a slow, quiet film anyway!”— Oliver Stone, director

We have had the luxury of counting frames on the actual strip of film. The theater viewer cannot do this, but she or he does feel the shifting tempo in this sequence because of the changing shot durations. In general, by controlling editing rhythm, the filmmaker controls the amount of time we have to grasp and reflect on what we see. A series of rapid shots, for example, leaves us little time to think about what we’re watching. In the

Birds

sequence, Hitchcock’s editing impels the viewer’s perception to move at a faster and faster pace. Quickly grasping the progress of the fire and understanding Melanie’s changes in position become essential factors in the rising excitement of the scene.

Hitchcock is not, of course, the only director to use rhythmic editing. Its possibilities were initially explored by such directors as D. W. Griffith (especially in

Intolerance

) and Abel Gance. In the 1920s, the French Impressionist filmmakers and the Soviet Montage school explored the rhythmic possibilities of strings of short shots (

pp. 463

–466,

467

–469). When sound films became the norm, pronounced rhythmic editing survived in dramas such as Lewis Milestone’s

All Quiet on the Western Front

and in musical comedies and fantasies such as René Clair’s

À Nous la liberté

and

Le Million,

Rouben Mamoulian’s

Love Me Tonight,

and Busby Berkeley’s dance sequences in

42nd Street

and

Footlight Parade.

“[In editing

The Dark Knight

for both 35mm and Imax presentation], we needed to extensively test to ensure that the cuts were not so quick that the audience would get disoriented, looking at that Imax screen, and at the same time not interfere with the pace of the standard cinema version.”— Lee Smith, editor