B004YENES8 EBOK (16 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

“Well,” she said, groping for some semblance of dignity, “this is silly.”

It was only a little after that when I told her what I had said to Tyne Daly — perhaps a year before: “You may add salt to my tomato juice. You may add pepper, or Tabasco, or vodka to my tomato juice; but you may not piss in my tomato juice. That’s what went wrong tonight.” In case the point was missed, I quickly added, “You were pissing in my tomato juice.”

My leading lady understood. It was territorial. Sharon is a child of the Hollywood community and knows better than most what is required of a pro. She apologized for the whole scene, and I promised to try to be more attentive to her requests.

“Provided I don’t make them in front of the crew,” she said, filling in the obvious blank.

“You got it,” I replied.

I too had learned something that night. Play out these confrontations to their conclusion. Do not put them on hold. Deal with them frontally, and immediately, for they do not get better by themselves. Unfortunately, something I had put on hold with Tyne Daly, in the days before this learned lesson, would now come to the fore.

For Christmas I had gifted each of the women with an 18-karat gold police whistle and chain from Tiffany. Tyne returned hers to me with a note written on the back of a title page from one of our scripts, as if the whole thing was unworthy of stationery. I had, she wrote, betrayed her, and so she could not accept my “token of friendship.”

The deal over billing continued to fester, and Tyne remained volatile. One day she was “demeaned” by the work, the poor quality of directors, her “honor gone”; later that same afternoon she might stop by my office, overflowing with enthusiasm for what it was we were attempting to do, the “journey”, our “art”. This was not a crazy person, far from it. She was exhausted from a near-impossible schedule at work, the everyday demands of family, and—let us not forget—she is an actress.

Being the star of a television series was, I believe, never Tyne’s dream. I had seduced her into that life. In fact, I think, being the star of anything was fairly antithetical to who Tyne Daly is and/or wants to be, on the one hand. On the other hand, she can be a pure diva of operatic proportions.

Within days of the returned-whistle incident, Tyne mentioned that she and Sharon wished I would reinstate the practice of calling them at home after the network airing of the show each Monday night. I had stopped phoning the two women when I finally tired of getting beaten up by their lack of acceptance of the work, hating me, or missing their close-ups.

“

Deeper, richer, fuller, better never stops. It is a constant war against time and limited funds and the mediocrity of most of us,”

I wrote in my diary about that time. I went on with the entry:

“Tyne and I made an agreement: When we finally make a good episode, we will all quit. I tell her it will probably take several years of practice to accomplish this

.”

Another note from my diary, referring to Sharon and Tyne, sums it up: “

January 28, 1983: They are tough and demanding … I love them

.”

To the men on

Cagney & Lacey

, I had gifted sterling silver police whistles. It prompted my friend, Sidney Clute, to ask what he could possibly give me in return. It seemed, to him, I had everything. I told him that what I really wanted was for him to take care of himself and to remain healthy and happy on our series for years to come. He began to weep as we hugged each other. We both feared that the backaches he had been experiencing were the return of his cancer. My once-robust tennis pal was now becoming very frail.

Next it was Steve Brown and Terry Louise Fisher presenting me with a problem. When I met them on

This Girl for Hire

, they had been living together. That phase of their lives had ended, and now, with

Cagney & Lacey

, they were attempting to work together for the first time without personal involvement. To hear them tell it, it was not going well; still, they were determined to finish the season and fulfill their contractual obligations. They just wanted me to be aware of it, lest things got testy. This information was given to me quite gratuitously (as if I might give a shit), and there was also some reference to the possibility of my occasionally serving them as padre, to which, if memory serves, I reluctantly agreed.

And to think people wonder what a producer does.

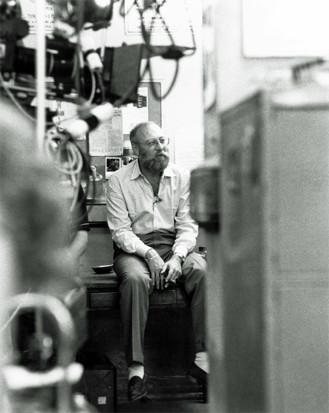

The sun glaring off my glasses in the parking lot outside of Lacey Street indicates this was an early morning photo. That, plus the warm sweater I am wearing, would tell me it was probably winter time in southern California. Other than that, I remember nothing and deny everything.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

A photo taken by then-

C&L

PA (production assistant) Stacy Codikow. This picture, in which Sharon and Tyne share the spotlight with Barbara’s mother (Jo Corday, in character as the bag lady Josie on the set at Lacy Street), wound up in

People

magazine: A nice coup for Ms. Codikow, as well as our show. Barbara’s mom was pleased, too.

Photo: Carole R. Smith Personal Collection

On the set of the 14th Precinct at Lacy Street.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

I have never known Sharon to do a crossword puzzle, although both she and Tyne are regular answers in

The New York Times

and other such publications. This must have been her “in character.” It certainly is on the set. Her desk and the holding pen in the background. Note the cup in the foreground. Cagney used hers for a pencil holder, preferring to have her coffee from a Styrofoam cup. Tyne’s Mary Beth Lacey drank from hers.

Photo: Courtesy of MGM

Chapter 19

WHAT CAGNEY REALLY WANTS …

The pressure on Brown & Fisher and their first script for

Cagney & Lacey

was considerable. It would be the first work from the new team we would see, and it would be scrutinized as few others.

29

In it, the team went to their strength: Brown’s excellent sense of story structure and Ms. Fisher’s understanding of the legal bureaucracy (something she would eventually exploit to its fullest by co-creating, with Steven Bochco,

L.A. Law

). Terry had been a lawyer with the district attorney’s office in Los Angeles a few years before. We all were to benefit from this period of civil service.

The day after this episode aired, Harvey Shephard told me that, like everyone else, he was concerned about the departure of April Smith and Bob Crais, but that “… last night’s episode was top drawer … one of the season’s best.” It was a most welcome congratulations. He added, at a lunch a few days later, that while watching the episode, his wife, Dale, stated that if he canceled

Cagney & Lacey

the marriage was over. That Harvey and Dale Shephard have one of the more stable relationships in all of Hollywood gave me reason to smile.

“Open and Shut Case” was quickly followed by another Brown & Fisher teleplay, “Date Rape.” Here, too, there was nearly a unanimous reaction: almost everyone hated it. Corday began the criticism, followed quickly by Tony Barr’s office, then the broadcast standards department at CBS, then Dick Rosenbloom, and, finally, Tyne Daly, who had been beating on the writing staff for weeks until they were punchy. At the end of our cast’s initial table reading of this latest tome, Tyne tossed the script across the room saying, “This is garbage.”

I did not agree. I liked the script, and so did director John Patterson. We were joined in supporting Steve and Terry’s effort by Sharon Gless, but I suspected her endorsement was more because of the material’s raunchy quality than because of the very nice political statement the piece made in its thematic presentation of the tastelessness of sexual humor in the workplace. The police drama on which all of this was hung was an acquaintance rape, which brought its share of insensitive, deprecating snickers from the men in the squad room.

That all the naysayers were successfully confronted and that the episode became one of our better ones is not as significant as a particular moment on the set of this specific production.

The scene to which I refer took place in the squad room. A discussion was heating up between the Lacey character and the men of the 14th regarding what does, and does not, constitute rape. Samuels, the squad’s commanding officer, enters the fray with the observation that his wife’s favorite movie is

Gone with the Wind

.

“ ‘So romantic,’ Thelma used to say.” And then Samuels adds, “so how come when Rhett Butler carries Scarlett O’Hara upstairs it’s romance, and with some other poor slob it’s rape?”

Lacey’s rejoinder is swift and to the point, and she states it in front of everyone: “Begging your pardon, Lieutenant, but if you don’t know the difference between rape and romance, you’ve got a serious problem.” With that she exits the squad room.

Samuels is taken aback, and Desk Sergeant Coleman refers to Lacey with the thematically proper sexist tension reliever: “Her time of the month, or what?”

This was not the Cagney character, turning a sexist comment on its head the way it was used in the original Avedon teleplay; this was the all-too-typical male “explanation” for anything to do with a female that a guy may find inexplicable.

At any rate, at this point Sharon spoke up. She wanted her character to say something. To her, Cagney was John Wayne in a skirt, and she felt she should come to the defense of her partner.

It should probably be pointed out that up to this juncture the entire action of the three-plus-page sequence had taken place around the desks of the two women, with the blonde detective not contributing to the debate.

This was in the early days in the overall history of the series; we were still all getting to know each other. By example, it provides an opportunity to make several points, not the least of which is who does what, along with some potential responses during such a crisis moment.

The scene in question had been lit and rehearsed; hours had passed in the process. The sequence was about to be committed to film, and the star wanted a change.

“Get me a writer down here,” the director might shout, believing it’s all working beautifully, and, if he can just get this scene, along with its necessary coverage in the can, there’s a shot at maintaining the day’s schedule of eight to ten pages.

The writer (in this case, God help me, writer-producer) is summoned. “Think fast,” she, he, or they, might say to themselves. “Don’t be defensive; it’s only one line. The problem is, it’s got to be a beaut, a real Clint Eastwood-topper …”

The crew stands around and waits.

That’s the setup, and that’s the cast of characters—all well-intentioned, hardworking people. The actor-star who wants something to say, the director who thinks it’s a good idea (but just come up with it fast so we can shoot), and the writer who is so conditioned to taking notes he or she is automatically doing what is requested, for to refuse might:

(a)Delay production—the consequences of which are usually foreign to this person of strong literary bent, but known to be undesirable.

(b)Bring stinging accusations concerning their egotistic unwillingness to change anything from the way they wrote it in the first place, precipitating, yet again, an unfavorable comparison to William Shakespeare.

Besides—it’s not a bad idea. The star should have a topper—right?

And that is why you need a producer: a real one; someone who understands the actor, the material, the characters, the production schedule, and the editorial concept of how the scene will ultimately be put together.

I disagreed with Gless and leaned in close, excluding those around us, to explain my point of view. “Let me tell you what Christine Cagney wants,” I began, gaining her undivided attention.

“What Cagney wants—more than anything—is to be in the club, to be one of the guys. It’s much more important to her than saying or doing the right thing, or even coming to the defense of her partner. So, not only do I not want you to say anything here, but after Coleman’s line about her time of the month, I’m going to cut to a reactive close-up of you to emphasize the fact that you, indeed, say nothing.”

Sharon’s eyes lit up as if she were a child on Christmas morning as she referred to the character about whom she still was learning. “Boy,” Sharon nodded, “she’s a real cooze

30

, isn’t she?”

“Well, let’s say she’s flawed.” I smiled in reply. It was an important moment for us all. Only weeks before, in our episode “Jane Doe #37,” Sharon was unable to relate to—and refused to play—what she perceived as weakness in her character. Now she got it; the epiphany was fundamental to so much of what we would do in the future.

It would be the cornerstone of what Sharon would bring to the series. Her willingness to henceforth play a character with real flaws rather than a conventional TV heroine, plus her unmatched likability, gave us a license few in television had ever had before. Cagney could be ruthless, self-serving, ambitious. She could lie or cheat, flirt for gain, or be insensitive to others and—as Sharon would play it—we would forgive her.

For a picture maker, it was a remarkable asset. Four and three-quarter reels of Cagney pushing, manipulating, and generally being a shit. In one episode, her machinations even resulted in an informant’s death. One silent moment at the end: Sharon’s Cagney with a tear in her eye. Our hearts would be broken, and all would be forgiven. She didn’t even say, “I’m sorry.” It didn’t matter. It was a very fun thing to watch.

Sharon would never concede our point about Peter Lefcourt’s script of “Jane Doe” (even after the script itself received our first Writers Guild award nomination), but she never again hesitated to play full tilt what we would give her in the way of a social or psychological handicap.

Tyne meanwhile had come back from a two-day holiday with a complaint. The workload at home, with two adolescent daughters and a husband, was as great as it was at Lacy Street—only at home no one looked after her as our comfort squad

31

did for her at our factory. The discussion led to our episode “Burnout,” and to Ms. Daly’s first

Emmy

Award.