B006OAL1QM EBOK (18 page)

Authors: Heinrich Fraenkel,Roger Manvell

The brightest flame was, of course, Hitler himself. “The Leader is great just because he follows one sole end with dauntless tenacity, and is ready to sacrifice everything for it.”

38

One night at the Kaiserhof Hotel Goebbels spoke to his colleagues about nobility. Nobility has value “only if its privileges are based upon greater duties towards the nation”. In any case, as Goebbels put it, “the Movement had grown under divine protection, and all that was, has had to be, so that we might reach the point where we are now”.

39

One could not say fairer than that.

Goebbels himself, both consciously and unconsciously, draws his own self-portrait in this undoubtedly much edited book. There are, of course, none of the revealing glimpses of his private life such as those set down by his own hand in the diaries of 1925-26. This is the public Goebbels, the man in the Nazi mask. He represents himself as boundlessly energetic, ceaselessly efficient, continuously overworked, a relentless campaigner for Hitler. Much of this we must admit to be true, however coloured the self-portrait is by Goebbels' vanity. At the time the published diary begins he had just got married, and Magda is represented as never very far from his thoughts. Hitler, as we have seen, was a constant visitor, talking into the night. (“It is delightful to be alone with him.”) Magda gave birth to a daughter, Helga, on 1st September 1932. But by the following Christmas (“The feast of the Divine Love is drawing near,” writes Goebbels) Magda is seriously ill in hospital. “A sad Christmas! My heart is full of grief. The only consolation is that little Harald is with me.”

40

Harald was Magda's son by her first husband. “We light up a Christmas tree, and have a sad little Christmas by ourselves…. The Leader has sent a very kind telegram to the hospital. He, too, will be quite alone on Christmas Eve.” After this he plunged into the Lippe election campaign, keeping in touch with the hospital as best he could by telephone. Magda did not return home until 1st February. Hitler visited her in hospital, and sent her flowers.

With these occasional glimpses of a domesticated Goebbels we have to remain content. He likes to refer to the relaxation of music after the long day's work—"Music lifts us out of the humdrum of every day, and makes us feel, afresh, the higher inspiration of our work.”

41

Goebbels had, after all, as the Minister responsible for culture as well as for propaganda by the time his diary was published, to maintain the correct kind of self-portrait before the German public. Wagner, Hitler's favourite composer, always stimulated him. Wagner's kind of music could so easily be linked with German nationalism. There are many references in the diary to Wagner's “eternal genius”. After hearing a performance of The

Meistersinger

Goebbels writes:

The giant Wagner stands so high above all modern musical nonentities that it is unworthy of his genius for them to be compared to him. As the great ‘Awake’ Chorus begins you feel the stimulation in your blood. Germany, too, will soon feel the same, and be called to an awakening.

42

But the main picture of himself that he presents in the diary is of the worker and strategist, tirelessly pursuing campaign after campaign. “We live for nothing but this drive for success and political achievement.”

43

Once more eternally on the move. Work has to be done standing, walking, driving, flying. The most urgent conferences are held on the stairs, in the hall, at the door, or on the way to the station. It nearly drives one out of one's senses. One is carried by train, motor-car and aeroplane criss-cross through Germany. One arrives at a town half an hour before the beginning of a meeting or sometimes even later, goes up to the platform and speaks.

44

“I am so dead tired and exhausted that I can hardly stand,” he writes elsewhere. And with a suitable touch of pathos to win the admiration of the reader relaxed in his armchair: “I

must

break off a little just for an hour's rest.” Even when he is ill with a high fever he presses on. “I give an address in each of the two halls. The audience has no idea how bad I feel.”

With Goebbels the pose is never very far from the man. Much of what he claims for himself is just, but he is so vain of his achievements that he basks almost indecently in the sunshine of his self-assumed virtues. No one questions his ability, though he was, like other very able men in politics, to miscalculate sometimes, more especially when he came to power. No one questions his energy, though if his self-interest was not fired he could be listless and lazy, as he admits in his earlier writings. His loyalty to Hitler was without doubt linked subconsciously to this same instinct to gain power and glory for himself, but even so there is no need to question the sincerity of his devotion as far as it goes. Hitler was a success partly through Goebbels' own intelligent promotion of him. His success was a measure of Goebbels' own power. Loyalty to Hitler was loyalty to himself.

Goebbels' greatest self-appreciation lay in his talents as a speaker. He knew he was good, and he was good. There are constant, revealing references to his experiences as agitator and orator. “Am received by hooting. When I leave there is either silence or applause.”

45

But there was no pleasure to equal the enjoyment of a completely successful performance before an already excited audience in the Sport-palast.

To address such an audience is a real treat. One forgets time and space. I speak for two and a half hours or more, and launch attack after attack against the Government. It all ends with prolonged cheering. A strange experience to leave the seething ocean of humanity at the Sportpalast, drive through the wildly cheering crowd in the Pots-damerstrasse, and find oneself sitting in the quiet of one's home a few minutes later. One arrives late and tired, and tumbles into bed like the dead.

46

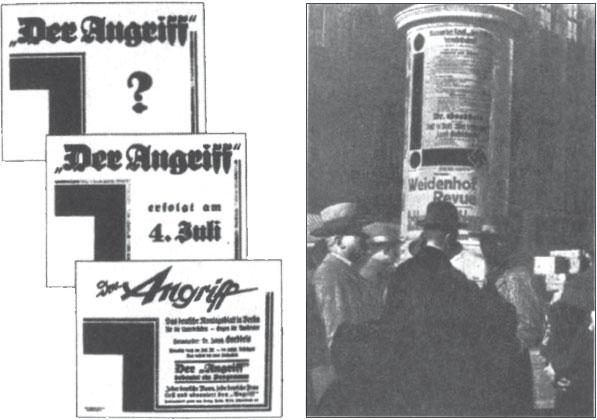

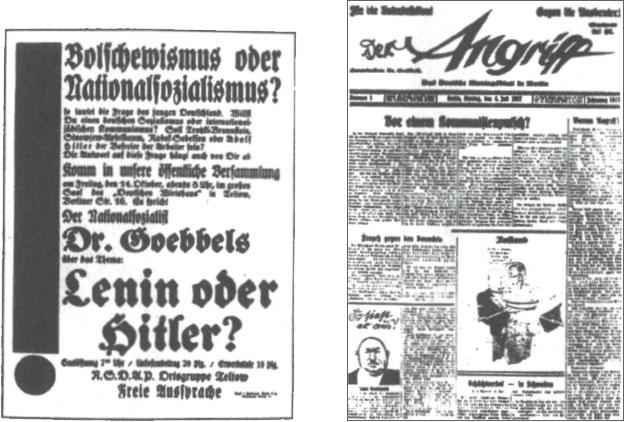

Examples of Goebbels' publicity in Berlin.

Left above and below

poster layouts, printed in red.

Right, above,

a

litfassäule

displaying a Nazi poster.

Right, below,

the front page of the fim issue of

Der Angriff

.

Otto Strasser, 1932

Gregor Strasser, 1932

Goebbels defending himself in a court oflaw, 1931.

Goebbels, 1932

He also had to master that most difficult of techniques, the art of addressing a large audience from a platform while at the same time using a microphone for the transmission of the speech over the radio. For the skilled orator direct address to an assembled audience is a matter of establishing the correct level of vocal projection that will give him complete mastery over his hearers' attention. Goebbels was, of course, thoroughly experienced in this largely instinctive technique. But to effect the right degree of projection to suit a microphone only two feet from one's face while at the same time endeavouring to reach out with his voice to the boundaries of a packed hall is a matter of highly skilled technical compromise, as Goebbels himself found.

For twenty minutes at the microphone speak to the audience in the Sportpalast. It goes better than I had thought. It is a strange experience suddenly to be faced with an inanimate microphone when one is used to addressing a living crowd, to be uplifted by the atmosphere of it, and to read the effect of one's speech in the expression on the faces of one's hearers.

47

Once the Nazis were in power the radio (then only a few years old as a public medium) was at their disposal, and new techniques of speaking had to be learned. Goebbels was soon to become an expert broadcaster.

The emphasis of the rest of Goebbels' self-portrait is on the aggressiveness and violence that was part of the Nazi character. He encourages and looks for insults in order to avenge them. “Perhaps the best way would be to have one of those scurrilous scribblers dragged out of the office by some S.A. men and publicly flogged,” he writes when he has been attacked in the

Acht-Uhr Abendblatt

.