B006OAL1QM EBOK (27 page)

Authors: Heinrich Fraenkel,Roger Manvell

Eventually the phone rang and she heard him speaking to her. His voice was calm. The first thing he said was: “I am speaking from my friend Hermann Göring's house.” Hitler had forbidden him to speak to her without a witness standing by the telephone. He called her Liduschka as he had always done, and she wept bitterly. Goebbels tried to calm her. He spoke of their duty and their need to be brave. Then he said good-bye to her, and added enigmatically and finally:

“Bleib wie du bist

; stay as you are.”

Goebbels retired alone to Lanke for a day or two to recover his self-control. Baarova was left to weep, and only Goebbels' words prevented her from carrying out her threatened suicide. Her films were removed from the screen and her contracts cancelled. She herself lay in bed, ill and hysterical. Goebbels never made any direct contact with her again; yet she stayed a while in Berlin, hoping to reach him. She did in fact see him once more before she left Berlin. Rach was driving Goebbels down the Kurfürstendamm when they saw Baarova driving her small car quite close to the Mercedes. For a while the two cars kept pace with each other, and Baarova could not prevent herself following Goebbels into the back entrance of the Ministry where she guessed he was going. The cars came to a halt. She and Goebbels looked at each other. His face betrayed no feeling, but she knew he had wanted this long, last, solemn look at her. It endured maybe barely a minute, but her memory of the moment remains undimmed by time. Then Goebbels motioned to Rach; the car slowly pulled away, and that was the end.

Hitler was, in fact, determined to keep for himself the man who was so useful to him, and he was resolved to bring Goebbels and his wife together once more. Magda at first refused to be reconciled to her husband. She still pressed for a divorce. But Hitler, who was the Fuhrer, saw to it that the reconciliation he wanted finally took place. He summoned them both to Berchtesgaden and re-made the marriage with his own hands. A celebrated photograph on the front page of the

Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung

shows the three of them together. Only Hitler is smiling. As a symbol of the reconciliation the last daughter, Heide, was conceived soon after the war had begun. She was called the

Versohnungskind

—the reconciliation child. Goebbels by then had resumed the full flood of his work and the occasional pursuit of less harmful mistresses. Von Hassell records at the end of January 1939 that “Goebbels' period of disgrace with Hitler seems now to be over”.

72

When the time came towards the end of the war at which Goebbels thought fit to burn his private papers, his aide von Oven remembers the Minister looking through a collection of old photographs. Suddenly he stopped and showed the young man a large portrait of a woman. “Now,” he said, “there's a beautiful woman.” Von Oven looked at the photograph. It was of Lida Baarova. Goebbels stared at her face for a moment, then tore the picture across. “Into the fire with it,” he said.

73

CHAPTER SIX

“These Years of Triumph”

T

HERE SEEMS

little doubt that Goebbels in spite of his venomous speeches and articles would have preferred there to be no war. He had had experience of what propaganda, backed by the parade of force and private tyranny, could effect without the dislocation of national life occasioned by the open waging of war with armies. He realised better than Hitler himself that to fight wars by means of armies meant putting the conduct of the Nazi campaign for power into the hands of professional soldiers, who would immediately be given an opportunity to attempt the frustration of Hitler's ambitions by the demands of military tactics.

However, Hitler's luck stayed with him as, one by one, he plucked the easier fruits that open warfare now permitted. The new German Empire, having already taken in Austria, Czechoslovakia and Memel (which bordered East Prussia and Lithuania) extended its range to Danzig and western Poland in 1939 and to Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and France in the spring of 1940. Later in the year Italy, which had entered the war just in time to be party to the collapse of France, invaded Greece using her bases in occupied Albania to help her. At the same time Hungary and Rumania became subservient to Germany. All these territories, whether fully occupied or not, had to be guarded and policed. They also had to be supplied with Nazi propaganda originating in the first place through Goebbels' and Ribbentrop's agents. Goebbels endeavoured to make himself aware of the state of morale in all the territories under German dominion and to devise the right variants of his basic propaganda to suit their different needs.

Hitler had become very sure of himself and the ripe, quick victories only confirmed him in his sense that his intuitive analysis of every situation went beyond the vision of the men who surrounded him. As early as 10th October 1939 he said this emphatically to his Commanding Officers in remarks such as these which occurred in a statement he made to them: “As the last factor I must in all modesty name my own person: irreplaceable … I am convinced of my powers of intellect and decision … I shall shrink from nothing and shall destroy everyone who is opposed to me …. In the last years I have experienced many examples of intuition. Even in the present development I see the prophecy.”

1

It was obligatory for Goebbels to support this self-assessment by the Führer, and whatever occasional qualms he might have had about Hitler's judgment, especially during the long intervals of the war when he was comparatively inaccessible, he never really doubted Hitler's genius. At the worst he regarded him as over-tired, misguided and ill-advised.

Hitler's desire for open war had grown as his mood had hardened, especially against Britain which he came to regard as the prime opposer of his will. He welcomed the war in the way his Staff Officers, the professional soldiers, did not. As the war progressed he approached it more and more like some avenging angel, while they saw it with the often jaundiced eyes of men concerned with practical strategy.

Even during the first two years of the war—“these years of triumph” as Goebbels called them—there were certain frustrating difficulties for a man of Hitler's intractable temperament, in particular the High Command's aversion to the invasion of Britain, Mussolini's opposition to many of Hitler's actions (especially his occupation of Rumania in October 1940) and his own basic distrust (in spite of Ribbentrop's sanguine view) of the pact with Russia, whose actions in the Baltic, when Stalin ordered the occupation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in June 1940 plainly showed that she put no trust in Germany. The Russians followed this immediately by threatening Hitler's interests in Rumania, more specially the oilfields; it was this that led subsequently to the German occupation of that country. In addition, Hitler completely failed to bring Franco into the war.

After the collapse of France, Hitler was disappointed in his hopes of a British capitulation. “I feel it to be my duty before my own con- science,” he said in a speech before the Reichstag on 19th July 1940, “to appeal once more to reason and common sense in Great Britain…. I can see no reason why this war must go on.”

2

But if Britain became the first major stumbling-block in Hitler's war (seeing that he neglected to invade and conquer her through Operation Sea-Lion), the second was undoubtedly his own overweening ambition. No sooner had he reluctantly been persuaded to postpone the invasion of England than he set the German Army the task of Operation Barbarossa—the invasion of Soviet Russia. He was also forced almost simultaneously to provide German troops to invade the Balkans because of Mussolini's surprise attack on Greece, which had not been timed in co-operation with Hitler and which he bitterly resented. Hitler found that he had to provide the stiffening necessary to keep Mussolini's armies in the field not only in Greece but also in North Africa, where the Allies achieved their first notable victory by routing Graziani's forces at Sidi Barrani in December 1940. But even while he was arranging to salvage Italian honour, he was laying the foundations for the invasion of Russia. He was also urging Japan to attack Britain in the Far East, but Japan in the end evolved her own policy and precipitated America into the war when she attacked Pearl Harbour on 7th December 1941. Once more Hitler was completely taken by surprise.

Meanwhile Hitler found that Yugoslavia, which lay in his path to Greece, dared to put up a resistance. German bombers were sent to destroy the capital, Belgrade, and in three days killed over 17,000 people. Goebbels was at his desk at six in the morning on the first day of Operation Punishment, as this avenging flight was called.

3

In the same month, April 1941, Yugoslavia capitulated and the British evacuated Greece. Mussolini's honour was for the moment salvaged. To reinforce his supremacy, Hitler sent a virtually unknown General to take command in North Africa—Erwin Rommel. British hopes of an easy victory in North Africa faded, and Hitler once more turned his attention to Eastern Europe. In a series of conferences with the High Command Hitler laid down his plans for the rapid conquest of Russia, which was to be a massive source for the supply of food for Hitler's armies. They would then be free to turn and pulverise Britain. None the less Rudolf Hess, believing he was interpreting Hitler's dearest wish, made one last sensational attempt to win a peace settlement out of Britain when he flew on his fantastic mission by Messerschmidt on 10th May 1941. Hitler, who appeared to be as amazed as Churchill at what had happened, went on with the organisation of Operation Barbarossa. The German armies crossed the Russian frontier at dawn on 22nd June. Within a few days they had driven deep into Soviet territory and within three weeks reached Smolensk, some 200 miles from Moscow.

Tactical divergencies between Hitler and the High Command then began to emerge; while the professional soldiers wanted to make for Moscow, Hitler coveted the granaries of the Ukraine. He and he alone was in a position to overrule them, and in doing so he turned what might have been a major defeat for the Russians into that phase of the struggle which was to be the turning-point of the Nazi fortunes. The Germans drove on to Kiev, and Hitler himself became confused in his selection of objectives to be reached as the autumn rains came in to prepare the ground for the snows of winter. He wanted Leningrad, he wanted Moscow (and he was only eighty miles from it in October), and he wanted the Black Sea coast and the Caucasus. The battle front stretched a thousand miles, and there were well over a million Russian prisoners to control. Göring, talking to Ciano after the November meeting with the Italian Fascists in Berlin to found the New Order for Europe, boasted that between twenty and thirty million people would starve to death in Russia during the year, and that the Russian prisoners had begun to eat each other. Hitler believed Russia to be all but defeated and forced his frozen armies to press on their campaign in appalling conditions of cold. The day before Hitler heard to his amazement of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbour, the Russians also surprised him with a massive counter-offensive designed to relieve the threat to Moscow. Nevertheless, Hitler formally declared war on the United States without any thought that the Americans might ever threaten him in Europe. Roosevelt, he declared, was the tool of the Jews.

Hitler managed to stem the Russian offensive and save his troops from a Napoleonic retreat in the depths of winter. He made himself Commander-in-Chief of the German Army; he deprived generals of their commands and, in some cases, of their rank. He let it be known that he blamed the High Command for the failure to subdue Russia. He ordered a state of no retreat, whatever the cost in lives. Inadequately clothed to resist the acid cold, his men died by tens of thousands from freezing without the need of death from the Soviet guns. At a terrible cost the Russians were held until the spring of 1942 came and Hitler was able to bring his army up to strength again, supplemented by Finnish, Rumanian, Hungarian and Italian troops which he valued only statistically . “We all fed at this moment the grandeur of the times in which we live,” he said in a public speech in March. “A world is being forged anew.”

4

He then set about reaching Stalingrad on the Volga and the Caucasian oil-fields. By September Stalingrad was becoming the turning-point of the Russian campaign, and a second winter had to be faced with an enormously elongated front. Hitler refused to see the grave dangers to which he was laying himself wide open. Goebbels was horrified by the stories his aide Rudolf Senunler told him after a period of service on the Eastern Front which culminated in Stalingrad itself:

Earlier, at the end of May, the R.A.F. made the first of its thousandbomber raids on the German war industry. Now the Germans at home as well as the Germans on the dreaded Eastern Front knew to their bitter cost the price of Hitler's ambition.

Such is the broad picture of the first three years of the war; the hundred and fifty weeks that saw the maximum of victory for Hitler before his fortunes began to recede. It was a period of intense work, interest and difficulty for Goebbels, who had perpetually to keep the limelight focused on the right news at the right time and in the right place for the right audience.

The war for Goebbels, of course, was war ceaselessly waged through propaganda. The most intimate records that survive from this period are sections of Goebbels' own official typewritten diaries (beginning at 21st January 1942) and a diary of his experiences with the Reich Minister kept by Rudolf Semmler, a member of Goebbels' staff who was promoted to serve in his more intimate circle at the end of 1940. Frau Semmler held her husband's diary after the war, and selections from it have been published. Goebbels' massive typescripts (some 7,000 sheets in all, singed and smoke-scented) narrowly escaped burning by Russian soldiers in the courtyard of the Propaganda Ministry; they were involuntarily saved by a junk-dealer in search of salvage. The task of editing a generous selection of them for publication was undertaken by Louis P. Lochner during 1947-48.

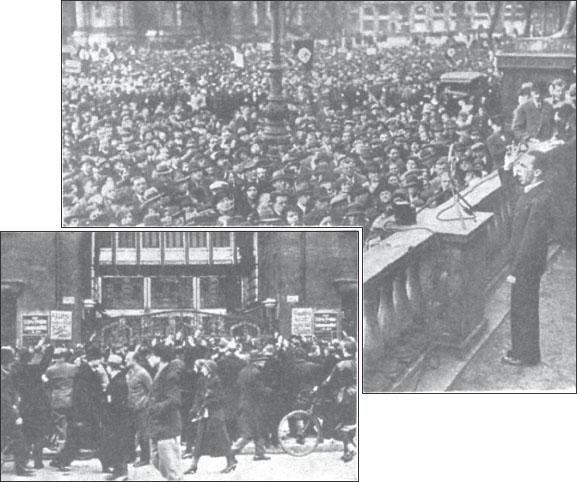

The Nazi leaders pose after Hitler's appointment as Chancellor, 30 January 1933. In the centre, left to right: Goebbels, Hitler, Roehm, Goering; Himmler and Hess, extreme right.

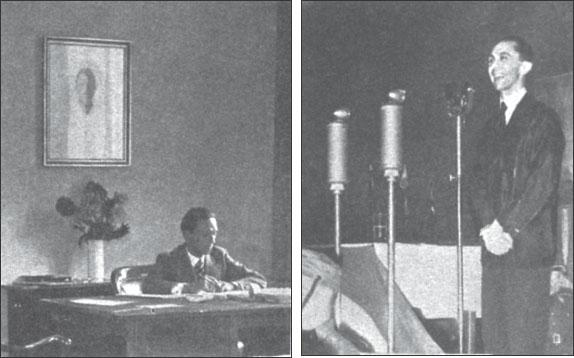

Goebbels at his desk in the Ministry

(left)

; and,

right,

on the rostrum of the Tennishallen, 1933.