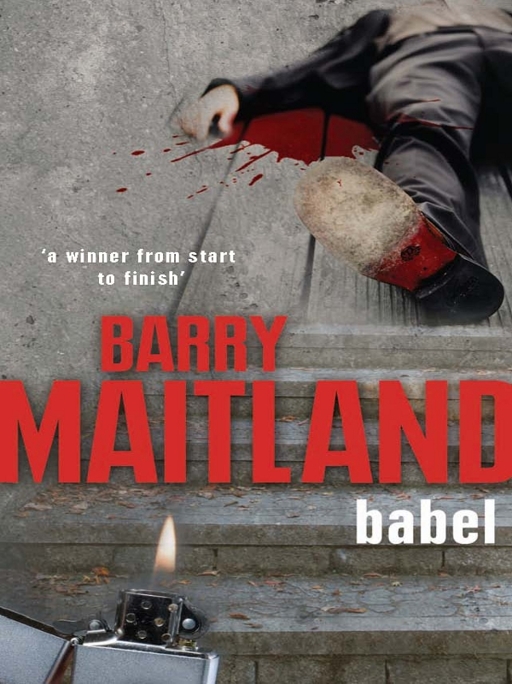

Babel

Praise for Babel

‘. . . as perfect a whodunit as you could possibly wish for. Sublime.’ —

Crime Time

‘Maitland gets better and better, and Brock and Kolla are an impressive team who deserve to become household names.’ —

Publishing News

‘Babel

is thoughtful, erudite, humane—and highly entertaining. What more could a serious crime buff want?’ —

Sydney Morning Herald

‘. . . an instant and deserved winner from start to finish. There is no doubt about it, if you are a serious lover of crime fiction, ensure Maitland’s Brock and Kolla series takes pride of place in your collection.’

—

Weekend Australian

‘Maitland is a consummate plotter, steadily complicating an already complex narrative while artfully managing the relationships of his characters.’ —

The Age

‘Maitland has always been a notable spinner of mysteries, but his latest case continues to extend his range, depth, and mastery into Ruth Rendell territory.’

—

Kirkus Reviews

‘Wow. This guy is good.’ —

Houston Chronicle

‘Maitland’s puzzle becomes more complex by the zigzag, but its rapids are a pleasure to navigate. The reading is easy, the pace deliberate, violence minimal, sexual encounters are elided, the large multiethnic cast is engaging and even the least amiable characters reveal redeeming features.’ —

Los Angeles Times Book Review

Also by Barry Maitland

The Marx Sisters

The Malcontenta

All My Enemies

The Chalon Heads

Silvermeadow

The Verge Practice

No Trace

Spider Trap

BARRY

MAITLAND

babel

This edition published in 2008

First published in Australia in 2002

Copyright © Barry Maitland 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10% of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

| Australia | |

| Phone: | (61 2) 8425 0100 |

| Fax: | (61 2) 9906 2218 |

| Email: | [email protected] |

| Web: | www.allenandunwin.com |

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Maitland, Barry.

Babel.

ISBN 978 1 74175 535 0

A823.3

Set in 10.5/12 Adobe Garamond by Midland Typesetters, Australia Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Jim

Acknowledgements

This book was written before the terrible events of 11 September 2001, at a time when the story of Islam in Britain was less widely discussed than today. I am indebted to a number of people whose knowledge and insights helped me with that aspect of the book, as well as with the workings of the Metropolitan Police. In particular I should like to thank Clare Murphy, Shiblee Jamal, Kay Suters, Rollo Clery-Fox, Ashton Nugent Cleary Fox, Scott Farrow, Anna Farrow, Akbar S. Ahmed, Philip Lewis, Fred Halliday and, as always, Margaret Maitland.

And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech . . .

And the Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which

the children of men builded.

And the Lord said, Behold, the people is one, and they have all

one language; and this they begin to do: and now nothing will

be restrained from them, which they have imagined to do.

Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that

they may not understand one another’s speech.

So the Lord scattered them abroad from thence upon the face of

all the earth: and they left off to build the city.

Therefore is the name of it called Babel.

Genesis, Chapter 11

Contents

I

entered the camp on the Saturday morning with the French medical team. The situation was overwhelming, devastating. Survivors were still being discovered beneath the ruins of demolished shelters, and all of the effort was going into finding them. That and putting out the fires whose oily smoke hung heavy in the air, blotting out the sun. The dead could wait. They lay everywhere, abandoned to the flies, sickeningly mutilated, dismembered, burned, hacked and shot. Nurses and paramedics accustomed to treating war victims were traumatised. They broke down in tears or stumbled from scene to scene in a state of shock. Some heroic figures with stronger nerves took charge of the situation and organised work groups and allocated tasks. I joined a stretcher party ferrying those survivors that we could find out to the gates of the camp where a queue of improvised ambulances waited, but each time we returned my feelings of fear and revulsion increased. Finally I felt so contaminated by the horror that I became convinced that the insanity of what had been done there would infect my own reason. Deep in the camp I abandoned the team and attempted to find my way out. But I became lost and disoriented in the winding alleyways, and staggered from one part of hell to another. I came to a place where limbs, torsos, heads lay scattered in my path and panic engulfed me. Then I heard a voice, the voice of a child, though I could see no one. It seemed to be reciting something rhythmical, a nursery rhyme perhaps, or a prayer. I was transfixed.

Its source lay in the dark shadow beneath a black awning collapsed close to the ground. I knelt before it and looked into a small space and made out the figure of a woman, her head cradled in the arms of a small boy. I discovered that my feelings of terror and disgust had left me. I crawled into the space. The woman was quite dead, her stomach bearing terrible wounds, but her son, a child of eight years as I later established, was unhurt. I sat with him for some time, and told him that his mother was past help. He had fallen silent when I appeared, and I never heard him utter another sound. I promised to take care of him and finally persuaded him to leave his mother’s body and come with me. He was very thin and seemed to weigh almost nothing as I lifted him into my arms. I carried him out of the camp, holding his face close against my cheek so that he would not see the sights that we passed.

D

etective Sergeant Kathy Kolla felt a great weariness overwhelm her. She didn’t want to appear obstructive, but the room was warm and she hadn’t slept for so long.

‘It’s all in my report. You’ve read that? I really can’t add . . .’

‘I’ve read it, yes,’ the other woman said gently. ‘It’s very objective. It must have been extremely difficult to write. But it doesn’t tell me how you felt, how you feel now.’

I feel now that my body is made of lead, she thought, heavy, dumb, grey. But she said, ‘I felt mainly helpless.’

‘Was that the most terrible thing about it? That you felt helpless?’

‘Yes.’

‘Abandoned?’

‘Maybe. Towards the end.’

‘That would be the time of the rape, would it?’ Such a gentle, supportive voice.

‘He didn’t rape me.’

‘No, you said that. You said he was stopped. You’re quite sure about that?’

‘Christ, I should know.’ A little buzz of shock made Kathy sit up straight. Did they not believe her?

‘Yes, of course. So the worst thing was the feeling of helplessness.’

A silence. The woman was good at silences, Kathy thought, but she had sat through enough interviews at the side of Brock, the master of the unbearable silence, to know how they worked.

Eventually the woman broke it herself. ‘And feeling abandoned?’ she prompted. ‘Did you feel let down by your colleagues for not getting you out of there?’

‘No, I’d got myself into the situation. It was my mistake.’

‘All the same . . . You didn’t feel the least bit angry? With DCI Brock, perhaps?’

‘No.’

‘You’ve been in a number of difficult situations before, as a member of his team, haven’t you?’

‘Yes.’

‘But this one was different?’

‘Yes.’

‘Because . . .?’

‘Because . . . this time I really believed I was going to die.’

The woman seemed about to pursue this, then studied Kathy for a moment and appeared to change her mind. ‘Yes, it must have been awful,’ she murmured. ‘We might come back to that later, if you like. Tell me a little more about yourself, will you? You’ve lost both your parents, I understand. Do you have any other close family?’

‘I have an uncle and aunt in Sheffield, and a cousin and her family in Canada. They’re the closest.’

‘No brothers or sisters?’

‘No.’

‘Close friends?’

‘The people I work with.’

‘I mean, anyone special, a partner?’

‘Not at the moment.’ Kathy was aware that she was making the woman work, but she couldn’t help herself.

‘Recently?’

Kathy didn’t answer, staring at the carpet, a neutral soft grey. But this time the woman wasn’t going to give up. Finally Kathy said. ‘I was living with a man in the latter part of last year. We split up just before Christmas.’

The woman gave her a careful look. ‘Immediately before this happened?’

Kathy nodded.

‘Do you want to talk about that?’

‘No. It’s got nothing to do with it.’

‘You’re quite sure?’

Another little buzz of shock. She hadn’t even considered that possibility, blanking it out. ‘Quite sure.’

The woman could barely disguise her disappointment. ‘Well . . . Is he a policeman?’

‘Yes.’

Another extended silence.

‘What about girlfriends? Do you have a close friend you can confide in?’

‘I have a few friends, but no one particularly close.’

‘Outside of the force?’

‘Not really.’

The woman checked her watch. ‘Our hour is up, Kathy,’ she said, with a little frown of concern. ‘The next time we meet I’d like to explore a bit more thoroughly your feelings in that room, if you’re up to it. Between now and then, you might like to think about how those feelings relate to the rest of your life.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘I mean, can we isolate what happened in that room and deal with it on its own, or do we need to consider other aspects of your life in coming to terms with it?’

She caught the look on Kathy’s face and quickly added with a smile, ‘Don’t worry, it’s just a thought.’

A bitter January east wind was blowing in the street outside. Kathy stood a moment on the front steps breathing it in as if it could scour away the sense of numbness that had weighed her down during the session. The street was crowded with people hurrying towards the evening trains and buses that would carry them back to their homes in the suburbs, and she fell in with them, glad to walk before facing the next trial.

Half an hour later she stood outside the door of the pub where the team was meeting to celebrate Bren Gurney’s promotion to detective inspector. Just a quiet do, Dot the secretary had said, a couple of drinks after work. Almost three weeks had passed since the events of Christmas Eve and this was the first time Kathy had seen them all together. She wanted to let them see that it was behind her now, that she was ready to rejoin the living.

She spotted them as soon as she stepped inside, a small group clustered at one end of the bar, indistinguishable from the other knots of office workers catching a quick one before heading home. Bren was at their centre, the largest figure of the group, eyes alight, eyebrows climbing up his prematurely balding brow as he recounted some story. It was said of him that he had refused to go for this promotion, long overdue, because he had been told that it would mean his transfer to another unit. But persistence was Bren’s strength, and now his patience had been rewarded. Kathy was glad for him. After Brock he was the rock of the group, the steady, soft-spoken west countryman you’d want at your side when things started going badly wrong.

Brock was sitting on a bar stool, slightly apart, contemplating his pint, and looked up as she moved forward through the crowd, as if he could sense her approach. For a moment before he spotted her she felt a tremor of panic and almost ducked and ran, but then it passed and he was beaming, waving her over, saying something to the others who turned and gave a cheer. She grinned and stuck up her chin, accepted the hugs and handshakes, and gave her congratulations to Bren.