Babel No More (33 page)

Authors: Michael Erard

As Cox well knew, there’s a persistent myth that hyperpolyglots are able to maintain very high skills in each and every one

of their languages. When this can be proven false, then they’re considered to be discredited. You can graph this by putting on the

y

axis a global measure of language skills and proficiencies, and on the

x

axis the number of languages, which looks like this:

Figure 3. Imagined distribution of a hyperpolyglot’s language abilities.

Yet hyperpolyglots are not unique in this—the same myth applies to bilinguals. The reality, as bilingual researcher François Grosjean notes, is that “some bilinguals are dominant in one language, others do not know how to read and write one of their languages, others have only passive knowledge of a language and, finally,

a very small minority have equal and perfect fluency in their languages.”

As I had discovered, the actual curve of skills and proficiencies over number of languages looks (roughly) more like this:

Figure 4. Actual distribution of hyperpolyglots’ language abilities.

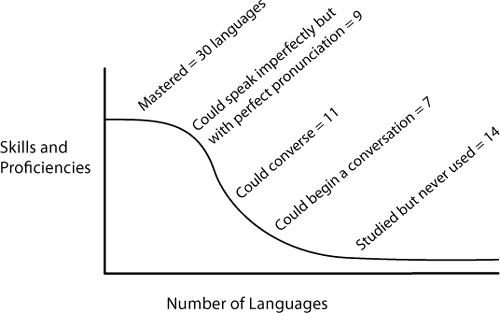

Where you can find data for specific people, you can plug them into the curve. Let’s use Charles Russell’s careful accounting to generate one for Mezzofanti. We know that he didn’t speak or read all of his languages to equal degree—one group he had to a very high degree (though the figure of thirty might be exaggerated), and

his “surge” languages to some middling degree, along with the “bits of language” on the tail end.

Figure 5. Distribution of Mezzofanti’s language abilities.

You can produce a similar curve by plugging in modern criteria and data from contemporary hyperpolyglots. For instance, Air Force officer Edgar Donovan scored 3 (out of 5) in listening and reading in Spanish, Italian, French, and Brazilian Portuguese, and 2 (out of 5) in European Portuguese. In his other languages, he has negligible

proficiency, and he received a number of zeros (meaning that he knows practically nothing of the language) in Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish, and Serbo-Croatian.

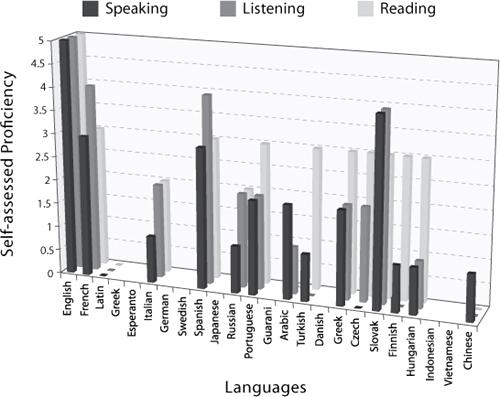

A more extensive picture came from Graham Cansdale, the European Commission translator I’d described to Loraine Obler. He possessed a cluster of Geschwind-Galaburda traits (gay, spatially limited, verbally gifted). After meeting Graham in his

office, I stayed in touch with him. Later he agreed to rate his abilities in all of his languages using surveys of speaking, listening, and reading that were adapted by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. The surveys are based on a scale first developed by the US State Department’s

Foreign Service Institute in the 1950s (the test became mandatory for all foreign service

officers in 1958) and modified over the following decades by the Interagency Language Roundtable (ILR), an informal group in the federal government that shares information on language teaching and testing.

As is the case with the Defense Language Proficiency Test, the ACTFL scale makes the educated native speaker the pinnacle of achievement. Still, the scale suited my purposes well, especially

since everyone knows its shortcomings. Using a full version of a proficiency test would have been expensive and time-consuming. We also know there’s good correlation between the skills that someone reports and their actual skill level.

*

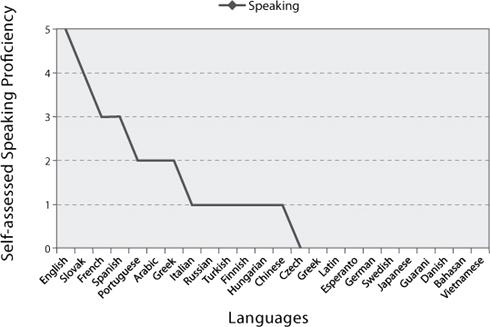

I interviewed Graham about his language learning history, which provides the basis for the

x

axis of

Figure 6

; the

y

axis is the ratings of the ILR scale. Graham

then filled out the self-assessments. The standards grade on a scale from 0 to 5. In speaking, for instance, a 0 means no proficiency, 0+ refers to an ability to use rehearsed utterances, while 5 is a “functionally native proficiency.”

Figure 6

is Graham’s total language system, which is a patchwork of proficiency. Here’s a native English speaker, raised monolingually, who now lives in predominantly

Francophone Brussels with a native Slovakian speaker (which explains his strong oral skills on all three) and who uses a range of languages for his work. There are higher scores in reading than in speaking because he’s a translator; even so, he said he’s reached a “critical mass” in some of the languages, so that his abilities degrade more slowly. Not only does practice matter, but having

consolidated certain languages, such as Spanish, by living in a place also helps. (One benefit of his job is substantial opportunities for travel and professional development.)

Figure 7

graphs his total speaking proficiency.

Of particular interest is that he claims no perfect score in any language but English, and in one-third to one-half of the languages he has studied, he has no skills to

report in speaking, reading, or listening.

Figure 6. Distribution of Graham Cansdale’s self-reported proficiencies in speaking, listening, and reading, arranged by language biography (2010).

This curve appears to map onto Graham’s biography, such that his later learned languages appear lower on the curve. Alternatively, it might reflect how much practice he gets in which languages. Or it might map both. The fact that there appear to

be three clusters of abilities—very high ones, a set of middling ones, and a long tail of very low ones—reflects the three levels of retained knowledge that linguists Kees de Bot and Saskia Stoessel laid out in an exploration of how people lose and relearn languages. At the highest level is knowledge that remains active. At the next level are items that can be recognized passively. At the third is

knowledge that was thought lost but is still there—things that had been “saved.” Saved languages are important to hyperpolyglots—over and over, people mentioned their “surge” languages proudly. But such knowledge isn’t quantified in the modern language testing world. Aptitude can’t account for it, either.

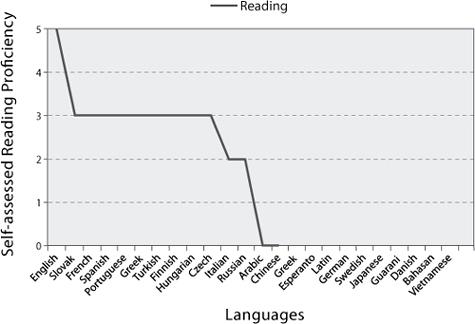

Earlier I suggested that reading and translating activities require less mental effort than

speaking. Indeed, in

Figure 8

is how Graham assessed his reading proficiency; note that the line doesn’t drop off as sharply as the speaking curve. He’s able to read more languages than he can speak.

Figure 7. Distribution of Graham Cansdale’s self-reported proficiencies in speaking, arranged by score (2010).

Figure 8. Distribution of Graham Cansdale’s self-reported proficiencies in reading, arranged by score (2010).

I also asked experts how many languages a person could control—how many they could switch back and forth between with no confusion. They said that there was no theoretical limit to the number of languages one could learn. Time, not cognition, seemed to be the limiting factor. “There’s

really no limit to the human capacity for language except for

things like having enough time to get enough exposure to the language,” said Suzanne Flynn, a psycholinguist at MIT who studies bilingualism and trilingualism. “It gets easier the more languages you know.” Harvard University psycholinguist Steven Pinker agreed. Asked if there is any theoretical reason someone couldn’t learn dozens of

languages, he replied: “No theoretical reason I can think of, except eventually interference—similar kinds of knowledge can interfere with one another.”

But there are

real

limits—ask hyperpolyglots themselves. Out of respect for Erik Gunnemark, I’ll count only the contemporary superlearners. Gunnemark, in a letter to Alexander, wrote that “if you read or hear that a certain person ‘can speak’

(or ‘speaks’) a large number of languages (for instance twenty or more) you should always be a little skeptical.” Gunnemark insisted that only thirteen languages be attributed to him, those he spoke “fluently” or “fairly well.” He never counted the fifteen languages he spoke at a “mini” level. (Amorey Gethin, who collaborated with Gunnemark on

The Art and Science of Learning Languages,

told me

in a phone call that “I don’t think [Erik] could speak very many languages very well—but he could read them. He could read quite a few languages.”)

A clearer limit came from my survey. Out of 167 respondents, only twenty-eight said they knew ten or more languages; only seven knew fifteen or more; and the highest number claimed was twenty-six. One thing to note is that my standard was very broad—people

didn’t have to speak the language (they could also write it), and the definition of “knowing” was up to them. I don’t know if they were counting all the languages they had ever encountered or all the ones they claimed to have readily accessible. Either way, one consequence is that if you thought Ziad Fazah and Gregg Cox had exaggerated, you’d really think so now. The map of what’s possible,

even at its extremes, doesn’t seem to extend to fifty-nine (for Fazah) or sixty-four (for Cox) languages simultaneously. Among other things, this would seem to invalidate Cox’s

Guinness

record. (Yet I’m not inclined to diss

Guinness

record keeping altogether, as you’ll see.)