Back to the Front (20 page)

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

Ghosts everywhere. Even the living were only ghosts in the making. You learned to ration your commitment to them. This moment

in this tent already had the quality of

remembered

experience. Or perhaps he was simply getting old. But then, after all, in trench time he

was

old. A generation lasted six months, less than that on the Somme, barely twelve weeks. He was this boy's great-grandfather.

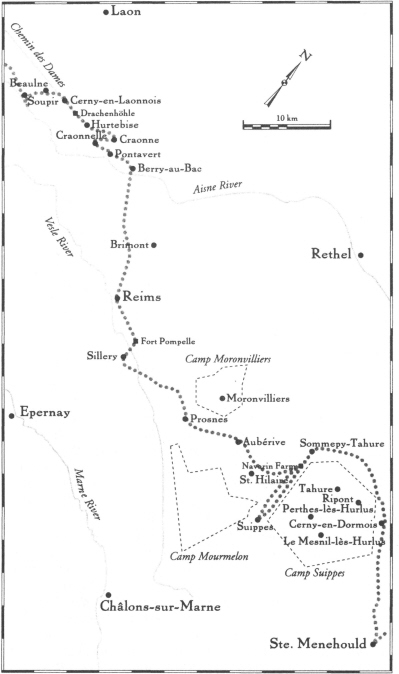

I. Cerny-en-Laonnois to Craonne to Berry-au-Bac

T

HE DRY, HOT

Assumption holiday under a leaden August sun begins in Picardy and finishes in Champagne. There is an end to

the summer in sight, as the blue line of the Vosges grows closer with every step I take. I shall walk out of the last of the

scarred Picard woods today and into the great chalky Champenois dust bowl that stretches out from the sacred city of Reims

to the dark hills of the Argonne. The agony of the Front continued on beyond Champagne, into Lorraine and Alsace, but perhaps

nowhere was the sting of incompetence as sharp as right here, along the Chemin des Dames.

The attack launched here in the spring of 1917 showed French military planners to be a band of blinkered dilettantes, like

so many rubes hopelessly outplayed and outpositioned in a game of skill. For

dames

is also the French word for checkers, and on this crimson landscape the German generals knew every move of their opponents

in advance and countered devastatingly. Tens of thousands of ordinary soldiers were killed, swept off the checkerboard thanks

to the impossible tasks set for them. The sheer magnitude of the rout at the Chemin des Dames called for the enforcement of

willed amnesia. The French army—any army, in fact—is a natural enemy of truth. Alliances shift, but the opposition between

the logic of military obedience and that of informed criticism will always remain. Arguably, covering up its blunders and

cruelties is what the French army has done best in the twentieth century.

It waited until 1995, for example, before one of its official spokesmen begrudgingly allowed that Alfred Dreyfus had been

wronged one hundred years previously. Similarly, its behavior during the war of Algerian independence in the 1950s and 1960s,

during which thousands were tortured and killed by French officers, remains a taboo subject in French military and political

circles. The smothering of the Chemin des Dames debacle and its aftermath followed the same implacable need for mendacity.

In a well-known instance of the long hand of military censorship reaching across time, Stanley Kubrick's

Paths of Glory

—a film made in 1957—was successfully kept off French movie screens until well into the 1970s. Its depiction of the unfair

courts-martial of poilus for insubordination in a futile Great War offensive was considered too biased for the impressionable

minds of French moviegoers.

The graduates of French military academies after World War I would learn precisely the wrong lessons from the Chemin des Dames

fiasco. They poured all their efforts during the interwar period into building a useless fortification, the Maginot Line,

as a means of thwarting any other Schlieffen-like German attack on France. The decision to build the Line—it failed miserably

in 1940 — rivals the plan of attack along the Chemin des Dames as an illustration of awe-inspiring incompetence. As I write

these words in the 1990s, the current generation of bemedaled French strategists is exploding nuclear bombs under a Pacific

atoll in anticipation, perhaps, of some future aquatic threat. History will judge whether these fellows are any cleverer than

their predecessors.

Such judgment goes by the name of hindsight, a backward-looking, second-guessing perspective that I have often used in recounting

the events at the Front. Professional historians find hindsight unjust, even distasteful; I believe it to be a necessary weapon

to fight against the apologists of mayhem. Scholars quite rightly point out the exaggerations of popular rumor and the paranoid

imaginings of the mistreated—no, hundreds of men were not shot as a result of the Chemin des Dames mutinies, as was once commonly

believed. But as these overblown bubbles of oral transmission get punctured, sometimes the emphasis gets shifted. The hunt

for inaccuracy becomes paramount, and in redressing a minor libel the original enormity gets lost. No, Haig did not bungle

everything, completely, all the time, but—lest we forget—he did send hundreds of thousands unnecessarily to their deaths on

two occasions. The men who routinely referred to him as "the Butcher" are all dead and gone now, yet his statue still stands

in London's Whitehall. Haig and Joffre and Falkenhayn and their ilk died not on some hopeless, hellish battlefield but of

old age, in their beds, and their memory, while fading, is still honored in some quarters. We have forgotten how heinous a

lesson about the military mind they inadvertently taught the world. The twentieth century's opening event, the murder of millions

through incompetence, has become unacknowledged, and the perpetrators unpunished in our vision of the past. A little less

intellectual charity toward them is in order, even if that means using the disreputable narrative tool of hindsight. The reluctance

to put one's life in the hands of the military, an ancestral reflex made universal by the Great War, should never be allowed

to weaken.

T

HE CHEMIN DES

Dames cries out for hindsight. It is hard to imagine a stupider place to order an attack. Seeing is disbelieving.

In the valley below Passchendaele, I had to picture the mud, reconstruct the horror from accounts I was reading; to the uninformed

eye, the notorious spot looks like an unprepossessing village in an unremarkable landscape, but not much else. The Somme,

too, looked innocuous, or, at least, like a place where the attacker in a war was not automatically doomed to failure. It

was command error on a colossal scale rather than the nature of the terrain that had led to the mass British suicides in 1916.

Not so the Chemin des Dames. The landscape is such that no casual hiker with a knowledge of the past can fail to pity the

poor poilus ordered to assault the German lines here. When I leave Soupir to head northward, the road starts to ascend and

will not stop its ascent for a couple of miles. North of the River Aisne between Soissons and Reims the land resembles a tall

escarpment. The incline is steep in parts. On either side of my route outcroppings of the plateau summit, some three hundred

feet above the floor of the Aisne valley, jut out from the body of the incline. Imagine an oak leaf a hundred yards thick—its

lateral lobes are these jutting cliffs, from which machine-gunners had a field day mowing down the men slogging up the gentler

slopes to the flat land at the top. To attack here was insane.

My walk continues in the building heat. The floors of the reforested parts of the slopes show the customary egg-carton craziness

of Great War carnage; the plowed farmer's fields, the usual collection of dud shells and rusted bullets. Near a village called

Beaulne, I quickly pass some old bones piled up against a fencepost. This time the toponymic coincidence does not charm. I

am eager to finish the ascent.

The top is the location of the

chemin

of the Chemin des Dames, a road used by the daughters of Louis XV whenever they visited a noblewoman of the district. These

grandes dames

enjoyed the road—the midrib of our oak leaf—because it provided such dominating views to both north and south. The distant

spires of Laon and Reims could be glimpsed on very fine days. What provided agreeable scenery from a jolting eighteenth-century

carriage also made an admirable firing range for twentieth-century gunners looking downhill. To worsen matters for the French

attacker, geology favored the defenders too. The rock of the plateau is porous—indeed, the great cathedrals of the region

had been built from the stone quarried here—and the land was already a maze of tunnels and subterranean chambers long before

the engineers of the German army dug shelters deep into the ground. The moles who built the redoubtable blockhouse into the

gulley wall of Nampcel would use all the advantages of malleable stone here. At the easternmost point of the Chemin des Dames,

where the upland is called the California Plateau, a series of underground tunnels was so extensive that it could comfortably

hold 8,000 men. The German soldiers, never at a loss for Sturm und Drang modifiers, named the feature

die Drachenhöhle,

the Dragon Hole.

The French plan of attack was simple. Thousands of troops, less than six months after escaping from the slaughter of Verdun,

were to proceed uphill, between machine-gun-infested cliffs, in full view of an impregnable enemy, with no attempt to use

the element of surprise. How could the French command have done this to its soldiers? Good question. What's even more puzzling

is how the civilian authors of a major French two-volume compendium,

La première guerre mondiale,

could write as late as 1968: "Strategically, the attack sector was judiciously chosen because, as long as the breakthrough

occurred in the first twenty-four or forty-eight hours, the entire center of the German line would collapse. Unfortunately

for the French, no ground was ever better suited to the defensive." Love of the dialectic—or at least its first two contradictory

statements—must have afflicted the writers. If the terrain was so formidable, how could the sector have been "judiciously"

chosen? The slope up toward the Chemin des Dames is an infantryman's graveyard. And when did great French breakthroughs

ever

occur in the First World War? Passages such as these litter books on the war, as if military historians never visited battlefields

or realized that the men in the fanciest uniforms frequently have a lot of unfurnished rooms upstairs. To understand the Chemin

des Dames, it is not necessary to find lame excuses; it is far better to understand 1917.

O

R, RATHER, THE

result of 1916. Between them, the strategists of the French, British, and German general staffs had managed

to kill more than one million men in nine months—and the Front had not budged. Small wonder that political leaders began to

question the abilities of their generals. The near-loss of Verdun had led to Joffre's being promoted beyond the reach of the

levers of command. The man responsible for the most horrendous casualties in French history—hundreds of thousands of his countrymen

killed in incessant, repetitive attacks in Lorraine during the debacle of 1914—was raised to the rank of field marshal. Ever

the dullard in tactics, he initially did not realize that this meant he would lose effective control of the armies.

Perhaps Joffre thought he would be treated as gently as the British treated their commander. Douglas Haig—the man who made

July 1, 1916, the worst day in all of British martial history—was also elevated to the heights of field marshaldom, but he

was not relieved of command. His protector and patron, King George V, wanted to show some overt support for his friend and

reward him for standing up to the assaults of the new prime minister, David Lloyd George. The king rightly saw that Haig was

in danger of deserved demotion. Lloyd George, just as rightly, viewed the new field marshal as a plodding old soldier with

too little imagination and talent to be left in charge of so many British lives. The Somme had sickened Lloyd George—he wanted

to see anyone but Haig conduct the battles of 1917. The prime minister, unable to fire the well-connected bumbler, would henceforth

look to circumvent his military commander.

Unfortunately for the poilus of 1917, Lloyd George and other politicians fell under the spell of the French general Robert

Georges Nivelle, a heretofore obscure officer who had scored a few high-profile victories in the closing days of the Verdun

battles. Much of the ground he won back had already been evacuated by the Germans, but the symbolic purpose of regaining lost

territory did not escape the notice of a French press desperate for good news after the horrible losses of the year. Nivelle,

perhaps the most canny manipulator of opinion of the entire war, was soon considered by almost everyone as a man with a plan,

a bold new tactician who would somehow outsmart the stubborn realities of trench warfare. What had actually happened in his

Verdun successes—a short, intense artillery barrage on a very small front, followed by an advance over ground that was in

the process of being surrendered—got lost in the enthusiasm for Nivelle's messianistic military message: I can win the war.

I have the secret. Everything is under control.

He was saying it in English, too. Nivelle, whose mother came from Britain, was an urbane man who could knock back port with

the best of his cross-Channel colleagues and speak English fluently and persuasively. Nivelle's cozy parleys with Lloyd George

clinched his appointment as military supremo. He was believed in both languages, because people in power hoped that the searingly

murderous mistakes of the past could somehow be halted. This new general exuded self-assurance; he had, after all, won battles

in the world's most awful battlefield. Nivelle was charming, cultivated, and convincing. The French populace, and, more important,

the French army, took him at his word and dared to hope that the end of the war was just around the corner. Not since 1914

had there been such optimism afoot. To be fair to Nivelle, he believed his own hype.

Once made de facto commander-in-chief of the Allied effort, Nivelle worked only minor modifications to Joffre's plan for 1917,

but they were crucial nonetheless. The British would attack near Arras, the French at the Chemin des Dames. This way, the

new commander hoped, the Noyon Salient, that weak, quiet sector of the line, would be cruelly pinched, and the Germans would

have to waste their reserves in shoring up their defenses.