Back to the Front (9 page)

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

I reach Messines. Its unsightly church stands out like a black eye in the blameless blue sky. The original, ruined church

was the subject of sketches by Corporal Adolf Hitler, who spent much of the war in the trenches on this ridge. I pause in

a cafe to make notes and put my feet up on a wicker chair. A chain-smoking twelve-year-old wordlessly serves me a coffee,

holds out his hand, then pockets my coins, all without once meeting my

eyes.

This must be the Paris of Flanders.

The land drops off suddenly south of Messines into a succession of golden fields. The scene seems anonymously pastoral, but

this stretch of land is anything but nameless. In the valley lies a still-active western front of Europe, this one far more

enduring than that dug by the ghosts of 1914. Here the tiny River Douve separates the Flemish province of West-Vlaanderen

(West Flanders) from an enclave of the Walloon province of Hainaut. On one side of the stream is Germanic turf; on the other,

Latin. This linguistic front runs through Belgium and Luxembourg, separates Alsace from Lorraine, then meanders through the

Swiss and Italian Alps before finally confronting another line, that of the Slavs, in the Balkans. In western Europe, the

Latin-Germanic divide was lastingly established when Charlemagne's heirs sliced up the pie between Salic Goths and Ostrogoths

in A.D. 843. The treaty giving rise to this age-old western front was signed—where else? — in Verdun.

As I cross the small bridge spanning the Douve, I'm stepping on both

een brug

and

un pont.

Ahead are

un arbre

and

une ferme\

behind,

een

boom

and

een boerderij.

Birds wheel back and forth, becoming

oiseaux

or

vogels

in turn; clouds overhead change from Flemish

wolken

to French

nuages.

Not that much else changes, even if I do expect to see more gold chains and fewer spiky haircuts as a result of crossing the

cultural divide. I am reminded of going from Ontario to Quebec over the Ottawa River, except that here in Flanders it is the

French-speaking side that holds out the promise of greater familiarity. Although Flemish may be English's first cousin (or

cousin germain,

as French so aptly puts it), I feel more at home with my north Latin in-laws, having spent a dutiful Trudeau-led boyhood in

quest of French-English bilingualism. The next time I'll cross this line, at the only other point of intersection between

the two fronts, is eight weeks away in the Vosges Mountains, where the French spoken on the western slopes gives way to the

Alsatian on the eastern.

Almost immediately on leaving Belgium's linguistic divide of the Douve, I enter the trees of Ploegsteert Wood and encounter

the monuments that mark the southern extremity of the Ypres Salient. Two large stone lions sit before a rotunda on which the

memorial makers, once again seeking absolution through accountancy, have etched another long list of young men whose bodies

were never found. The proud felines, I assume, were placed there to cloak the grisly proceedings with imperial grandeur. The

trick may have worked once, in the glory days when the sun never set on either gin or tonic, but it doesn't any longer. Now

the reference to a defunct empire, here in a Belgian grove, seems pathetic. The lions' time had passed even when they were

being sculpted—it was precisely because of the Great War that the dominions of the Empire distanced themselves from Britain.

There remained, of course, links between crown and former colonies, some of which survived as tenacious throwbacks well past

the mid-century mark. I need only think of my second-grade teacher teaching us Boer War songs in the shadow of the Rocky Mountains.

An elderly New Zealander couple befriends me in the neighboring Hyde Park Corner Cemetery. Our acquaintance doesn't start

off well, as conversation quickly bogs down in Commonwealth cross-purposes. The man, fearful that a Yank like myself will

mistake them for Australians, insists on telling me several times that he and his wife are Kiwis. Fortunately, she interrupts

him.

"Look at that," she says, pointing down at what seems a standard headstone. "It's disgraceful."

I read: "A Soldier of the Great War Known Unto God," the euphemism coined by Rudyard Kipling to describe an unidentifiable

body. It'sa phrase etched on countless headstones along the Western Front. I'dalways thought it rather elegant."

And over there," she continues, gesturing to another row of headstones.

Her husband walks a few paces, squats down, and starts to weed the grass. I begin to understand."They've really let the side

down. In France, they've done a lovely job, but here . . ." At the thought of imperfect gardening her voice trails off in

disgust.

This is the couple's third trip to the old battlefields. Each time, they have tried to keep the groundskeepers of the Commonwealth

War Graves Commission "on their toes." It's a hobby.

Messines, they go on to tell me, was the scene of a heroic New Zealand action in 1917, and is thus a well-known name in the

antipodes. Ploesteert Wood, in which we stand, is famous for two things. It once held the house where Churchill did his brief

tour of duty in 1915, and it still holds a gigantic unexploded mine from the 1917 offensive. It used to hold two, but one

exploded in 1955, apparently detonated by a stray thunderbolt striking a tree. The remaining mine has yet to go off, and no

one has volunteered to go digging for it.

The New Zealanders climb back in their car and drive off north to give the gardeners of the Salient graveyards a hard time.

I strike out south for France, setting a fast pace for these last few level miles. Once out of the woods I head through the

village of Ploegsteert, where a woman with a sad smile hands me a pamphlet protesting a proposed hazardous waste depot in

the area. First a time bomb, now a toxic dump—this is not a blessed corner of creation.

Half an hour later, border bars and discount shops begin to thicken along the roadside. Le Bizet, once a dormitory town for

Belgian laborers who toiled in the brickworks across the way in France, now lives off a few French bargain hunters and day-trippers.

At the border crossing, my status as disheveled pedestrian is immediately noticed and judged suspect. I'm waved over into

a French customs office where, of the five young men in uniform, only one is not playing with a lighter, reading the paper,

or listening intently to AM radio.

My arrival in the shed creates a stir. The backpack is emptied, and the search for illegal drugs almost instantly abandoned

once the nature of my belongings is seen. My silver hip flask earns admiring wolf whistles. The linguist of the five correctly

guesses it contains Irish whiskey, given the "O" in my last name. This inspires two others to crouch before me for a mock

scrum—France and Ireland play every year in the Five Nations rugby tournament—that is interrupted by a shout

of"Putain!"

One of the boys has found on my maps the obscure border post where he is to be transferred. Just the other day he was trying

to tell the others about it, and they didn't know where it was.

His explanations are cut short. A dignified man enters the shed. He has swept-back gray hair and is wearing an understated

blue suit. He greets each officer individually, then turns to me, unsure of what to do next. He glances down at my boxer shorts

on the table, which seem to help him come to a decision. He shakes my hand, utters a perfunctory

"bonjour,"

then turns on his heel and walks out.

Seeing my puzzled face, a customs officer explains:

“Maire adjoint.

Socialiste."

O

N THE WAY

into the deputy mayor's town, Armentieres, I see a directional road sign pointing to nearby Bailleul. During the

Race to the Sea in 1914, the townspeople of Bailleul fled in terror, and the retreating German army let the inmates of an

insane asylum run free in the deserted streets. This incident, which inspired film director Philippe de Broca'sclassic pacifist

farce,

King of Hearts,

is not difficult to dredge up from memory after spending time in the Bizet customs post. Inmates still run a few asylums in

French Flanders.

I walk into the large town square of Armentieres, a paved expanse used as a parking lot. Somewhere a reconstructed belfry

chimes out the time. A few cafés give out onto the square, the clings and clangs of their pinball machines adding to the late-afternoon

carillon. The city, once famous as a party town for British troops, was leveled in the fighting of 1918 and hastily reconstructed

afterward. A song, " Mademoiselle from Armentiéres, " became an anthem for soldiers in this sector, its countless verses —

raunchy or polite, depending on the audience—always concluding with the chorus, " Hinky-dinky (or " Inky pinky") parlay-voo.

" There are worse ways to end a visit to Flanders:

“Mademoiselle from Armentieres, parlay-voo?

Mademoiselle from Armentieres, parlay-voo?

Your eggs and frites, they give us the squits.

Hinky-dinky parlay-voo.

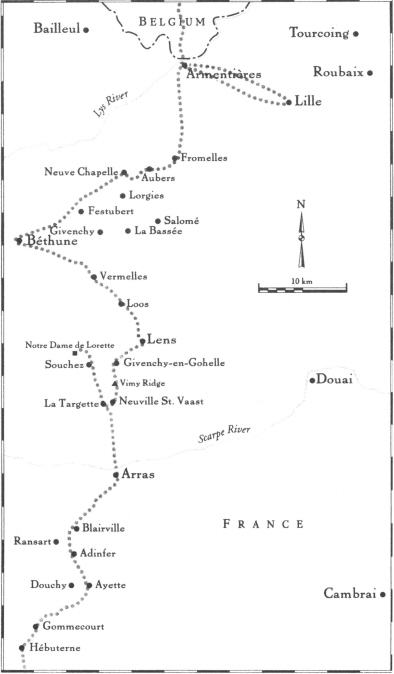

••••• author's route

i. Lille to Aubers to Neuve Chapelle

T

HE RAIN FALLS.

Armentieres becomes a puddle in search of the hole in my shoe. I take a commuter train to the capital of French

Flanders, Lille, and put off for a day my journey south to the slag heaps of Artois. I bring a book with me,

Pride and Prejudice,

and read it in a restaurant. Elizabeth tells Darcy to take a hike just as it's time for me to go back to the Front and do

the same. I forget to look at Lille.

Ten years later Lille will be an aspiring Europolis, a showcase of shiny technology parks and shopping centres. The high-speed

train that goes under the Channel will stop at a glitzy, glassy station in the middle of town. Lille as a satellite of Brussels,

a suburb of London, a city in eastern Kent—all notions that would cause its most famous son, Charles de Gaulle, to turn over

in his tank. Expressways and express rail lines stream west of Lille toward England. The tiny cemeteries and memorials in

the fields near Armentieres, St. Omer, Bailleul, and Hazebrouck flash past

the

windows of the TGV trains like places not really seen. The very speed of passage mocks the unmoving behemoth that once lay

over the countryside. No-man's-land is crossed in seconds, as coffee is poured and another Eurobun buttered. The Chunnel shall

one day fog the British memory of war, for much of their national myth-making is tied up with going abroad to fight, with

sailing out to meet the foe. What meaning "fair stood the wind for France" or "there's some corner of a foreign field / That

is for ever England," when making the once fateful trip takes less time than crossing London on the Underground? The notion

of France will have been rendered domestic. Wogs no longer start at Calais, Wogs 'R' Us.

Somewhere in this land rich in anachronistic borders and fronts is yet another invisible line, the shared boundary of Flanders

and Artois. The current

departements

are Nord and Pas de Calais, but the long-standing regional names serve the purposes of this account better, for they conjure

up a history, a sense of the past. Roughly speaking, Artois is the upland separating the forests of Picardy and the basin

of Ile-de-France from the great northern European plain beginning in Flanders and continuing through the Netherlands, Germany,

and Poland. Yet the boundary that matters most, I tell myself as I study my maps in puzzlement, is the line of the Front.

To be more precise: the Front as it was in 1916, the year of utter stalemate, the Front I have set out to see. In 1917 and

1918 the lines moved considerably in northern France, making any retrospective hike down no-man's-land an event for a zigzagger

of Olympian stamina. With that in mind, a few miles south of Armentieres I declare myself to be in Artois.

In fact, I have just entered a different type of buffer zone: suburbia. A landscape of bungalows lies ahead. On the road surface

are speed bumps or, as French highway slang has it, "sleeping policemen." Somehow it's more satisfying to drive over them

that way. I assume that the residents of this subdivision work in Lille, the big city, and not Armentieres, the small town,

because the dogs I encounter here are quivering little neurotics, more fashion accessories than faithful companions. Thus

the preemptive tactic I've been using to confuse charging farm dogs—I bark first—fails miserably. These inbred suburbanites

obey only their nerves. One toy-sized beast barrels out of a front gate, unimpressed by my bared incisors, and lets off a

volley of yaps that drills deep into my inner ear. The two of us stand our ground in the narrow street, snarling theatrically

at each other. I finally let loose a howl and lunge forward. The beast skitters back through the gate, its barking all the

more furious for having given way to a bigger opponent. I move on, but not before glimpsing the curtains of the bungalow's

front room fall back into place. So I'm not good with dogs, lady.

The tract housing thins and the cemeteries start cropping up again. The land is riddled with roads and tracks laid out in

a grid pattern. There are far more people living here than in the countryside of Belgian Flanders. Farmhouses have been gentrified,

rowhouses decorated, and a few garden sheds left in artful disarray. I pass several abandoned brickworks, testament to a once

thriving industry. Catholicism's taste for the big gesture also appears. The crossroads around here are just that—roads with

crosses. At several junctions, there are man-sized crucifixes on which are nailed extravagantly suffering Christs, like butterflies

under glass. They look down at me as I sweat in the morning sun.

At a hamlet called Fromelles I pass a roadside Calvary that's not on my map. Kitty-corner from Christ there's a country cafe,

which I enter to ask directions. Behind the counter a woman in a blue paisley smock watches bugs affix themselves to a long

strip of flypaper. She glances up as I close the door behind me.

"Are you looking for a job? Because there aren't any to be found around here."

I think briefly about the

King of Hearts,

then shake my head. I tell her I'm looking for the road to Aubers.

This doesn't cut it as a ploy to change the subject. She tells me that unemployment has hit the area hard. Her daughter can't

find a job and "might even have to go to Lille." I point out that Lille is only a dozen miles away. The cafe lady is not interested

in geography. She tells me that unemployment is a scourge for young people today.

A man of about seventy comes in the door, smiling and ready to engage in debate. I like him instantly. He's wearing a gray

tweed cap, a blue and white zip-up sweater, and navy-blue polyester bell-bottoms. He greets the cafe owner deferentially,

as if he's conferring a prize on her, then fires a question at me that I can't quite understand. The French language streams

out of his mouth, in a singsong accent I've never heard before. This is the legacy of the

chti

(pronounced "shtee"), the patois of northern France. The old man is what's called a

chti'mi:

He speaks French the way a Welsh auctioneer would speak English. On the third time around I understand what he's saying.

"Vous etes oisif msieu?"

He's asking me if I'm idle. I look at him, then at the cafe lady, suspecting that they're some sort of non sequitur tag team.

When I admit to loafing, I learn that today is a wonderful day for the idle—and that the old man has a wonderfully idle life.

His wife in the city, his children gone, no one around the house, he can go and relax in the fields with his newspaper. Sometimes

he sits up and reads it, sometimes he just lies down and covers his face with it. You can never be too careful with the sun.

Especially at this time of the year. If you're not careful, you can get sunstroke. That would be unfortunate, for then you

couldn't read the paper, could you?

He stops for a breath.

The three of us spend an enjoyable Socratic moment together, the old man posing questions then running away with the answers.

When it's time for me to resume hiking, my two companions, satisfied that I'm idle but not looking for a job, direct me to

a cow track leading to the village of Aubers. I promise, nodding my way out the door, to stay in the shade as much as I can,

to avoid sunstroke, to enjoy idleness, to take a bus if I get tired, to profit from my youth.

A

UBERS, WHICH CAN

be made out in the distance, sits on a slight rise in this transitional area between Flanders and Artois.

In May of 1915, the British tried to storm the rise, to prove to their French allies that they were willing to take casualties.

In that respect the attack was a success. They were mowed down by machine guns, and about 12,000 men were lost. At Fromelles,

in 1916, it was the Australians' turn. Advancing without reinforcements, they stormed the German trenches, then were cut off,

surrounded, and massacred. In some Australian battalions, more than 80 percent of the men were killed.

The pastures between Fromelles and Aubers are dotted with the crumbling remains of pillboxes. Beside one of them, as if just

placed there, is a bouquet of fresh flowers. There is no card.

The flowers in the field hint at the profusion of blossoms in the handsome red village of Aubers. Despite the old man's opinion,

his is not a village of the indolent. The houses, neatly rebuilt from the heaps of broken brick that were left after the armies

had moved off in 1918, look well maintained and welcoming. The Front, a strip of Europe where nothing is old, where most things

were reconstructed on the cheap in the 1920s and 1930s, has thus far been a succession of sad villages and soulless towns.

Aubers seems determined to shake off the past, or at least cover it up with flowers.

At a fork in the road below Aubers, signs indicate the way to "Salome" and "Lorgies." Both destinations sound like a good

time, but my route lies elsewhere, down a gentle grade to the southwest, toward the village of Neuve Chapelle, another name

in the annals of folly. The British made a successful surprise attack here in 1915. It was a surprise despite themselves—they

did not have enough shells to launch a long preliminary bombardment and thereby give away their intentions. In one morning,

they took the town and even managed to break through into the countryside beyond it. The 1,400 Germans holding the lines at

Neuve Chapelle could not withstand the onslaught. They were outnumbered thirty-five to one.

Then the British stopped, as a result of the indescribable confusion reigning in the command structure. Reinforcements were

sent up far too late, officers in adjacent units did not answer to the same commanders, and communication became a tangle

of orders and counterorders. For most of the afternoon of March 10, 1915, there was a gaping hole in the German lines, but

it was not exploited. Tens of thousands of men sat on the ground smoking, waiting to be told to go forward. The generals,

as can only be expected of Great War stories, ordered the attacks renewed long after the Germans had had the time to shore

up their defenses. Slaughter ensued. The Germans counterattacked and regained much of the yardage they had lost.

This did not play well in Britain, where expectations had been raised by reports of early success. The war, rejoiced the editorialists,

was almost won. A scapegoat was needed for the reversal of fortune. Since the generals, John French and Douglas Haig, could

not very well blame themselves and didn't dare blame the thousands they had just sent to their deaths, it was thought best

to lay the whole thing at the doorstep of the British worker. There had not been enough artillery shells, army spokesmen declared,

because the British worker was a shirker who spent all his time getting drunk. That was why Neuve Chapelle had been a disaster.

The civilian government dutifully ordered British pubs to lock up in the afternoons, a law that remained on the books until

1989, when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher decided that the threat to the war effort was over.

O

UTSIDE NEUVE CHAPELLE,

in a quiet semi-suburban street near the ruins of a lethal fortification known as the Quadrilateral,

the locals appear to have launched a lawn gnome war. Dwarfs, trolls, and

schtroumpfs

—smurfs, in English—stand in competitive quantities before a row of recently built houses that coincides with the farthest

advance of the British line. Aside from the gnomes, the only statuary of note is in the village itself. At a bend in the road

is yet another Christ in agony, a replacement for a more famous fellow sufferer. The Portuguese, who held this part of the

Front in 1918, were so surprised by a German attack during the spring of that year that they fled Neuve Chapelle without the

legless crucifixion scene they had been lugging around with them for good luck. Happily, this so-called "Christ of the Trenches"

was found after the war and restored to them. The villagers had to settle for a new Christ, which they erected at an unmissable

spot on the highway leading out of town to Armentieres.

That Christ is not, however, at Neuve Chapelle's most striking crossroads. Just west of the village, on the way to the town

of Bethune, is an unprepossessing old inn called the Auberge de la Bombe. The name is just a coincidence, the owner tells

me in the parking lot. I'm not convinced but say nothing—our immediate surroundings are too distracting. Near la Bombe is

a Portuguese military graveyard, a reminder of the 1918 surprise German attack. Beside it, dominating the junction, stands

a large memorial with gray granite tigers and lotus blossoms rising up from the dusty fields. Delicate stone latticework and

Sanskrit lettering run down the side of twin pavilions. This is the principal Indian memorial of the Western Front. Troops

from India were in the vanguard of the Neuve Chapelle fiasco of 1915, betrayed by the incompetence of their colonial overseers.

I try to get a closer look at the structure. Wherever there are large stone felines, I've noticed, there is usually a British

embarrassment. The louder the roar, the emptier the tribute. The gate is locked.

I get a lift into Bethune from the innkeeper of the Bombe, a man in his forties. Signs for cemeteries in Festubert and Givenchy,

outposts of no-man's-land, flash by on the roadside. I ask him what he thinks of Indians and Portuguese coming to die in his

grandfather's backyard.

He whistles and says, "Unbelievable. This place is still unbelievable."

2. Béthune to Loos to Lens

Béthune, explains the driver giving me a lift in from the strange crossroads at Neuve Chapelle, is a

ville bourgeoise.

Lens, the other big town in the area, is a

villepopulaire.

Which means that the one houses the owners, and the other, the workers. Which also means that you can't have fun in Bethune.

I tell him that during the First World War there was a famous brothel in Bethune, called the Red Lantern.

He looks at me and says that if it's still there, he hasn't found it.

I'm let off in the central square, an improbable collection of skinny shop facades and bunkerlike bank fronts. A medieval

belfry, reconstructed after the Great War, stretches skyward over a midsummer crowd sucking down colorful drinks. The tall

tower is the town's pride, a symbol of the city's freedom from feudal obligations. In the Middle Ages, the burghers of Flanders

and Artois erected belfries to cock a snook in stone at churchmen and nobles.