Ball of Fire (47 page)

“The show was built on an entrancing pseudo-effect of the real: that the very ordinary couple portrayed was played by a real couple, one of whom was extremely famous, successful, and rich. Lucille Ball, a real star, became a goofy housewife named Lucy Ricardo, but nobody was fooled. Didn’t we smile when we saw the heart-shaped logo at the end: Desilu Productions?

“That was the fun of it—the confusion and mixture of televised fantasy and voyeuristically apprehended reality. A dose of fantasy. And the insinuation that we might be watching something real. Which has turned out, fifty years later, to be television’s perennial, still winning formula.”

Not all voices were so upbeat. During a seminar in Las Vegas, a member of the audience asked Jerry Lewis which female comics he admired. “I don’t like any female comedians,” Lewis said. Moderator and fellow comedian Martin Short brought up the name of Lucille Ball: “You must have loved

her.

” “No,” insisted Lewis, “a woman doing comedy doesn’t offend me, but sets me back a bit. I, as a viewer, have trouble with it. I think of her as a producing machine that brings babies into the world.”

A backhanded eulogy came from underground-film director John Waters, who claimed that Lucy Ricardo was a profound influence on

Polyester

and

Hairspray.

Waters remembered

I Love Lucy

as the show that changed his life: “At last, a female impersonator who dyed her hair orange, wore obviously false eyelashes and scary red lipstick at home, married a man of another race, got pregnant on television, hung out with her blue-collar neighbors, and ran away to pal around with Rock Hudson. As an eight-year-old voyeur, looking ahead to my teenage years was a lot easier because of

Lucy.

I knew you could break the rules.”

Darker notes were sounded in

Talk

magazine, when Rex Reed compiled a set of interviews with some of Lucy’s colleagues and relations. Her longtime friend Sheila MacRae remembered an occasion at the Arnazes. “We were all having dinner with William Holden and his wife and watching a movie, and Lucy said, ‘Take it off. It’s all about people having sex.’ She started to cry and there was dead silence. It was very embarrassing. There were only six people in the room. Desi said, ‘For Christ’s sake, Lucy!’ She said, ‘I’m going to leave you.’ He said, ‘So go ahead. What do I care?’ And he moved into the guesthouse.”

Actress Carole Cook recalled: “I went to see her on the set of that last show that she did and she was in a tirade. I said, ‘Gosh, Lucy, you’re working again.’ And she said, ‘They just don’t like women over fifty.’ I said, ‘You’ve been over fifty a long time, you know? If it’s your first bad review, that’s not such a bad deal.’

“I always thought it was sad that a woman like that—who could have done charity work, gone to the theater, traveled, read, held classes—spent her dumb days playing backgammon.”

Actress Polly Bergen described her Roxbury Drive neighbor in very specific terms. Lucy’s “outer persona as a performer was this cute, bubbly, zany character. But in her personal and social life she was a very tough broad.”

Paula Stewart blamed Gary Morton for much of Lucy’s downhill slide toward the end. “She was taking all these different medications and she was very sick. The high blood pressure was the killer. She was depressed and she was having a hard time with Gary. They were not getting along. But she still liked the margaritas with salt, and she’d sneak sardine sandwiches. You know, anything with salt. And Gary would say, ‘Oh, let her have the salt.’ ” Several years later, during one of Lucy’s hospital stays, “she needed a nurse to watch over her. Gary let the nurse go. He said it was too expensive. I said, ‘What? She’s one of the richest women around.’And not only that, but her insurance had to be paying for everything. What could that nurse have cost?”

Lucy’s publicist, Thomas Watson, said: “She never raised herself to grow old gracefully. She used to tell me, ‘I am not Helen Hayes.’ She should have retired.” When the last series failed, “she didn’t know what to do. Gary never said, ‘Show business is my life.’ He always said, ‘Show business is my

wife.

’ ”

Lucie Arnaz weighed the pros and cons of her mother’s life and career. “On the positive side, she had tenacity, an amazing ability to keep going until she got it right. Bravery. She was the first to do things that women didn’t do. She was gifted, she had genius, like Chaplin. Artistry of the top rank. On the negative side, she was tactless with some people. Brusque. She wasn’t able to really be open, close, intimate with a lot of people. That was a negative—for her and for what we lost as a family.”

Further details were added in London, where Lucie starred in a West End version of

The Witches of Eastwick.

Understandably, the

Daily Mail

interview was never reprinted in the States. By the time her mother had assumed the presidency of Desilu, said Lucie, Desi was gone and Lucy worked “from dawn to dusk. She didn’t need the money, she had everything she wanted, from clothes to jewels to cars. Yet only work mattered. She could be very cold and although she told me she loved me all the time, I didn’t feel loved. When children don’t feel they deserve love they start feeling unworthy of love . . . and I felt like that most of the time.” Lucie went on: “I never wanted to behave to my own three children the way my mother did with us, never being there to talk to us, to get our breakfast, to bathe us, to read us stories at night. We had people to look after us and my grandmother was there sometimes. But I couldn’t wait to leave home and I did at 18. I got married to the first man I went out with.” She assured Lucy, “I can make it work,” but she found that she couldn’t. “I’d made a terrible mistake and within a year it broke up. I’d made a terrible mistake.” The three children she had with Laurence Luckinbill, plus the two from his previous marriage, caused some difficulties. “At first I used to be quite sharp with my kids because I had nothing to follow, nothing to learn from.” Much as she admired her mother’s talent, Lucie concluded, “I just wish she’d been there to give us the love that we so desperately needed.”

But the sorrier aspects of Lucille Ball were more than counterbalanced by the perceptions of adoring fans and colleagues, who would hear no disparagement of the loved one. In an article on images that make men cry, the

New York Times

cited Douglas McGrath, the director of the movies

Emma

and

Nicholas Nickleby.

“I’ll be in bed at night with my wife,” he confided to a reporter, “and a rerun of

I Love Lucy

starts, and just as the heart is closing around the title, the tears well up in my eyes.” According to the paper, McGrath thought it was “because of the contrast between the triumph of love of the fictional Desi and Lucy, and the fact that they broke up in real life.” Added the

Times,

“Now that’s a sensitive guy!” Likenesses—rather inflexible likenesses, it must be said—went on display at Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum in New York and at the Hollywood and Movieland Museums in California. Lucy’s star was burnished on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Statues, whose intent was more laudable than their execution, could be found in Jamestown; at the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame Plaza in North Hollywood, where Lucy had worked; and in Palm Springs, where she had vacationed. In Dallas, her words were inscribed in the Women’s Museum: “You really have to love yourself to get anything done in this world.” In 2001 she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York, where the first Women’s Rights convention was held in 1848.

In New York City, summer school students in the English as a Second Language program at Bushwick High School were presented with an unusual assignment. They were shown the job-switching episode of

I Love Lucy,

in which Ricky and Fred turn househusbands and Lucy and Ethel take jobs in the chocolate factory. They were then to write papers on what they had viewed. The purpose, said the Board of Education, was twofold: “to immerse students in the language, and to introduce them to cultural institutions.” Elsewhere, Dr. Seth Shostak, an astronomer at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute, groped for a proper way to explain the reach of light and sound in space. “The nearest star is about four light-years away,” he said, “and there are on the order of several thousand stars within the fifty-light-year range. So the earliest episodes of

I Love Lucy

are washing over a new star system at the rate of about one system a day.”

All measuring devices agreed: the status of Lucille Ball was permanent, on Earth and beyond it. That being the case, entrepreneurs, indiscriminate fans, hypercritical scholars, feminists, and revisionists all moved in. The Internet, growing exponentially in the 1990s, offered more than one hundred Lucille Ball Web sites, and the number has grown since then. Some are electronic stores, offering every conceivable sort of souvenir connected with Lucy’s glory days. The home page of Cathy’s Closet displays a quote from Lucie Arnaz: “The only closet with more ‘authentic’ Lucy items than Cathy’s was my mother’s!” No one is likely to challenge that statement; Cathy’s Closet offers some fifty categories of merchandise arranged alphabetically, including Ceramic Boxes, Figurines, Games, Mouse Pads, Snow Globes, Tote Bags, and Watches. Everything Lucy, a similar site, but bearing no Arnaz endorsement, sells such exotica as “I Love Lucy” Chocolate Factory salt and pepper shakers, a large “I Love Lucy” cookie jar in the shape of a car seen on the series, and an “I Love Lucy” bear. The items are not cheap; the cookie jar, for example, sells for $149.99. Collectors can buy dolls that range back to the 1950s and go up to the present, including a “Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz Bobblehead Set” issued by Classic Collecticritters; “Celebrity Barbie” dolls by Mattel, featuring Barbie and Ken dressed as the Arnazes; and the “Lucille Ball Vinyl Portrait Doll” from the Franklin Mint, priced around $200.

The most dedicated fans, however, are less interested in accumulation than in making points about their favorite. Oxygen Media, whose television channel and Web site target a female audience, regards Lucy as an avatar of women’s rights: “Generally, what she wanted was to play a less passive role, to be more actor than acted upon. She wanted attention and what’s wrong with that? We all want it; Lucy was just very up-front and focused about getting it. Not one to repress her insecurities, Lucy tackled them head-on, and since her fears were our fears, we rejoiced in her flagrant disregard for propriety in her quest for inclusion.”

Michael Karol, author of that compound of insight, fact, and trivia Lucy A to Z, conducts the serious, if worshipful, site

www.geocities.com/Sitcomboy/

. On it he examines the influence of

I Love Lucy

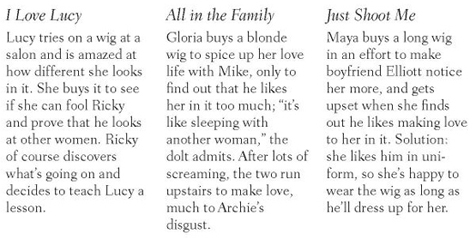

on situation comedies that followed in its slipstream:

Sitcomboy rushes on: “If you’re a dedicated channel surfer, unique delights await you. Within the space of a few hours just recently, I saw ‘Lucy’ make an appearance on the Simpsons (as Lucille MacGillicuddy Ricardo, I believe): she turns up to help Lisa Simpson, who’s having a problem managing Homer and Bart while Marge is in the hospital. And then, a bit later, I was passing through VH-1 when I noticed a familiar drummer: Desi Arnaz, Jr. Intrigued, I watched as Dino, Desi & Billy (the rock trio that had some minor success in the 1960s) played a forgettable love song, then went to be congratulated by Ed Sullivan (the show itself was a syndicated clip fest of rock moments from his Sunday night show). Ready to keep surfing, I stopped as Sullivan introduced one of the trio’s mothers from the audience—none other than Lucy herself.”

The feminist site Lucille Ball Is a Cool Woman! stresses the influence of Lucille Ball on female entertainers—and on American women in general: “One of the most important things that Lucy showed us was that women could be funny and attractive all at once—a groundbreaking concept for the day. This was particularly admirable given that Lucy was beautiful enough to be a conventional film star, and, in fact had become a Hollywood movie sensation as ‘Queen of the B-Movies.’ But she shrugged off the persona of a cool beauty, instead reveling in the chance to get a laugh. She was never afraid to look foolish, silly, or even ugly for the sake of a good gag and her public loved her for it. By proving this formula, she paved the way for generations of funny women to come. Think of Carol Burnett, Roseanne, Gilda Radner, and Candice Bergen—they all owe at least a part of their success to the amazing Lucy.”

Floating above these fans’ notes is the Higher Criticism—inquiries about, and analyses of, Lucille Ball as comedian, artist, and executive. Molly Haskell, one of the most prominent and discerning critics of popular culture, had her say in a piece entitled “50 Years and Millions of Reruns Later, Why Does America Still Love Lucy?” To Haskell, the answer lay in Ball’s subversive approach. “Although the Lucy persona would disavow any connection with feminism,” the author asserts, “in her own foot-in-mouth way, she cuts a wide swath through male supremacy, saying anything that comes into her head and taking down sacred cows and chauvinist bulls along the way. Trying to say ‘thank you’ to Ricky’s pompous Cuban uncle, and garbling her Spanish, she calls him a fat pig before accidentally (?) shredding his foot-long, hand-rolled cigar—no mean symbol of Lucy’s assault on puffed-up male potency.”