Ballet Shoes for Anna (3 page)

Read Ballet Shoes for Anna Online

Authors: Noel Streatfeild

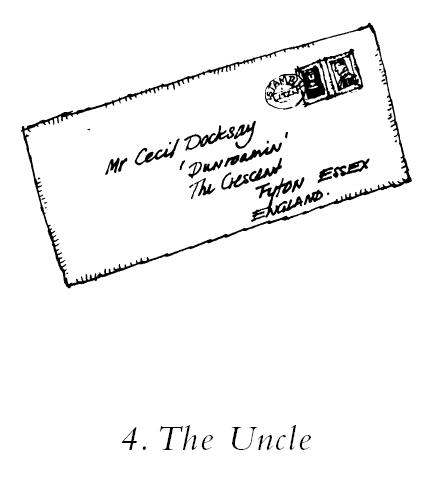

Cecil Docksay lived with his wife Mabel in Essex. His house was in a place called Fyton. Much of Essex is very pretty but Fyton was not because it was mostly badly designed new houses which crowded round the church, a village green and three thatched cottages. But Cecil Docksay thought his house perfect because, as he was always saying, it was so labour-saving and therefore easy to run.

It was a neat house outside and in. Upstairs it had three bedrooms: one the big main room which they shared, two small spare rooms in which everything was always in dust-sheets because they never had a visitor to stay. There was, too, a magnificent bathroom.

Downstairs there was a big room which they called the lounge. This was full of green velvet furniture and had a white wallpaper with a design on it of trellis work up which

climbed ivy. On the walls there were no pictures but a trail of ceramic geese in full flight.

The lounge looked on to the garden, which was even more labour-saving than the house for everything in it was made of plastic. The garden was covered in concrete pretending to be crazy paving. In the middle of the concrete there was a small pool by which sat two scarlet gnomes apparently fishing, only there were no fish in the pool, not even a tadpole in the spring. Instead of flower beds there were metal containers and in these lived plastic plants which were changed to suit the season. In the spring they were full of daffodils and hyacinths. Then those were sponged and put away and out came rose trees and other summer flowers. When the autumn came it was goodbye to the summer flowers and a splendid show of plastic chrysanthemums took their place. Everybody else living in Fyton grew real flowers and, though their gardens were small, they worked very hard to make them look and smell beautiful.

“So foolish,” Cecil Docksay would say to Mabel as he watched their neighbours struggling with greenfly or deadheading their real chrysanthemums. “What I say is why make work?”

Mabel did not answer for she liked real flowers but to say so would only mean an argument.

At the front of the house was the dining room, in which the table and chairs were made of something which looked like wood but was unmarkable, because it was heat-resisting, dirt-resisting – in fact there was nothing it did not resist

including being nice to look at.

The kitchen was Mabel’s pride. It was quite a large room and had been bought exactly as it stood at an exhibition called “The Home Beautiful”. It was the most labour-saving kitchen ever invented. The house was called Dunroamin.

The day the letter arrived was wet and stormy. Cecil and Mabel Docksay were having breakfast, Cecil looking with pride at the way their plastic rose tree stood stiff and resistant to the rain and wind, while their neighbours’ roses, which had been beautiful, took on that sad stuck-together look which roses have on wet days.

Mabel Docksay had always been a shy person. Her mother had been good-looking and popular with a large circle of friends. She would have liked to have a pretty little girl of whom she could have been proud. So it was annoying for her that she had a child who tried to make herself smaller than she was so that she would not be noticed. If her father had been about he would have understood and sympathized with Mabel for he was shy himself, but he was out at work all day so had never seen much of his daughter.

Mabel had worked hard at school but she was more a plodder than clever, so she was not able to fulfil her dream which was to be sent to a university, which would mean living away from home. Instead she had settled for a job in the local bank. “Well, I suppose at least it’s a safe job,” her mother had said to her friends, “and she needs a safe job, poor darling, for she’s so shy and I’m afraid rather dull, so she will never marry.” Of course Mabel knew this was what her

mother believed so she thought herself the luckiest girl in the world when the assistant manager at the bank, Cecil Docksay, asked her to marry him. She was so grateful to be asked, which meant getting away from home and living in a house of her own, that she mistook gratitude for love. Her father did worry about the marriage for he thought Cecil Docksay a terribly dull man.

“You’re very young, Mabel,” he had said. “Don’t rush into anything you might regret.”

Mabel with shining eyes had replied:

“I’m rushing to do what I want to do.”

Just about the time Cecil Docksay, by then manager, retired from the bank his father and mother died so, since Christopher was forgotten, he inherited all the money there was and was able to buy Dunroamin. Mabel thought Dunroamin was a pleasant house and knew she should be happy to live in it and grateful to dear Cecil for buying it, but somehow she didn’t feel any of these things – only rather depressed.

Who wants two silly gnomes? she thought resentfully and secretly looked enviously out of her windows at other people’s children. Oh, if only she and Cecil had had a child!

On the wet and stormy morning when the postman knocked on the door Mabel jumped up to get the post, for Cecil was not the sort of man whom anyone would ask to open a front door.

There was only the one letter – a long white envelope with Turkish stamps. Cecil opened the envelope carefully

with a knife for it was a good envelope which could be used again, and he was nothing if not careful. He noticed it had been sent from a hotel in Istanbul. Then he looked at the end of the letter to see who had signed it but he couldn’t read the signature. But the hotel secretary who had typed the letter had typed at the bottom “Sir William Hoogle”. Cecil knew that name for having been a bank manager he prided himself on knowing who was who.

All the papers had carried the news that Christopher Docksay had been killed in the earthquake. To Cecil, Christopher’s name was not one to be mentioned, for having run away to Paris with his father’s possessions he was a thief so best forgotten. In Fyton it had not yet crossed anyone’s mind that the odd Mr and Mrs Docksay who lived in Dunroamin and planted plastic flowers instead of real ones could possibly be related to anyone famous, especially not to a famous artist.

On the radio the newscaster had said that of recent years Christopher’s pictures had fetched a lot of money, which had made Mabel ask:

“Are you his heir, dear?”

“I suppose so,” Cecil had agreed. “No doubt someone will communicate in time.” Now, as he started to read his letter, he said to Mabel: “This is from Turkey, no doubt about Christopher’s estate. Wonderful how quick they were finding my address.”

But as Cecil read the letter a great change came over him. He made so many grunts and growls that Mabel trembled.

That was how she saw his colour change from yellow (he was a pasty man) to red and finally to purple. When he came to the last word he thumped his fist on the table so hard that if anything could have marked it that would have.

“I won’t have it! Prying busybody! Why should he take it upon himself to find my address? How does he dare dictate to me what I should do or not do?”

“Who, dear?” Mabel asked.

Cecil could hardly speak he was so angry.

“Sir William Hoogle. It seems Christopher was married to some Polish woman and they had three children.”

Mabel did not know who Sir William Hoogle was, or what Cecil was so angry about, so she said, trying not to sound as thrilled as she felt:

“Three children!”

Cecil could have hit Mabel for repeating every word he said. He’d give her something to repeat.

“Listen!” he roared. “This is the last paragraph of the letter: ‘I plan to deliver the children to you at the end of the week. I will cable the time of our arrival.’ ”

The day after Sir William arrived at Camp A the children were better. The terrible cold which followed the earthquake was gone, so they sat in the sun outside the hospital tent to eat their breakfast and that’s where Sir William found them. They looked, he thought, a pathetic lot of little ragamuffins, for you can’t be thrown about by an earthquake and finish up either clean or tidy.

“You lot want some new clothes,” he said. “We must go shopping.”

Anna looked surprised at such ignorance.

“There are not shops here and the clothes at the relief places are not yet for children.”

“Some will be coming,” Gussie explained. “The nurse told us.”

“I don’t think we’ll wait for that,” said Sir William. “Let’s go to Istanbul. Good shops there.”

The children stared at him. Of course they had heard of Istanbul but they had never been there. Christopher had never gone to a town unless he had to. Towns were tiresome about parking a caravan. Francesco, used to travelling at a speed chosen by Togo, suggested:

“Isn’t Istanbul rather a long way away?”

Sir William took a cigar from his pocket and lit it.

“A long way away from where?” he asked.

Well, that was a question. It brought all three children slap up against the things they did not want to think about. Where now was home? Everybody was gone – Christopher, Olga, Jardek, Babka and Togo, the little house and the caravan. When they went away from where they were now they had no place at all to come back to.

Francesco gave a shiver as if it was cold again. Gussie looked as if he might be going to be sick, which he had been off and on since the earthquake, and two tears trickled down Anna’s cheeks.

“I’m sorry,” she choked, “but you shouldn’t have asked

that.”

“Nonsense!” retorted Sir William. “You can’t live in a hospital tent for ever. You have been given into my charge for the time being and I don’t intend to let you out of my sight until I see you settled. Now, Francesco, you are the eldest. Tell me what you know of your family.”

Francesco wanted to be helpful but all the family he knew were dead. However, Sir William was aware of that so he must mean farther away relations.

Then Gussie said:

“There was the father of our father.” He turned to Francesco and Anna. “He was that horrible man who would not let Christopher paint.”

Francesco remembered, for Christopher had often told the story. He looked at Sir William.

“So our father had to take things from the house to sell for the air fare to Paris where he must learn to paint.”

Sir William nodded.

“Good thing he did, for he became a very fine painter. Do you know where this grandfather of yours lived?”

All the children shook their heads. Never once had they heard a place mentioned and, never having been to England, they would not have remembered if they had. Then another piece of information came into Gussie’s memory.

“The brother of our father was already in a bank while Christopher is in a school.” He looked triumphantly at Francesco and Anna. “You remember Christopher telling us that?”

They did indeed. Riding along a yellow dusty road in Pakistan. It was not said to them but to Olga.

“This is the life, Olga. I love it. The sun to beat on your head, the smell of spices up your nose and a caravan for a home. And to think if my father had had his way I’d be shut up in a bank. I might even be on the road to becoming a bank manager. I suppose Cecil is one by now unless he’s retired.”

Recalling that scene hurt so much the children would have wished to change the subject, but they liked Sir William and he was trying to help so Francesco said to the others:

“I suppose Cecil is a bank manager now.”

Sir William was not the sort of man who missed anything anybody said.

“Who is Cecil?”

Christopher had told so many funny stories about his brother Cecil it seemed strange anybody didn’t know who he was.

“He is the brother of our father. He is The Uncle,” Gussie explained. “He is already in a bank when Christopher is at school.”

“Is he married?” Sir William asked.

The children shook their heads.

“We do not know, he was in a bank when our father is first leaving to paint in Paris,” Francesco explained. “For two years our father sends his father and mother a Christmas card.”

“With funny drawings of himself on them,” Gussie added.

“And his address,” Anna reminded them.

“But the father is still angry,” said Francesco. “He never

answered. Never at all.”

Sir William saw he had got all there was to know out of the children. He had plenty of influence and Docksay was an uncommon name. If any of the family were alive he would run them to earth.

“The army say the runway will be open tomorrow, in which case we should get a plane for Istanbul. From there I will telephone London to inquire after your relations.”

“But they don’t sound very nice,” said Gussie.

Sir William smiled comfortingly.

“If we find them you can try them out. I shan’t be far away, I’ll keep in touch.”

Francesco remembered that Sir William did not know the important thing.

“Anna has to learn to dance.”

“Real proper learning,” Gussie added. “For Jardek, our mother’s father, was a great teacher and he said Anna was special, she was going to be such a dancer as he had always prayed he would teach.”

Sir William knew very little about dancing, but he was an optimist and did not believe in imagining difficulties – time enough to worry when they cropped up.