Barracuda 945 (28 page)

Authors: Patrick Robinson

“Vice versa, it’s a similar chain. Reduce power draw-off, increase temperature of water back into the core. Reduce neutron population, reduce fission rate.

“But that doesn’t mean we all have a nervous breakdown whenever we speed up. The whole system is very largely self-regulating. Strictly hands-off. We don’t do anything; we watch. We watch like

fucking arctic eagles for anything that can go wrong…. That’s the engineering officer’s task.”

“Ben’s a very good student, right?” said Captain Vanislav, chuckling, and adding with a mock-serious expression, “Of course, I had to get him into shape at first. He’s a little impatient, sometimes little bit arrogant. You know, his daddy’s a very big man. But he’s very good. He was Russian, I give him command of nuclear ship any time.”

He placed his arm around the shoulders of Commander Ben Badr, and stated quietly, “Right now, I can say that in thirty years in the Russian Navy, I never met a better young submarine officer.”

“I’m feeling better about this by the minute,” said Ravi. “But I have one question…. What’s the range of our power accelerating?…Do we have two pumps, one for each turbine, with, presumably, slow and high speeds?”

“No,” said Ben, quickly. “We have six pumps. Very powerful. At low speeds we use two of them, working slowly. But we can have six of them, working fast, if we really want to get moving. That’s a big power range. This

Barracuda

can make over thirty-five knots under the water. Very hard to catch.”

General Rashood nodded, gazing back to where the watch keeper was checking the purity of the water. “That’s a key man, right there,” he said distractedly. “Two particles of sodium chloride per million, and he’s searching for them.”

“And remember the testing process,” said Ben. “We take a sample from the circuits frequently. And even the beaker we use must be surgically clean—in chemical terms, as clean as a hospital operating room.”

Ravi Rashood had stood among the supreme professionals of his trade before. But rarely had he experienced such a degree of confidence and efficiency as he sensed in this

Barracuda Type 945.

Captain Vanislav seemed to sense his thoughts. “We’re not supermen, General,” he said. “But we make fewer mistakes than most people. It goes with the territory. Mistakes down here can mean a very quick and somewhat unpleasant death. So, we tend not to make them.”

* * *

Five days and more than forty hours’ intensive study in the simulator had transformed General Ravi Rashood into a passable, theoretical submarine engineer. And now they were almost ready to go. In wide Kola Sound, downstream from Severomorsk, a small Navy escort out of Murmansk awaited the

Barracuda

on her final voyage under the command of Russia’s Northern Fleet.

One of the latest nuclear submarines, the

Gepard,

a nine thousand-ton Akula II, built in Severodvinsk and commissioned in 2004, was on the surface six miles east of the Cypnavolok headland. Two hundred yards off her port bow stood the frigate

Neustrashimy,

a four-year-old guided missile ship with an exceptional four thousand five hundred-mile range.

She was a Jastreb Class Type 1154, larger than the old Krivaks with the same turbine propulsion system as the Udaloys, but, like the Barracuda, she was very expensive. The Russians built only two of them, and then sold the third hull for scrap to pay outstanding debts.

The

Neustrashimy

was commissioned in the Baltic, but moved north a year later. Now she was bound for the Pacific Fleet and almost certainly would not return from Petropavlovsk.

One mile to the east, stark against the bright, low sun, which had only briefly dipped below the horizon all night, was the giant icebreaker

Ural,

This broad-shouldered, steel-hulled ruffian of the Arctic would lead the way as they moved across the gleaming but freezing blue waters of the northern ocean, avoiding or smashing the lingering ice floes, hugging the immense, bleak coastline of Siberia.

Back on the jetties of Araguba, a small crowd had gathered to watch the departure of their former

Barracuda

Class submarine

Tula.

General Ravi and Captain Vanislav stood with a Russian navigation officer on the bridge. Commander Badr, the Executive Officer, was below with the helmsman, another Russian veteran.

Deep in the Reactor Room, Lt. Comdr. Ali Akbar Mohtaj had observed the Russian Chief Petty Officer “pulling the rods,” bringing the reactor up to self-sustaining at the correct temperature and pressure. CPOs Ali Zahedi and Ardeshir Tikku were

positioned at two of the three panels in the reactor control room—Zahedi in propulsion, Tikku in auxiliary. Both men were now experienced in their areas of operation, and in overall command of the control area was the most senior of the Iranian submariners, Lt. Comdr. Abbas Shafii, who had been in Araguba for more than nine months.

Eight other Iranian Naval staff, four young Officers and four seasoned Chiefs, were also in the crew, occupying positions of serious responsibility in the turbine room and the air-cleansing plant. Two others had understudied the planesman, another worked in the electronics area. He was a Lieutenant Commander from Tehran, with two excellent degrees in electrical engineering, and three tours of duty in one of the Iranian Kilos.

All of the Iranians were dressed in the uniform of the People’s Liberation Army/Navy. And in addition there were fifteen Chinese members of the crew, five officers including a Lieutenant Commander who had been Missile Director in a large, absurdly noisy ICBM submarine out of Shanghai. Four Chiefs and six regular POs made up the number, and they were spread evenly through the ship mingling with the thirty Russians, and two interpreters who would often be working longer days than anyone.

Captain Vanislav called down through the communications system, “ATTEND BELLS!” And the Chief of Boat ordered the last dock line cast off.

The turbines came to life, and the huge propeller churned the water, as the jet black hull moved off the jetty, assisted by a tug; first in reverse, then sliding forward, on Vanislav’s command, “HALF-AHEAD.”

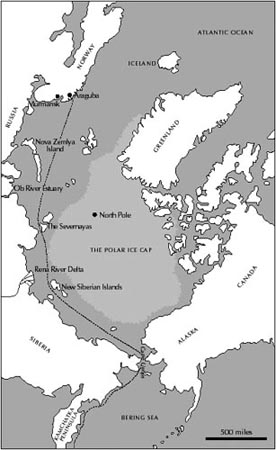

The Helmsman settled on to his ordered course north, straight at the Pole, 1,250 miles away. Ravi Rashood, standing on the bridge, felt on his face the winds off the Kola Peninsula, which now gusted out of the northwest, from across the vast ice cap that covers the top of the world, one thousand eight hundred miles in diameter.

They held course for only one mile as they stood down the outward channel from the sound, running fair through the short

sea, to make their rendezvous with the

Gepard

and the

Neustrashimy,

and then falling in behind the mighty

Ural.

THE ROUTE OF THE BARRACUDA FROM ARAGUBA

TO THE BERING STRAIT, SOUTH OF THE POLAR ICE CAP

Captain Vanislav called a course change to the northeast…

. Zero-four-two, half-ahead

…

make your speed twelve knots.

Up ahead they could see the colossal outline of the

Ural,

moving forward now, toward the outer edges of the Skolpen Bank, one of the shallow inshore shoals of the Barents Sea, where there’s only two hundred feet of water.

By 6

A

.

M

.,

Barracuda 945

was tucked in, three hundred yards astern of the icebreaker, with the frigate steaming on her starboard quarter, four hundred yards south of the

Gepard,

which was also on the surface.

Ahead of them stretched eight hundred miles of deep ocean, all the way to the northern headland of the rugged Novaya Zemlya islands, one a 460-mile-long, cresent-shaped island, only fifty miles wide. It looks like a forgotten extension of the Ural Mountains, which peter out just to the south, on the jagged hills of Vajgac Island. Almost certainly, when the mammoth roamed the tundra a million years ago, the Novaya Zemlya islands were actually joined to the mainland.

But right now it was not joined to anything, though in winter the pack-ice shelf sweeps right down to its seaward shores, but the North Cape Stream just manages to keep the tides flowing to the south.

Captain Vanislav’s two-hundred-mile-a-day journey passed without incident until they came toward a ten-mile-long ice field still floating, months after it had broken off the Arctic cap. The

Ural

’s Ops Room judged it still to be three to four feet thick, one hundred miles east of Novaya Zemlya.

Ravi and Ben both watched from the bridge as the icebreaker headed straight for the outer edge of the ice floe, and then drove right up onto the floating skating rink. Her reinforced bow rode up, almost one hundred feet beyond the water, and suddenly there was an almighty, echoing crack in the clear silent air, and then another, then six more, as the ice split asunder, forward and sideways, crushed beneath 23,500 tons of solid steel.

Into this newly created bay, the

Ural

drove forward until she

reached the end, and once more forced her way up onto the ice, her twin propellers ramming the stern forward another one hundred feet. Again there was the thunderous crack as a zillion tons of four-foot-thick ice split in half, causing a rift almost a quarter of a mile long.

“Christ,” said Ravi Rashood, staring in amazement at the sheer brute power of the

Ural.

“One more of those and we’re through.” He picked up his binoculars and stared ahead. The icebreaker seemed to be steaming through a bay now, with the floes splitting off on all sides.

He watched fascinated, as the

Ural

repeated her crushing assault on the remainder of the ice field, pulverizing the last couple of hundred yards seemingly without breaking stride, ramming the baby icebergs aside with that ironfisted bow; cleaving the way for the

Barracuda

and her consorts to reach the East Siberian Sea and on to the Bering Strait.

Clear of the ice pack, they rounded the seaward headland of Novaya Zemlya. They were due north of the estuary of Russia’s longest river, the 3,362-mile River Ob’, which rises in the hilly borders of Mongolia and then flows north right across the Siberian Plateau, east of the Urals, under the Trans-Siberian railroad bridge, and on into the icy depths of its fifty-mile-long hook-shaped estuary, twenty miles wide, all the way.

The end of Novaya Zemlya signaled the end of the Barents Sea, and now they entered the Kara Sea, which stretches another five hundred miles miles into the Severnaya Zemlya island group, two days away. There were no more ice floes, but well-charted shoals along the Central Kara Rise kept them well south, inshore, leaving the Nordenshel’da Archipelago to starboard as they made their easterly swerve through the narrow Strait of Vil’kitskogo, south of the Severnayas.

Which was where U.S. Surveillance first saw them clearly on photographs taken by “Big Bird” as it passed silently overhead.

A

.

M

., Thursday, August 9, 2007

National Security Agency

Fort Meade, Maryland

Lieutenant Ramshawe liked satellite photographs. However similar, however grainy, however routine they were, he looked forward to keying in through his computer to Intelink, the National Reconnaissance Office’s private Internet system of secure and encrypted cable networks. Jimmy could pick up surveillance photographs taken from anywhere in the world on the NRO-built constellation of satellites that endlessly circled the globe.

He always scrolled down to find anything of interest in the China Sea, and habitually had a look in the Bering Strait and along the Kamchatka Peninsula where the big Russian Pacific Fleet operates. He rarely, if ever, found anything worth researching, but that never stopped him looking. Ramshawe was one of the most natural-born Intelligence officers ever.

In summertime he always checked out any Naval activity in the seas to the east of the Severnayas. Up to that point the ocean was essentially Russian. They patrolled it, ran Navy exercises, and tested ships all along that coastline from way back in Murmansk for more than one thousand miles to the east of the Kola Peninsula.

Sometimes there were halfway interesting pictures, perhaps showing a new Russian warship, but mostly Jimmy found himself looking at the routine functions of a near moribund Navy. East of the Severnayas, however, was the place to spot fleet transfers, and it was important that the United States knew precisely where big Russian warships were stationed. Essential, in fact.