Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (23 page)

Earle Combs

The centerfielder and leadoff hitter for the team many people still consider to be the greatest in baseball history—the 1927 New York Yankees—was Earle Combs. He played 12 seasons for the Yankees, from 1924 to 1935, but that 1927 season was his finest. Combs established career-highs in batting average (.356), hits (231), and triples (23) that magical year, while also scoring 137 runs and fulfilling his role as leadoff hitter better than perhaps anyone else in the game. He also had outstanding seasons in 1925, 1929, 1930, and 1932, never batting any lower than .321 or scoring less than 117 runs in any of those seasons, and scoring a career-high 143 runs in 1932.

During his career, Combs led the American League in triples three times and in hits once. He finished with more than 20 triples three times, batted over .300 ten times, topping the .340-mark on four separate occasions, collected more than 200 hits three times, and scored more than 100 runs eight times. In each of his nine full seasons, he finished in double-digits in triples.

The problem with Combs, though, was that he was a full-time player for only those nine seasons. His career was relatively short, and in three of his 12 seasons, he failed to accumulate as many as 300 at-bats, totaling only 417 plate appearances in a fourth campaign. A player with such a short career must be truly dominant in order to be thought of as a legitimate Hall of Fame candidate. While Combs was a fine player, he was not a dominant one. He was never considered to be among the very best players in the game, or even in his own league. He was the best centerfielder in the American League in only 1925 and 1927, being ranked behind Earl Averill for most of his career, and he was never thought to be the best player in the game at his position. Combs finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting only once, and he was a league-leader in a major offensive category only four times. In addition, playing in an era during which big offensive numbers were rather commonplace, he had only five seasons that even remotely resembled those of a legitimate Hall of Famer. His offensive numbers were somewhat inflated by the era in which he played, and by the team for which he played. Combs’ status as New York’s leadoff hitter enabled him to precede Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in the Yankee lineup for virtually his entire career. Batting in front of two of the greatest run-producers in the history of the game unquestionably enabled Combs to score many more runs than he otherwise would have.

There is also little doubt that the aura of the 1927 Yankees contributed significantly to Combs’ selection by the Veterans Committee in 1970. There is no question that Combs had an integral role on that team, and that he was a very good player. But his career was too short, and he was not dominant enough to allow us to overlook that last fact. Therefore, his selection by the Committee was one that probably should never have been made.

Lloyd Waner

Prior to both players being dealt to other clubs at the end of the 1940 season, Lloyd Waner spent 14 years playing alongside his older brother Paul in the Pittsburgh Pirates’ outfield. While Paul usually batted either third or fourth in the Pirates’ lineup, Lloyd was the leadoff hitter for much of his career, and was one of the better ones in the game.

The younger of the Waner brothers batted over .300 ten times, finishing his career with a .316 batting average. He collected more than 200 hits four times and scored more than 100 runs three times. He led the National League in hits, runs scored, and triples once each. Waner’s first three seasons were his best. In 1927, he batted .355, scored 133 runs, and collected 223 hits. The following year, he finished with a batting average of .335, 121 runs scored, and 221 base hits. Waner had probably his finest season in 1929, though. That year, he batted .353 and established career-highs in runs scored (134), hits (234), triples (20), and runs batted in (74).

Those first three seasons, however, turned out to be the only truly exceptional ones Waner had during his career. Playing mostly during a hitter’s era, he never again batted any higher than .333, scored more than 90 runs, or knocked in more than 57 runs, and he had only one other season with more than 200 hits. Waner had absolutely no power, never hitting more than five home runs in a season, and he stole only 67 bases during his career. In addition, due to the fact that he hardly ever walked (his single-season high was only 40), his career on-base percentage was a modest .349— not particularly high for a leadoff hitter. As a result, he was not an exceptionally good run-producer.

Waner was never considered to be one of the very best players in his league, and he was never thought to be among the top two or three centerfielders in the game. He finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting only one time, and he was generally considered to be only the third or fourth best player on his own team (behind his brother, Paul, Pie Traynor, and, later, Arky Vaughan).

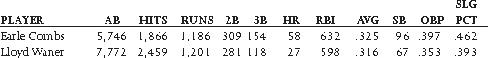

If the selection of Earle Combs to the Hall of Fame was not a particularly good one, Waner’s selection was downright puzzling. Take a look at the career numbers of both players:

The two men played at essentially the same time, albeit in different leagues. While it is true that Combs had a better supporting cast in New York, the Pirate teams that Waner played for usually had a potent lineup as well. In approximately 2,000 fewer at-bats, Combs finished well ahead of Waner in virtually every offensive category. He was clearly the better player of the two. Therefore, if Combs’ selection is looked upon as being a bad one, what does that say for the selection of Waner? He clearly does not belong in the Hall of Fame.

Babe Ruth/Hank Aaron

Ruth and Aaron were not only the two greatest rightfielders in the history of the game, but were among the very greatest players in baseball history.

Babe Ruth was the greatest, most dominant player of all time. He dominated his era as no other player ever has, and he was undoubtedly the most famous player who ever lived. Perhaps the most amazing thing about Ruth, though, is that if he hadn’t been converted from a starting pitcher into an outfielder early in his career to take greater advantage of his hitting skills, he likely would have eventually made it into the Hall of Fame as a

pitcher.

After all, starting for the Boston Red Sox from 1916 to 1918, Ruth was acknowledged to be the best lefthanded pitcher in the game. However, it was as a hitter that he gained his greatest fame.

Ruth was the greatest offensive performer the game has ever seen, setting numerous records, most of which have since been broken. No other player has, by himself, hit more home runs in a season than

entire teams

, a feat that Ruth accomplished on more than one occasion. From 1918 to 1931, he led the American League in home runs and slugging percentage 12 times each, in runs batted in six times, in batting average once, in runs scored eight times, in walks 11 times, and in on-base percentage 10 times. He ranks among the all-time leaders in home runs, runs batted in, runs scored, batting average, walks, and on-base percentage, and his career slugging percentage of .690 is 56 points higher than that of Ted Williams, who, at .634, is second on the all-time list.

Ruth missed extensive playing time in 1922 due to a suspension, and again in 1925, due to an illness. However, in every other season from 1920 to 1931, he was either the very best player in the game, or among the top two or three. He won an MVP Award and was selected to

The Sporting News All-Star Team

each season from 1926 to 1931, the first six years that publication announced its selections. No other player deserves to be in the Hall of Fame more than Ruth.

For quite some time, Hank Aaron was one of the most overlooked superstars ever to play in the major leagues. His low-key personality certainly contributed to his virtual anonymity, as did the fact that he spent the first half of his career playing in Milwaukee, while contemporaries Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle performed in much larger media markets. Only towards the end of his career as he drew inexorably closer to Babe Ruth’s cherished home run record did Aaron begin to garner the attention he so richly deserved. It was also only then that people began to realize that he was one of the five greatest players who ever lived.

Aaron’s name is all over the record books: first all-time in runs batted in and total bases; second in home runs, third in runs scored and base hits; ninth in doubles. While he never had one particular year that could be identified as his signature season, Aaron was a study in long-term excellence, putting up outstanding numbers year after year. Aaron led the National League in home runs, runs batted in, doubles, and slugging percentage four times each, in runs scored three times, and in batting average and base hits twice each. He was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1957, when he led the Braves to the world championship by leading the league in homers (44), runs batted in (132), and runs scored (118), while batting .322. He finished in the top five in the MVP voting seven other times.

Aaron was a superb player for virtually his entire career, and he was one of the five best players in baseball from 1957 to 1971. In several of those seasons, he was the best player in the game. He was particularly outstanding in 1957, 1959, 1960, 1962, 1963, 1966, 1967, and 1971. In each of those years, Aaron knocked in well over 100 runs, compiled a batting average that either approached or exceeded .300, hit no fewer than 39 homers, and scored over 100 runs (except for 1971, when he crossed the plate 95 times). Unfortunately, it seems that only over the past two decades have people come to realize how great a player Hank Aaron was.

Frank Robinson/Roberto Clemente

Robinson and Clemente were also superb players whose Hall of Fame credentials would not be questioned by anyone.

While Hank Aaron’s excellence was overlooked for much of his career, Frank Robinson is someone who still does not get the credit he deserves for being one of the greatest players in baseball history. Robinson is sixth on the all-time home run list, with 586, and he also ranks in the top 10 in total bases. He finished his career with 1,812 runs batted in, 1,829 runs scored, and 2,943 hits. Even in this age of free agency when players change teams and leagues so frequently, Robinson remains the only player in baseball history to win the Most Valuable Player Award in each league. During his career, Robinson finished in the top five in the MVP voting a total of six times. He was also a 12-time All-Star.

Robinson was one of the best players in the game in virtually every season from his rookie year of 1956 to 1969. His most outstanding years were 1959, 1961, 1962, 1965, and 1966—all seasons in which he was among the two or three best players in baseball. In each of those campaigns, he hit no fewer than 33 home runs, knocked in well over 100 runs, batted well over .300 (except for 1965, when he batted .296), and scored well over 100 runs. In his first MVP season of 1961, he was the league’s best player as he led the Cincinnati Reds to the National League pennant by hitting 37 homers, knocking in 124 runs, and batting .323. The following year, his numbers were even better as he hit 39 homers, drove in 136 runs, batted .342, and led the league with 51 doubles, 134 runs scored, an on-base percentage of .424, and a slugging percentage of .624. Robinson was baseball’s greatest player in 1966, after switching leagues prior to the start of the season. He captured the American League triple crown and his second Most Valuable Player Award en route to leading the Baltimore Orioles to the world championship. That year, Robinson led the league with 49 homers, 122 RBIs, a .316 batting average, 122 runs scored, an on-base percentage of .415, and a slugging percentage of .637.

In addition to being a great player, Robinson was also an exceptional team leader and a fierce competitor. Although he is not always viewed as such, Robinson was one of the 15 greatest position players in the history of the game.

For virtually all of the 1960s, and even into the early ’70s, Roberto Clemente was one of the five best players in baseball. He finished the decade of the sixties with the highest batting average of any player during that ten-year period, with a mark of .328. During his career, Clemente won four batting titles, hitting over .350 three times, and topping the .340 mark two other times. He batted over .300 in 14 of his 18 big league seasons, finishing his career with a .317 batting average. He also collected 3,000 hits, compiling as many as 200 safeties in a season four times, and leading the league in that department twice.

Though somewhat overshadowed earlier in his career by Hank Aaron, Al Kaline, Roger Maris, and Frank Robinson, by the midsixties Clemente established himself as a truly great player who only Aaron and Robinson could challenge for supremacy among major league rightfielders. Although Robinson was the best player in the game in 1966, Clemente was a close second. Establishing career highs in home runs (29), runs batted in (119), and runs scored (105), while also batting .317 that year, Clemente was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. The following year, he finished in the top five in the MVP voting once more, and only Carl Yastrzemski’s triple crown season for the Red Sox prevented him from being the best player in baseball. That season, Clemente finished with 23 home runs, 110 runs batted in, 103 runs scored, 209 hits, and a major league leading batting average of .357. In all, he finished in the top five in the MVP voting four times during his career.

Of course, Clemente was more than just a great hitter. He was perhaps the finest defensive rightfielder in baseball history. He had great range and a powerful and accurate throwing arm. During his career, Clemente was the winner of 12 straight Gold Gloves; only Al Kaline rivaled him defensively among players at the position. In addition, Clemente was a tremendous postseason performer. He hit safely in each of the 14 World Series games in which he played, leading the Pirates to Series victories in 1960, over the Yankees, and in 1971, over the Orioles. In that 1971 Series, Clemente hit two homers, batted .414, had 12 hits, and gave a memorable performance in rightfield to earn Series MVP honors.

Harry Heilmann

Many players posted impressive offensive numbers during the hitting-dominated 1920s. However, one player whose numbers surpassed those of almost every other major leaguer during that period was the Detroit Tigers’ Harry Heilmann. From 1921 to 1927, Heilmann was one of the four or five best players in the American League, and one of the very best players in baseball. With the exception of Babe Ruth, he was the best rightfielder in the game over that stretch. In fact, with Ruth missing good portions of both the 1922 and 1925 seasons, Heilmann was the best player at that position in each of those years. During that seven-year period, he won four batting titles, never hit less than .346, topped the .390 mark four times, and batted over .400 once. He also led the league in doubles and hits one time each.

During his career, Heilmann knocked in over 100 runs eight times, and he also scored more than 100 runs four times. He finished in double-digits in triple nine times, collected more than 40 doubles eight times, and amassed more than 200 hits four times. He finished his career with 183 home runs, 1,539 runs batted in, 1,291 runs scored, 151 triples, 542 doubles, and a superb .342 batting average. He also fared well in the MVP voting, finishing in the top 10 five times and placing in the top five on four separate occasions.

While it is true that Heilmann’s numbers were somewhat inflated by playing predominantly during a hitter’s era, it is also true that he was one of the most outstanding hitters of that era, and one of the best players of his day. His election to Cooperstown, therefore, is one that cannot be questioned.

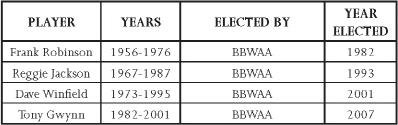

Tony Gwynn

In his 20 seasons with the San Diego Padres, Tony Gwynn established himself as the finest scientific hitter of his era, and as one of the best ever. He finished his career with 3,141 base hits and a batting average of .338, the highest of any player whose career began after 1940, and the highest since Ted Williams retired with a mark of .344. During his career, Gwynn won seven batting titles and also led the National League in hits six times, and in runs scored twice. Gwynn batted over .350 seven times and collected more than 200 hits five times. He was not a tremendous run-producer, having surpassed the 100-RBI mark only once, and topping 100 runs scored only twice in his 20 big-league seasons. However, the fact that the Padres were a mediocre team for most of Gwynn’s career is largely responsible for his inability to compile huge numbers in either of those offensive categories.