Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (127 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

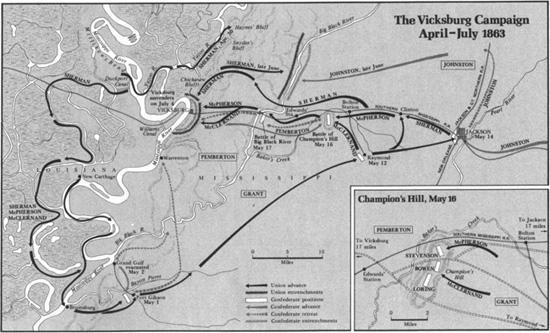

Thus had Grant wrought in a seventeen-day campaign during which his army marched 180 miles, fought and won five engagements against separate enemy forces which if combined would have been almost as large as his own, inflicted 7,200 casualties at the cost of 4,300, and cooped up an apparently demoralized enemy in the Vicksburg defenses. Of all the tributes Grant received, the one he appreciated most came from his friend Sherman. "Until this moment I never thought your expedition a success," Sherman told Grant on May 18 as he gazed down from the heights where his corps had been mangled the previous December. "I never could see the end clearly until now. But this is a campaign. This is a success if we never take the town."

6

But Grant hoped to take the town, immediately, while its defenders were still stunned. Without stopping to rest, he ordered an attack by his whole army on May 19. With confidence bred by success, northern boys charged the maze of trenches, rifle pits, and artillery ringing the landward side of Vicksburg. But as they emerged into the open the rebel line came alive with sheets of fire that stopped the bluecoats in their tracks. Ensconced behind the most formidable works of the war, the rebels had taken heart. They proved the theory that one soldier under cover was the equal of at least three in the open.

Bloodied but still undaunted, the Union troops wanted to try again. Grant planned another assault for May 22, preceded this time by reconnaisance to find weak points in enemy lines (there were few) and an artillery bombardment by 200 guns on land and 100 in the fleet. Again the Yankees surged forward against a hail of lead, this time securing lodgement at several points only to be driven out by counterattacks. After several hours of this, McClernand on the Union left sent word of a breakthrough and a request for support to exploit it. Distrustful as ever of McClernand, Grant nevertheless ordered Sherman and McPherson to renew their attacks and send reinforcements to the left. But these

5

. Quoted in Walker,

Vicksburg

, 161.

6

. Quoted in Carter,

Final Fortress

, 208.

efforts, said Grant later, "only served to increase our casualties without giving any benefit."

7

For the second time in four days the southerners threw back an all-out attack, doing much to redeem their earlier humiliation and inflicting almost as many casualties on the enemy as in all five earlier clashes combined.

Though they failed, Grant did not consider these assaults a mistake. He had hoped to capture Vicksburg before Johnston could build up a relief force in his rear and before summer heat and disease wore down his troops. Moreover, he explained, the men "believed they could carry the works in their front, and they would not [afterwards] have worked so patiently in the trenches if they had not been allowed to try."

8

After the May repulses the bluecoats dug their own elaborate network of trenches and settled down for a siege. Grant called in reinforcements from Memphis and other points to build up his army to 70,000. He posted several divisions to watch Johnston, who was now hovering off to the northeast with a makeshift army of 30,000, some of them untrained conscripts. Grant had no doubt of ultimate success. On May 24 he informed Halleck that the enemy was "in our grasp. The fall of Vicksburg and the capture of most of the garrison can only be a question of time."

9

Pemberton thought so too, unless help arrived. Regarding Vicksburg as "the most important point in the Confederacy," he informed Johnston in a message smuggled through Federal lines by a daring courier that he intended to hold it "as long as possible." But Pemberton could hold on only if Johnston pierced the blue cordon constricting him. "The men credit and are encouraged by a report that you are near with a large force." For the next six weeks Pemberton's soldiers and some three thousand civilians trapped in Vicksburg lived in hope of rescue by Johnston. "We certainly are in a critical situation," wrote a southern army surgeon, but "we can hold out until Johnston arrives with reinforcements and attacks Yankees in rear. . . . Davis can't intend to sacrifice us."

10

But Davis had no more reinforcements to send. Braxton Bragg had already lent Johnston two divisions and could not spare another. Robert E. Lee insisted that he needed every soldier in Virginia for his impending invasion of Pennsylvania. In Louisiana, General Richard Taylor

7

. Grant,

Memoirs

, I, 531.

8

.

Ibid.

, 530–31.

9

. Quoted in Foote,

Civil War

, II, 388.

10

.

Ibid.

, 387; Carter,

Final Fortress

, 207, 223.

(son of Mexican War hero Zachary Taylor) reluctantly diverted three brigades from his campaign against Banks to assist Pemberton. Their only accomplishment, however, was to publicize the controversy surrounding northern employment of black troops. In a futile attempt to disrupt Grant's restored supply line, one of Taylor's brigades on June 7 attacked the Union garrison at Milliken's Bend on the Mississippi above Vicksburg. This post was defended mainly by two new regiments of contrabands. Untrained and armed with old muskets, most of the black troops nevertheless fought desperately. With the aid of two gunboats they finally drove off the enemy. For raw troops, wrote Grant, the freed-men "behaved well." Assistant Secretary of War Dana, still with Grant's army, spoke with more enthusiasm. "The bravery of the blacks," he declared, "completely revolutionized the sentiment of the army with regard to the employment of negro troops. I heard prominent officers who formerly in private had sneered at the idea of negroes fighting express themselves after that as heartily in favor of it."

11

But among the Confederates, Dana added, "the feeling was very different." Infuriated by the arming of former slaves, southern troops at Milliken's Bend shouted "no quarter!" and reportedly murdered several captured blacks. If true, such behavior undoubtedly reflected their officers' sentiment: the rebel brigade commander "consider[ed] it an unfortunate circumstance that any negroes were captured," while General Taylor reported that "a very large number of the negroes were killed and wounded, and, unfortunately, some 50, with 2 of their white officers, captured." The War Department in Washington learned that some of the captured freedmen were sold as slaves.

12

The repulse at Milliken's Bend cut short Confederate attempts to succor Vicksburg from west of the Mississippi. All hopes for relief now focused on Johnston. The Vicksburg newspaper (reduced in size to a square foot and printed on wallpaper) buoyed up spirits with cheerful predictions: "The undaunted Johnston is at hand"; "We may look at any hour for his approach"; "Hold out a few days longer, and our lines will be opened, the enemy driven away, the siege raised."

13

During the first month of the siege, morale remained good despite around-the-clock

11

. Grant,

Memoirs

, I, 545; Charles A. Dana,

Recollections of the Civil War

(New York, 1899), 86.

12

.

O.R.

, Ser. I, Vol. 24, pt. 2, pp. 466, 459.

13

. Walker,

Vicksburg

, 187–88.

Union artillery and gunboat fire that drove civilians into man-made caves that dotted the hillsides.

But as the weeks passed and Johnston did not come, spirits sagged. Soldiers were subsisting on quarter rations. By the end of June nearly half of them were on the sicklist, many with scurvy. Skinned rats appeared beside mule meat in the markets. Dogs and cats disappeared mysteriously. The tensions of living under siege drove people to the edge of madness: if things went on much longer, wrote a Confederate officer, "a building will have to be arranged for the accommodation of maniacs." The tone of the newspaper changed from confidence to complaint: in the last week of June it was no longer "Johnston is coming!" but "Where is Johnston?"

14

Johnston had never shared the belief in himself as Deliverer. "I consider saving Vicksburg hopeless," he informed the War Department on June 15. To the government this looked like a western refrain of Johnston's behavior on the Virginia Peninsula in 1862, when he had seemed reluctant to fight to defend Richmond. "Vicksburg must not be lost without a desperate struggle," the secretary of war wired back. "The interest and the honor of the Confederacy forbid it. . . . You must hazard attack. . . . The eyes and hopes of the whole Confederacy are upon you."

15

But Johnston considered his force too weak. He shifted the burden to Pemberton, urging him to try a breakout attack or to escape across the river (through the gauntlet of Union ironclads!). At the end of June, in response to frantic pressure from Richmond, Johnston began to probe feebly with his five divisions toward seven Union divisions commanded by Sherman which Grant had detached from the besiegers to guard their rear. Johnston's rescue attempt was too little and too late. By the time he was ready to take action, Pemberton had surrendered.

Inexorable circumstances forced Pemberton to this course—though many southerners then and later believed that only his Yankee birth could have produced such poltroonery. All through June, Union troops had dug approaches toward Confederate lines in a classic siege operation. They also tunneled under rebel defenses. To show what they could do, northern engineers exploded mines and blew holes in southern lines

14

. Bruce Catton,

Never Call Retreat

(New York: Pocket Books ed., 1967), 195–96; Walker,

Vicksburg

, 192–96.

15

.

O.R

., Ser. I, Vol. 24, pt. 1, pp. 227–28.

on June 25 and July 1, but Confederate infantry closed the breaches. The Yankees readied a bigger mine to be set off July 6 and followed by a full-scale assault. But before then it was all over. Literally starving, "Many Soldiers" addressed a letter to Pemberton on June 28: "If you can't feed us, you had better surrender, horrible as the idea is, than suffer this noble army to disgrace themselves by desertion. . . . This army is now ripe for mutiny, unless it can be fed."

16

Pemberton consulted his division commanders, who assured him that their sick and malnourished men could not attempt a breakout attack. On July 3, Pemberton asked Grant for terms. Living up to his Donelson reputation, Grant at first insisted on unconditional surrender. But after reflecting on the task of shipping 30,000 captives north to prison camps when he needed all his transport for further operations, Grant offered to parole the prisoners.

17

With good reason he expected that many of them, disillusioned by suffering and surrender, would scatter to their homes and carry the contagion of defeat with them.

The Fourth of July 1863 was the most memorable Independence Day in American history since that first one four score and seven years earlier. Far away in Pennsylvania the high tide of the Confederacy receded from Gettysburg. Here in Mississippi, white flags sprouted above rebel trenches, the emaciated troops marched out and stacked arms, and a Union division moved into Vicksburg to raise the stars and stripes over the courthouse. "This was the most Glorious Fourth I ever spent," wrote an Ohio private. But to many southerners the humiliation of surrendering on July 4 added insult to injury. The good behavior of the occupation troops, however, mitigated the insult. Scarcely a taunt escaped their lips as Union soldiers marched into the city; on the contrary, they paid respect to the courage of the defenders and shared rations with them. Indeed, the Yankees did what many Vicksburg citizens had wanted to do for weeks—they broke into the stores of "speculators" who had been holding food for higher prices. As described by a Louisiana sergeant, northern soldiers brought these "luxuries" into the streets "and throwing them down, would shout, 'here rebs, help yourselves, you are naked