Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (22 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

Some evidence points to the South's agrarian value system as an important reason for lack of industrialization. Although the light of Jeffer-sonian egalitarianism may have dimmed by 1850, the torch of agrari-anism still glowed. "Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God . . . whose breasts He has made His peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue," the husbandman of Monticello had written. The proportion of urban workingmen to farmers in any society "is the proportion of its unsound to its healthy parts" and adds "just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body."

43

The durability of this conviction in the South created a cultural climate unfriendly to industrialization. "In cities and factories, the vices of our nature are more fully displayed," declared James Hammond of South Carolina in 1829, while rural life "promotes a generous hospitality, a high and perfect courtesy, a lofty spirit of independence . . . and all the nobler virtues and heroic traits." An Englishman traveling through the South in 1842 found a widespread feeling "that the labours of the people should be confined to agriculture, leaving manufactures to Europe or to the States of the North."

44

Defenders of slavery contrasted the bondsman's comfortable lot with the misery of wage slaves so often that they began to believe it. Beware

41

. Kenneth M. Stampp,

The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South

(New York, 1956); Alfred H. Conrad and John R. Meyer, "The Economics of Slavery in the Ante Bellum South,"

Journal of Political Economy

, 66 (1958), 95–130; Fogel and Engerman,

Time on the Cross

.

42

. Alfred H. Conrad et al., "Slavery as an Obstacle to Economic Growth in the United States: A Panel Discussion,"

Journal of Economic History

, 27 (1967), 518–60; Gavin Wright,

The Political Economy of the Cotton South

(New York, 1978); Fred Bateman and Thomas Weiss, A

Deplorable Scarcity: The Failure of Industrialization in the Slave Economy

(Chapel Hill, 1981).

43

.

Notes on the State of Virginia

, ed. William Peden (Chapel Hill, 1955), 164–65.

44

. Hammond quoted in Orville Vernon Burton,

In My Father's House Are Many Mansions: Family and Community in Edgefield, South Carolina

(Chapel Hill, 1985), 37; James S. Buckingham,

The Slave States of America

, 2 vols. (London, 1842), II, 112.

of the "endeavor to imitate . . . Northern civilization" with its "filthy, crowded, licentious factories," warned a planter in 1854. "Let the North enjoy their hireling labor with all its . . . pauperism, rowdyism, mob-ism and anti-rentism," said the collector of customs in Charleston. "We do not want it. We are satisfied with our slave labor. . . . We like old things—old wine, old books, old friends, old and fixed relations between employer and employed."

45

By the later 1850s southern agrarians had mounted a counterattack against the gospel of industrialization. The social prestige of planters pulled other occupations into their orbit rather than vice versa. "A large plantation and Negroes are the

ultima Thule

of every Southern gentleman's ambition," wrote a frustrated Mississippi industrial promoter in 1860. "For this the lawyer pores over his dusty tomes, the merchant measures his tape . . . the editor drives his quill, and the mechanic his plane—all, all who dare to aspire at all, look to this as the goal of their ambition." After all, trade was a lowly calling fit for

Yankees

, not for gentlemen. "That the North does our trading and manufacturing mostly is true," wrote an Alabamian in 1858, "and we are willing that they should. Ours is an agricultural people, and God grant that we may continue so. It is the freest, happiest, most independent, and with us, the most powerful condition on earth."

46

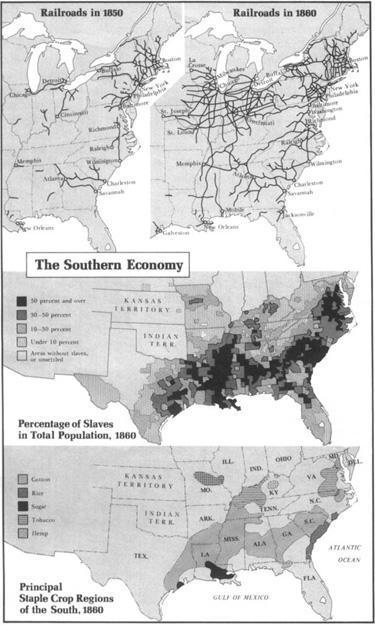

Many planters did invest in railroads and factories, of course, and these enterprises expanded during the 1850s. But the trend seemed to be toward even greater concentration in land and slaves. While per capita southern wealth rose 62 percent from 1850 to 1860, the average price of slaves increased 70 percent and the value per acre of agricultural land appreciated 72 percent, while per capita southern investment in manufacturing increased only 39 percent. In other words, southerners had a larger portion of their capital invested in land and slaves in 1860 than in 1850.

47

45

. "The Prospects and Policy of the South, as They Appear to the Eyes of a Planter,"

Southern Quarterly Review

, 26 (1854), 431–32; William J. Grayson,

Letters of Curtius

(Charleston, 1852), 8.

46

.

Vicksburg Sun

, April 9, 1860; Alabamian quoted in Russel,

Economic Aspects of Southern Sectionalism

, 207.

47

. During the same period the per capita wealth of northerners increased 26 percent and per capita northern investment in industry rose 38 percent. Data on per capita wealth are from Soltow,

Men and Wealth

, 67; data on the price of slaves are from Phillips,

American Negro Slavery

, 371; all other data cited here have been compiled from the published census returns of 1850 and 1860.

Although the persistence of Jeffersonian agrarianism may help explain this phenomenon, the historian can discover pragmatic reasons as well. The 1850s were boom years for cotton and for other southern staples. Low cotton prices in the 1840s had spurred the crusade for economic diversification. But during the next decade the price of cotton jumped more than 50 percent to an average of 11.5 cents a pound. The cotton crop consequently doubled to four million bales annually by the late 1850s. Sugar and tobacco prices and production similarly increased. The apparent insatiable demand for southern staples caused planters to put every available acre into these crops. The per capita output of the principal southern food crops actually declined in the 1850s, and this agricultural society headed toward the status of a food-deficit region.

48

Although these trends alarmed some southerners, most expressed rapture over the dizzying prosperity brought by the cotton boom. The advocates of King Commerce faded; King Cotton reigned supreme. "Our Cotton is the most wonderful talisman in the world," declared a planter in 1853. "By its power we are transmuting whatever we choose into whatever we want." Southerners were "unquestionably the most prosperous people on earth, realizing ten to twenty per cent on their capital with every prospect of doing as well for a long time to come," boasted James Hammond. "The slaveholding South is now the controlling power of the world," he told the Senate in 1858. "Cotton, rice, tobacco, and naval stores command the world. . . . No power on earth dares . . . to make war on cotton. Cotton is king."

49

By the later 1850s southern commercial conventions had reached the same conclusion. The merger of this commercial convention movement with a parallel series of planters' conventions in 1854 reflected the

48

. The production of corn, sweet potatoes, and hogs in the slave states decreased on a per capita basis by 3, 15, and 22 percent respectively from 1850 to 1860. The possibility that southerners were becoming a beef-eating people does not seem a satisfactory explanation for the per capita decrease of hogs. The number of cattle per capita in the South increased only 3 percent during the decade, and according to Robert R. Russel virtually all of this increase was in dairy cows, not beef cattle. Russel,

Economic Aspects of Southern Sectionalism

, 203. The data in this paragraph, compiled mainly from the published census returns of 1850 and 1860, are conveniently available in tabular form in Schlesinger, ed.,

History of American Presidential Elections

, II, 1128 ff.

49

. Planter quoted in John McCardell,

The Idea of a Southern Nation

:

Southern Nationalists and Southern Nationalism, 1830–1860

(New York, 1979), 134; Hammond to William Gilmore Simms, April 22, 1859, quoted in Nevins,

Emergence

, I, 5;

CG

, 35 Cong., 1

Sess

., 961–62.

trend. Thereafter slave agriculture and its defense became the dominant theme of the conventions. Even

De Bow's Review

moved in this direction. Though De Bow continued to give lip service to industrialization, his

Review

devoted more and more space to agriculture, proslavery polemics, and southern nationalism. By 1857 the politicians had pretty well taken over these "commercial" conventions. And the main form of commerce they now advocated was a reopening of the African slave trade.

50

Federal law had banned this trade since the end of 1807. Smuggling continued on a small scale after that date; in the 1850s the rising price of slaves produced an increase in this illicit traffic and built up pressure for a repeal of the ban. Political motives also actuated proponents of repeal. Agitation of the question, said one, would give "a sort of spite to the North and defiance of their opinions." A delegate to the 1856 commercial convention insisted that "we are entitled to demand the opening of this trade from an industrial, political, and constitutional consideration. . . . With cheap negroes we could set the hostile legislation of Congress at defiance. The slave population after supplying the states would overflow into the territories, and nothing could control its natural expansion." For some defenders of slavery, logical consistency required a defense of the slave trade as well. "Slavery is right," said a delegate to the 1858 convention, "and being right there can be no wrong in the natural means of its formation." Or as William L. Yancey put it: "If it is right to buy slaves in Virginia and carry them to New Orleans, why is it not right to buy them in Africa and carry them there?"

51

Why not indeed? But most southerners failed to see the logic of this argument. In addition to moral repugnance toward the horrors of the "middle passage" of slaves across the Atlantic, many slaveowners in the upper South had economic reasons to oppose reopening of the African trade. Their own prosperity benefitted from the rising demand for slaves; a growing stream of bondsmen flowed from the upper South to the cotton states. Nevertheless, the commercial convention at Vicksburg in 1859 (attended by delegates from only the lower South) called for repeal

50

. McCardell,

Idea of a Southern Nation

, 129–40; Otis Clark Skipper, J. D. B.

De Bow: Magazinist of the Old South

(Athens, Ga., 1958), 81–97; Wender,

Southern Commercial Conventions

, 207, 225.

51

. Potter,

Impending Crisis

, 398–99; Wender,

Southern Commercial Conventions

, 178, 213.

of the ban on slave imports. Proponents knew that they had no chance of success in Congress. But they cared little, for most of them were secessionists who favored a southern nation that could pass its own laws. In the meantime they could try to circumvent federal law by bringing in "apprentices" from Africa. De Bow became president of an African Labor Supply Association formed for that purpose. In 1858 the lower house of the Louisiana legislature authorized the importation of such apprentices. But the senate defeated the measure.

52