Battleship Bismarck (50 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

After a while, we survivors were led to the wardroom, where we sat around a big table and were given hot tea. We were still numb and not very talkative, but the tea helped. When we had finished, Kapitänleutnant (Ing) Junack, Fähnrich (B) Hans-Georg Stiegler, Nautischer Assistent

*

Lothar Balzer, and I—just four of the

Bismarck’s

ninety

officers—were taken aft to our allotted quarters. The eighty-one petty officers and men were taken forward.

That afternoon we rested. I lay on my bunk in a strange state between sleep and wakefulness. I could not take in all the terrible things that had happened in the last few hours. Did they really happen? Somehow, my mind rejected the thought; no one could have survived that devastating storm of steel. So many good men had been lost. Why they and not I? I knew only that God had heard me on the upper deck of the

Bismarck

.

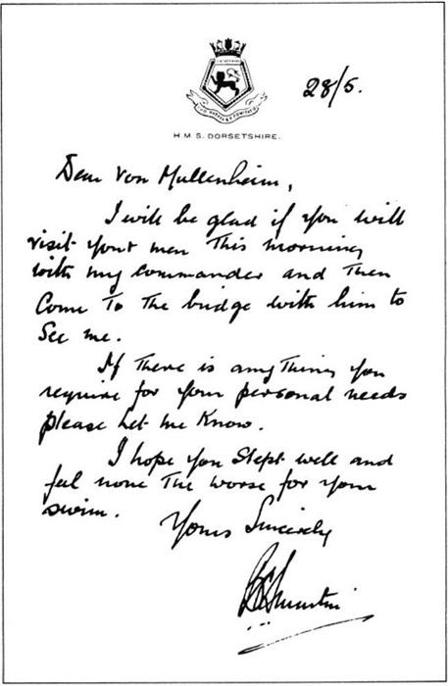

As the senior-ranking survivor on board, I received the next morning a handwritten note from Captain B. C. S. Martin, the commanding officer of the

Dorsetshire:

I will be glad if you will visit your men this morning with my commander and then come to the bridge with him to see me.

If there is anything you require for your personal needs please let me know.

I hope you slept well and feel none the worse for your swim.

Escorted by the First Officer, Commander C. W. Byas, I went to see how our men were getting along. Everything was satisfactory; the ship’s surgeon was taking care of the sick and injured, and they all felt they were being treated very well. They were getting five meals a day and eating the same excellent food as the crew. The smokers among them were being issued twenty cigarettes a day. I learned later that it was no different in the

Maori

, which picked up twenty-five men, bringing the number rescued by British ships to 110, about 5 percent of the more than 2,200 on board.

When Byas took me to the bridge, Captain Martin greeted me in a friendly enough manner and gave me a Scotch. The gesture was well meant but I was still too horrified at his leaving all those men in the water the day before to really appreciate it. “Why,” I burst out, “did you suddenly break off the rescue and leave hundreds of our men to drown?” Martin replied that a U-boat had been sighted or at least reported, and he obviously could not endanger his ship by staying stopped any longer. The

Bismarck’s

experiences on the night of 26 May and the morning of the 27th, I told him, indicated that there were no U-boats in the vicinity. Farther away, perhaps, but certainly not within firing range of the

Dorsetshire

. I added that in war one often sees what one expects to see. And so we heaped our arguments against one another, uncompromisingly, beyond any possibility of

agreement. Martin brought our discussion brusquely to a close with the words: “Just leave that to me. I’m older than you are and have been at sea longer. I’m a better judge.” What more could I say? He was the captain and was responsible for his ship.

*

Apparently some floating object had been mistaken for a periscope or a strip of foam on the water for the wake of a torpedo. No matter what it was, I am now convinced that, under the circumstances, Martin had to act as he did.

†

At 1100 on 27 May Churchill informed the House of Commons of the final action against the

Bismarck

. “This morning,” he said, “shortly after daylight the

Bismarck

, virtually at a standstill, far from help, was attacked by the British pursuing battleships. I do not know what were the results of the bombardment. It appears, however, that the

Bismarck

was not sunk by gunfire, and she will now be dispatched by torpedo. It is thought that this is now proceeding, and it is also thought that there cannot be any lengthy delay in disposing of this vessel. Great as is our loss in the

Hood

, the

Bismarck

must be regarded as the most powerful, as she is the newest, battleship in the world.” Scarcely had Churchill sat down when a note was passed to him. He rose again and announced to the members that the

Bismarck

had been sunk. “They seemed content,” he wrote.

*

A day later he telegraphed Roosevelt: “I will send you later the inside story of the fighting with the

Bismarck

. She was a terrific ship, and a masterpiece of naval construction. Her removal eases our battleship situation, as we should have had to keep

King George V, Prince of Wales

, and the two

Nelsons

practically tied to Scapa Flow to guard against a sortie of

Bismarck

and

Tirpitz

, as they could choose their moment and we should have to allow for one of our ships refitting. Now it is a different story.”

†

After my talk with Captain Martin I remained on the bridge of the

Dorsetshire

for a while.

‡

When I asked if I could see the chart in the navigation room, permission was readily granted. Alone with my thoughts, I gazed for a moment at the mark showing where the

Bismarck

had gone down. Then I asked and was given Martin’s permission to visit our men in their quarters once every day and to concern myself with their wishes.

As Fähnrich (B) Stiegler later expressed it, after coming on board he had “for the first time stood defenseless in the presence of the enemy.” His thoughts were difficult to describe but were “different from those of his comrades, for, in contrast to them, he had already seen action in the Polish campaign.” After he was led below, the British must have noticed his Fähnrich’s piping, for a doctor whose

words the other survivors could not understand came to him. The German seamen called out, “Herr Fähnrich, they want to poison us with their injections. But we’re delighted to be saved and would like only a cigarette.” Stiegler played the interpreter and some of the men accepted the sedative injections. Then Stiegler grew weak. Soon he found himself back in an officer’s cabin, where he could bathe and sleep, and was given dry, warm clothes. He received his first meal from the ship’s midshipmen’s mess. Later, Captain Martin called him to the bridge. “What is the story on the dummy second stack you had?” he asked. But Stiegler could answer, “with a clear conscience,” that he had heard about it on board but had never seen it. He had performed his duty below deck and had not come on the upper deck until after the end of the action on 27 May.

“Why did you have to leave so many of our seamen behind?” Statz asked his interrogating officer shortly after coming on board the

Dorsetshire

. The latter replied, “Just be happy that you were rescued, we’ve picked up enough for interrogation.” Statz felt that “this interrogation officer was no seaman.” The British seamen had helped him undress and had brought him to a compartment in which several of his comrades were lying, covered with blankets. But then they had turned him out again, carefully, and signaled for him to come with them—Statz had no idea why—into the sick bay. They had noticed his wound and helped him onto the operating table, where the cut in his shoulder was sewn up.

Among the survivors was Maschinengefreiter Gerhard Lüttich. He had lost an arm and was so badly burned that none of us could understand how he managed to get aboard. He was being cared for in the ship’s sick bay, but he died on 28 May. The following day the ship’s chaplain officiated at the military rites accorded him and, after the firing of three salvos by an honor guard, his body was solemnly committed to the deep. In the late sixties, when I was consul general of the Federal Republic of Germany in Toronto, an extraordinary thing happened. I was approached at a social gathering by Philip Mathias, assistant editor of the

Financial Post

. Conveying friendly greetings from his father, Arthur, who, as master-at-arms in the

Dorsetshire

, was in charge of the prisoners of war, he handed me the identity tag that Arthur Mathias had removed from Lüttich’s dead body.

While the

Dorsetshire

and the

Maori

were steaming north, far to the south of us a dinghy was floating in the Atlantic. Its occupants

were three seamen, Herbert Manthey, Otto Höntzch, and Georg Herzog, who, towards the end of the firing, took cover behind turret Dora. Nearby they saw a rubber dinghy and, with the help of shipmates, dragged it behind the turret. Soon thereafter, as they stated later, they and the dinghy were washed overboard by the splash of a near miss. Although the dinghy floated away from them, they were able to reach it in about fifteen minutes and climb in. Very close by they saw a rubber raft with two men on it, one of them wounded, but they could not bring their drifting dinghy alongside and it was soon lost to sight. About the time the sun reached its zenith, they sighted a Focke-Wulf 200 Condor and tried to attract its attention by waving at it. Exhausted as they were, their hope of being rescued sank lower and lower as the day wore on until, around 1930, they became aware that there was a U-boat nearby.

As already recounted, Kapitänleutnant Kentrat in the

U-74

was alerted on the evening of 26 May to go to the assistance of the

Bismarck

. Between 0000 and 0400 the next day, he saw gunfire and star shells on the horizon. He tried to approach the

Bismarck

but, with a freshening wind and rising seas, it was very difficult for him to make any headway and waves constantly washing over his bridge made it virtually impossible for him to see what was going on. Around 0430, however, on the opposite side of the

Bismarck

, he saw the end-on silhouette of what he took to be a heavy cruiser or a battleship at a range of approximately 10,000 meters. He turned towards it, but visibility was so poor that he promptly lost sight of it. In his War Diary, he remarked: “It’s an abominable night. No torpedo could run through these swells.”

At about the same time as he sighted the silhouette, he heard three explosions, one of them particularly loud. Some two hours later, he made visual contact with Wohlfarth’s

U-556

and, as we already know, Wohlfarth transferred to him the mission of maintaining contact with the

Bismarck

. Around 0730, a cruiser and a destroyer suddenly emerged from a rain squall directly ahead of him at a range of 5,000 meters and he was forced to submerge. From 0900 on, Kentrat heard one explosion after another, but when he surfaced at 0922 there was nothing to be seen. At first, he assumed that what he was hearing was the scheduled Luftwaffe bomber attack. However, he wrote in his War Diary, “It must have been the

Bismarck’s

last battle.”

For 1200, the

U-74’s

War Diary contains the entry, “The pick-up of the

Bismarck’s

War Diary could not be carried out.” Thereafter, in

accordance with a radio directive from Commander in Chief, U-Boats, Kentrat began looking for survivors from the

Bismarck

. After about seven hours of searching, the

U-74

sighted three men in a rubber dinghy. With considerable difficulty because of high seas, Kentrat took them aboard. Scarcely had Herzog, Höntzsch, and Manthey gone down the hatch of the conning tower when an aircraft was seen to starboard. Kentrat waited until it had disappeared astern, before resuming his search. His objective was the spot where the

Bismarck

had gone down and, in order to be there at dawn on 28 May, he maintained a northerly course and traveled at low speed.

At about 0100 Kentrat’s men became aware of a strong smell of oil, and a couple of hours later the watch officer saw a red star below the horizon to the southeast. In the War Diary, Kentrat noted: “I was so exhausted I did not take in this report. A pity, perhaps we could still have saved a few comrades.” The

U-48

and the

U-73

joined the

U-74

to form a line of search but, other than oil fumes in the air, they found no trace of the

Bismarck’s

sinking. Kentrat thought he had missed the position where she sank. In the afternoon, however, he saw floating corpses and debris. He kept up his search for survivors until 2400, then headed for Lorient. His War Diary entry for 2400 on 28 May states:

The weather has abated, the seas are getting progressively calmer. As though nature were content with her work of destruction.

The 27 and 28 May will always be bitter memories for me. There we were, powerless, our hands tied, against the unleashed forces of nature. We could not help our brave

Bismarck

.

At Lorient, representatives of Group West awaited Herzog, Höntzsch, and Manthey. They were taken to Paris and there gave the first eyewitness account of the end of the

Bismarck

.

While the

U-74

was looking for survivors, the German weather ship

Sachsenwald

was doing the same thing to the south of her. On 27 May this ship, under the command of Leutnant zur See (S)

*

Wilhelm Schütte, was en route home after fifty days at sea. At 0200 that day she received a radio signal ordering her to proceed immediately to the

Bismarck’s

position. That meant steaming directly into the seas against a north-northwest wind of Force 6 or 7. At 0600, she was

ordered to stay where she was. Between 1100 and 1200 she sighted German planes and shortly after 1400 an order came to steer for another position. The weather was deteriorating. At 2010 a Bristol Blenheim that suddenly appeared to starboard fired at the

Sachsenwald

with her machine guns at a range of 11,000 meters, but did not hit her.