Battleship Bismarck (61 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

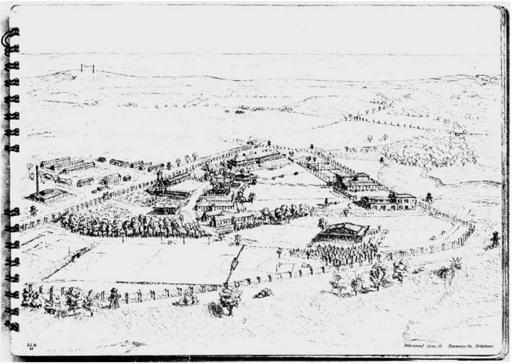

The first glimpse was highly agreeable. We saw pleasant, low houses and one or another higher, utilitarian structures, all built of solid stone, with pretty grounds planted in between with trees and shrubs. As a senior Kapitänleutnant—together with a Luftwaffe major—I enjoyed the advantage of being able to take possession of a double room in a long building. Besides a bed, we each had a table and, for the two of us, a separate bathroom with tub and sink, all centrally heated, and with hot water out of the tap. In fact, we were living in one of the teachers’ residences of a former country school of the Province of Ontario for handicapped boys, about sixty kilometers east of Toronto. The province had to put it at the disposal of the federal government in Ottawa after the previously defective accommodations of German prisoners had led to sharp exchanges between the German and Canadian governments and to threats of reprisals on the German side. I knew right away that I now found myself in a camp which later and quite justifiably came to be known as “unquestionably the finest on this or that side of the ocean.” And as long as I was a prisoner in Canada I would not voluntarily consent to being transferred to any other camp. The test of my resolution came quickly. A number of officers, among which I was included, were to be transferred to another camp in Ontario. I asked the German camp leadership to intervene with the Canadians on my behalf, as in the meanwhile I had been making progress in an academic course of instruction. The Canadians had no objections. Only the number of men transferred mattered. In such cases there were always volunteers.

Sketch of Prisoner-of-War Camp No. 30 at Bowmanville, Ontario, Canada, “unquestionably the finest camp on this or that side of the ocean.” (Photograph courtesy of Hans-Georg Stiegler.)

The truly comfortable accommodations—although for junior officers extremely cramped in interior space—were matched by the other camp facilities: reading and work rooms in the houses (later wooden barracks were built for classrooms); an auditorium for assemblies; a large gymnasium and beside it a heated swimming hall; a large kitchen next to the dining room; a dispensary; handball and volleyball courts, tennis courts that in winter were converted for ice hockey and figure-skating, football fields, a track, fields for gymnastics, medicine ball, etc.; land for laying out little gardens of vegetables or ornamental plants; a hothouse for tropical plants. In exchange for one’s word of honor not to escape, it was possible to take supervised walks outside the camp, to swim in nearby Lake Ontario and, in winter, to ski and toboggan. On their word of honor, those interested could also work on the adjacent camp farm. This produced extra potatoes, vegetables, and kitchen herbs. In the course of time, horses, cows, chickens, and pigs were also obtained. Inside the camp there was even a little zoo, consisting of two rhesus monkeys, three raccoons, a little crocodile, and two tame ravens and tortoises. The contents of the camp library were already imposing upon my arrival and increased significantly in the years to come.

Thus Bowmanville offered ample employment for mind and body and adequate freedom in the choice of activities.

The camp proper was enclosed by two barbed wire fences, each four meters high, with a knee-high warning wire on the inside. Outside stood tall watchtowers for the Canadian warders, the so-called Veteran Guards, who impressed us as older, calm and decent men. At night this security zone was illuminated by searchlights and ground lights and, understandably, as a rule we were not allowed to leave the houses.

At Bowmanville, as at Shap Wells, it was obligatory to make a presentation to the inmates of the camp on the circumstances in which one had been taken prisoner. As there were already about five hundred officers in camp, the number of listeners was substantial. When my turn came, before me there sat a representative part of our nation’s military bloodline, young men in the spring of life, navy, air force, and army officers, many of them daredevils, decorated, a few highly decorated—they all had been snatched out of the air, off the sea, or from the war on land in the years from 1939 to 1941.

We soon became accustomed to the daily routine of the camp. A

complete roll call was held at 0700 and 1800, and the meal times were at fixed hours. We ate in sections, as the dining hall would not seat everyone at once. The food was good, also in its variety, and abundant. Furthermore, we received a monthly allowance according to rank; for me as a Kapitänleutant it was $28.00, and later, as a Korvettenkapitän, $32.00. With this we could buy additional foodstuffs in the canteen and order personal articles and commodities of every sort, even such things as athletic equipment and lawn chairs from the mail-order catalog of the Eaton department store in Toronto. Rationed quantities of cigarettes and beer were also available. Naturally, the purchase of stronger alcohol was prohibited.

Our transfer to Canada could only confirm the suspicion I had harbored since Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union that the war would be a very long one. In any case, I wanted to use the time to come for a serious course of study and hoped to find an opportunity to do so in such a generously equipped camp as Bowmanville. It came soon and was due especially to the preliminary work of two men. On the

Rangitiki

Franz Schad, who has already been mentioned several times, had met another open-minded jurist: Dr. Walter Seeburg, a reserve major in the Luftwaffe, in civil life justice of the Hanseatic Provincial Court and deputy president of the Reich Higher Admiralty Court. Seeburg was a restrained but decided democrat—he and Schad had understood one another from the start. In many conversations below the barbed wire entanglement on the upper deck, walking back and forth near the ship’s bridge, they decided to start a program of study in the New World. From the experience in England they knew that passive resistance was to be expected from the German camp leadership, but this time, they resolved, they would overcome it. In Bowmanville this resistance was broken by a threat from Seeburg, the idea for which came from Schad: if necessary, Seeburg would denounce the anti-intellectualism in the officers’ camps in a letter to the state secretary in the Reich Ministry of Justice, Dr. Rothenberger, his former superior. This worked and the ice melted. The German camp leadership assigned a lecture room, as well as a library-workroom, to the two men for their course. The faculty of law was born.

On Ascension Day 1942 Franz Schad opened the Bowmanville law course with a lecture in a side room of the dining hall on the necessity and significance of the study of the history of law, which was also a prerequisite to understanding the various legal systems. I had enrolled as a student for the entire course in jurisprudence. While Schad

spoke, the dining hall rang with an “anti-intellectual” protest as plates and utensils were banged against one another. But such protests soon disappeared; people get used to anything.

While Seeburg was the “dean” of our faculty of law and Schad a founding lecturer, now it was necessary to recruit other teachers for the many-sided study of jurisprudence. They were found among the camp’s reserve and even, in part, regular officers; later accessions of prisoners brought increasing numbers of reserve officers, including lawyers. As lecturers there came into consideration especially officers who had qualified for the bench or the higher civil service. But those who had taken their first bar examination and had been appointed Assesoren (K)

*

during the war also in part proved to be outstanding lecturers. Gradually the program of instruction was broadened and deepened and it became possible to study almost every aspect of an ordinary law course. Lectures, study, exercises, seminars, examinations, and homework were all included in the methodology. In September 1942, the second semester at Bowmanville opened with more than forty students. Altogether, the studies there lasted six semesters, until the end of 1944, when transfers to other regions of Canada heralded the closing of the Bowmanville camp in April 1945.

There is no need to emphasize how important the supply of teaching materials was for these studies. It was, continually, acceptable to good. Law codes, textbooks, and commentaries were not only available but so abundant per capita that as a student at the University of Frankfurt-am-Main in the years 1947–49 I often thought longingly of the law library in Bowmanville. Specialized journals and Reich law statutes were also available. We owed this supply to the charitable and humanitarian organizations legitimatized by the Geneva Convention for the protection of prisoners of war, especially the International Educational Office, Geneva—Department for Mental Assistance to Prisoners of War, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the German and the Swiss Red Cross, the German Caritas Union, and the Young Men’s Christian Association. Here I think warmly and gratefully of the Director for Canada of the War Prisoners’ Aid of the Young Men’s Christian Association, the deceased Swiss citizen Hermann Boeschenstein. He frequently visited the

camp and occupied himself with the innumerable requests of the German prisoners. His activities were recognized in 1970 when, as consul general in Toronto, I presented him with the Grand Merit Cross of the Order of Merit which he had been awarded by the president of the Federal Republic.

Learning materials could also be acquired through private channels. In this connection hardly anyone was busier than the indefatigable Schad, who from the beginning of his captivity had made requests for literature from personal friends and from official sources in Germany and Switzerland and received it continuously. Engaged as he now was in research and teaching, he gradually accumulated seven hundredweight (350 kilograms) of professional publications in his baggage and was allowed to carry them along in his intermittent transfers from camp to camp, undisturbed by the British and Canadian authorities, although according to international agreement they were obliged to allow a total of only one hundredweight per officer. Oh yes, Schad and his books: when in 1946, coming from Canada with twenty-eight boxes from the last Canadian camp library in his baggage, he entered a British camp his comrades there greeted him with the words: “Oh no, here comes the Canuck, and he’s bringing twenty-eight boxes of democracy!” Unforgettable. But the British always had a soft spot for him. Upon his own repatriation, he left his store of books at the last camp in England. After it was closed the British government sent them to his home address in Württemberg, free of charge and postage paid!

One of the prerequisites for my admission to continue law studies at the University of Frankfurt-am-Main in April 1947 was proof of the six semesters of studies that I had completed at Bowmanville. The university gave me four semesters’ credit for them and, for the purpose of the first state law examination, certification of at least three consecutive semesters’ study in a German university. The credit for Bowmanville studies was optimal and I could be content. I took the first state law exam in Frankfurt in May 1949. Gratitude filled me then and fills me today to our teachers in Canada, who took it upon themselves to perform years of selfless labor to help those who were interested to prepare for the future. Very special thanks are due to program-founder Schad and to the memory of our Bowmanville “dean,” Dr. Walter Seeburg, who unfortunately died early.

The studies in Bowmanville gave me, a professional naval officer, the first direct insight into the devastation that Hitler had wrought and continued to wreak on the legal system in order to carry through

his dictatorship over our national life. This is an area about which a great deal has since been published and about which, writing from an autobiographical perspective, I can mention only a few points from my own experience. The course of study at Bowmanville began at a time when the Allied press was reporting a spectacular and apparently new attack by Hitler on the German judicature. The background lay in his speech to the “Greater German Reichstag”—which assembled for the last time on this occasion—in the Kroll Opera House in Berlin on 26 April 1942. At its end, the so-called Full Powers Act, later interpreted as the Supreme Enabling Act, proposed by Hermann Goring was “unanimously” accepted. Naturally, the details, text, or official significance of this law were not immediately available to prisoners of war in far-off Canada. As a rule, we could obtain so complete a picture only over a long period of time, often months, by various means: the Canadian radio, Allied news publications, secretly received radio broadcasts from Germany, the gradual receipt of statutes, specialized journals, and the like. And so now it was some time until we really understood this Reichstag session, about which the available extracts from Hitler’s speech had only shown his usual violent rhetoric and dark threats. What did it mean?

Among other things—I restrict myself to the field of law—Hitler had himself proclaimed “Supreme Magistrate,” and this “without being bound by existing legal formulas.” The public acceptance of the explanation he had given the Reichstag on 13 July 1934 after the murders in the Röhm affair,

*

in which he had said—“In this hour I was responsible for the destiny of the German nation and therefore the German people’s Supreme Magistrate”—no longer satisfied him; henceforth, he would no longer publicly need a spectacular, special motive to commit murder. From now on, therefore, murder at any time, murder enemies of the regime, critics of the regime, with or without the law—what was new about that, what was new about the long-established, absolute abrogation of the separation of powers?