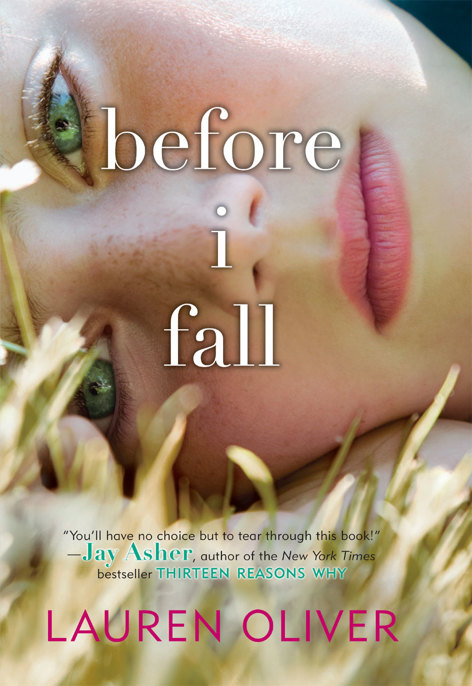

Before I Fall

Authors: Lauren Oliver

Tags: #Fiction, #Romance, #General, #Juvenile Fiction

Lauren Oliver

In loving memory of Semon Emil Knudsen II

Peter:

Thank you for giving me some of my greatest hits.

I miss you.

They say that just before you die your whole life…

“Beep, beep,” Lindsay calls out. A few weeks ago my…

In my dream I know I am falling though there…

In my dream I am falling forever through darkness.

Even before I’m awake, the alarm clock is in my…

You see, I was still looking for answers then. I…

This time, when I dream, there is sound. As I…

The last time I have the dream it goes like…

They say that just before you die your whole life…

They say that just before you die your whole life flashes before your eyes, but that’s not how it happened for me.

To be honest, I’d always thought the whole final-moment, mental life-scan thing sounded pretty awful. Some things are better left buried and forgotten, as my mom would say. I’d be happy to forget all of fifth grade, for example (the glasses-and-pink-braces period), and does anybody want to relive the first day of middle school? Add in all of the boring family vacations, pointless algebra classes, period cramps, and bad kisses I barely lived through the first time around…

The truth is, though, I wouldn’t have minded reliving my greatest hits: when Rob Cokran and I first hooked up in the middle of the dance floor at homecoming, so everyone saw and knew we were together; when Lindsay, Elody, Ally, and I got drunk and tried to make snow angels in May, leaving person-sized imprints in Ally’s lawn; my sweet-sixteen party, when we set out a hundred tea lights and danced on the table in the backyard; the time Lindsay and I pranked Clara Seuse on Halloween, got chased by the cops, and laughed so hard we

almost threw up—the things I wanted to remember; the things I wanted to be remembered for.

But before I died I didn’t think of Rob, or any other guy. I didn’t think of all the outrageous things I’d done with my friends. I didn’t even think of my family, or the way the morning light turns the walls in my bedroom the color of cream, or the way the azaleas outside my window smell in July, a mixture of honey and cinnamon.

Instead, I thought of Vicky Hallinan.

Specifically, I thought of the time in fourth grade when Lindsay announced in front of the whole gym class that she wouldn’t have Vicky on her dodgeball team. “She’s too fat,” Lindsay blurted out. “You could hit her with your eyes closed.” I wasn’t friends with Lindsay yet, but even then she had this way of saying things that made them hilarious, and I laughed along with everyone else while Vicky’s face turned as purple as the underside of a storm cloud.

That’s what I remembered in that before-death instant, when I was supposed to be having some big revelation about my past: the smell of varnish and the squeak of our sneakers on the polished floor; the tightness of my polyester shorts; the laughter echoing around the big, empty space like there were way more than twenty-five people in the gym.

And Vicky’s face.

The weird thing is that I hadn’t thought about that in forever. It was one of those memories I didn’t even know I remembered,

if you know what I mean. It’s not like Vicky was traumatized or anything. That’s just the kind of thing that kids do to each other. It’s no big deal. There’s always going to be a person laughing and somebody getting laughed at. It happens every day, in every school, in every town in America—probably in the world, for all I know. The whole point of growing up is learning to stay on the laughing side.

Vicky wasn’t very fat to begin with—she just had some baby weight on her face and stomach—and before high school she’d lost that and grown three inches. She even became friends with Lindsay. They played field hockey together and said hi in the halls. One time, our freshman year, Vicky brought it up at a party—we were all pretty tipsy—and we laughed and laughed, Vicky most of all, until her face turned almost as purple as it had all those years ago in the gym.

That was weird thing number one.

Even weirder than that was the fact that we’d all just been talking about it—how it would be just before you died, I mean. I don’t remember exactly how it came up, except that Elody was complaining that I always got shotgun and refusing to wear her seat belt. She kept leaning forward into the front seat to scroll through Lindsay’s iPod, even though I was supposed to have deejay privileges. I was trying to explain my “greatest hits” theory of death, and we were all picking out what those would be. Lindsay picked finding out that she got into Duke, obviously, and Ally—who was bitching about

the cold, as usual, and threatening to drop dead right there of pneumonia—participated long enough to say she wished she could relive her first hookup with Matt Wilde forever, which surprised no one. Lindsay and Elody were smoking, and freezing rain was coming in through the cracked-open windows. The road was narrow and winding, and on either side of us the dark, stripped branches of trees lashed back and forth, like the wind had set them dancing.

Elody put on “Splinter” by Fallacy to piss Ally off, maybe because she was sick of her whining. It was Ally’s song with Matt, who had dumped her in September. Ally called her a bitch and unbuckled her seat belt, leaning forward and trying to grab the iPod. Lindsay complained that someone was elbowing her in the neck. The cigarette dropped from her mouth and landed between her thighs. She started cursing and trying to brush the embers off the seat cushion and Elody and Ally were still fighting and I was trying to talk over them, reminding them all of the time we’d made snow angels in May. The tires skidded a little on the wet road, and the car was full of cigarette smoke, little wisps rising like phantoms in the air.

Then all of a sudden there was a flash of white in front of the car. Lindsay yelled something—words I couldn’t make out, something like

sit

or

shit

or

sight—

and suddenly the car was flipping off the road and into the black mouth of the woods. I heard a horrible, screeching sound—metal on metal, glass shattering, a car folding in two—and smelled fire. I had time

to wonder whether Lindsay had put her cigarette out.

Then Vicky Hallinan’s face came rising out of the past. I heard laughter echoing and rolling all around me, swelling into a scream.

Then nothing.

The thing is, you don’t get to know. It’s not like you wake up with a bad feeling in your stomach. You don’t see shadows where there shouldn’t be any. You don’t remember to tell your parents that you love them or—in my case—remember to say good-bye to them at all.

If you’re like me, you wake up seven minutes and forty-seven seconds before your best friend is supposed to be picking you up. You’re too busy worrying about how many roses you’re going to get on Cupid Day to do anything more than throw on your clothes, brush your teeth, and pray to God you left your makeup in the bottom of your messenger bag so you can do it in the car.

If you’re like me, your last day starts like this:

“Beep, beep,” Lindsay calls out. A few weeks ago my mom yelled at her for blasting her horn at six fifty-five every morning, and this is Lindsay’s solution.

“I’m coming!” I shout back, even though she can see me pushing out the front door, trying to put on my coat and wrestle my binder into my bag at the same time.

At the last second, my eight-year-old sister, Izzy, tugs at me.

“What?” I whirl around. She has little-sister radar for when I’m busy, late, or on the phone with my boyfriend. Those are always the times she chooses to bother me.

“You forgot your gloves,” she says, except it comes out: “You

forgot

your

gloveths

.” She refuses to go to speech therapy for her lisp, even though all the kids in her grade make fun of her. She says she likes the way she talks.

I take them from her. They’re cashmere and she’s probably gotten peanut butter on them. She’s always scooping around in jars of the stuff.

“What did I tell you, Izzy?” I say, poking her in the middle of the forehead. “Don’t touch my stuff.” She giggles like an

idiot and I have to hustle her inside while I shut the door. If it were up to her, she would follow me around all day like a dog.

By the time I make it out of the house, Lindsay’s leaning out the window of the Tank. That’s what we call her car, an enormous silver Range Rover. (Every time we drive around in it at least one person says, “That thing’s not a car, it’s a

truck

,” and Lindsay claims she could go head-to-head with an eighteen-wheeler and come out without a scratch.) She and Ally are the only two of us with cars that actually belong to them. Ally’s car is a tiny black Jetta that we named the Minime. I get to borrow my mom’s Accord sometimes; poor Elody has to make do with her father’s ancient tan Ford Taurus, which hardly runs anymore.

The air is still and freezing cold. The sky is a perfect, pale blue. The sun has just risen, weak and watery-looking, like it has just spilled itself over the horizon and is too lazy to clean itself up. It’s supposed to storm later, but you’d never know.

I get into the passenger seat. Lindsay’s already smoking and she gestures with the end of her cigarette to the Dunkin’ Donuts coffee she got for me.

“Bagels?” I say.

“In the back.”

“Sesame?”

“Obviously.” She looks me over once as she pulls out of my driveway. “Nice skirt.”

“You too.”

Lindsay tips her head, acknowledging the compliment. We’re actually wearing the same skirt. There are only two days of the year when Lindsay, Ally, Elody, and I deliberately dress the same: Pajama Day during Spirit Week, because we all bought cute matching sets at Victoria’s Secret last Christmas, and Cupid Day. We spent three hours at the mall arguing about whether to go for pink or red outfits—Lindsay hates pink; Ally lives in it—and we finally settled on black miniskirts and some red fur-trimmed tank tops we found in the clearance bin at Nordstrom.

Like I said, those are the only times we

deliberately

look alike. But the truth is that at my high school, Thomas Jefferson, everyone kind of looks the same. There’s no official uniform—it’s a public school—but you’ll see the same outfit of Seven jeans, gray New Balance sneakers, a white T-shirt, and a colored North Face fleece jacket on nine out of ten students. Even the guys and the girls dress the same, except our jeans are tighter and we have to blow out our hair every day. It’s Connecticut: being like the people around you is the whole point.

That’s not to say that our high school doesn’t have its freaks—it does—but even the freaks are freaky in the same way. The Eco-Geeks ride their bikes to school and wear clothing made of hemp and never wash their hair, like having dreadlocks will somehow help curb the emission of greenhouse gases. The Drama Queens carry big bottles of lemon tea and wear scarves even in summer and don’t talk in class because

they’re “conserving their voices.” The Math League members always have ten times more books than anyone else and actually still use their lockers and walk around with permanently nervous expressions, like they’re just waiting for somebody to yell, “Boo!”

I don’t mind it, actually. Sometimes Lindsay and I make plans to run away after graduation and crash in a loft in New York City with this tattoo artist her stepbrother knows, but secretly I like living in Ridgeview. It’s reassuring, if you know what I mean.

I lean forward, trying to apply mascara without gouging my eye out. Lindsay’s never been the most careful driver and has a tendency to jerk the wheel around, come to sudden stops, and then gun the engine.

“Patrick better send me a rose,” Lindsay says as she shoots through one stop sign and nearly breaks my neck slamming on the brakes at the next one. Patrick is Lindsay’s on-again, off-again boyfriend. They’ve broken up a record thirteen times since the start of the school year.

“I had to sit next to Rob while he filled out the request form,” I say, rolling my eyes. “It was like forced labor.”

Rob Cokran and I have been going out since October, but I’ve been in love with him since sixth grade, when he was too cool to talk to me. Rob was my first crush, or at least my first

real

crush. I did once kiss Kent McFuller in third grade, but that obviously doesn’t count since we’d just exchanged

dandelion rings and were pretending to be husband and wife.

“Last year I got twenty-two roses.” Lindsay flicks her cigarette butt out of the window and leans over for a slurp of coffee. “I’m going for twenty-five this year.”

Each year before Cupid Day the student council sets up a booth outside the gym. For two dollars each, you can buy your friends Valograms—roses with little notes attached to them—and then they get delivered by Cupids (usually freshman or sophomore girls trying to get in good with the upperclassmen) throughout the day.

“I’d be happy with fifteen,” I say. It’s a big deal how many roses you get. You can tell who’s popular and who isn’t by the number of roses they’re holding. It’s bad if you get under ten and humiliating if you don’t get more than five—it basically means that you’re either ugly or unknown. Probably both. Sometimes people scavenge for dropped roses to add to their bouquets, but you can always tell.

“So.” Lindsay shoots me a sideways glance. “Are you excited? The big day. Opening night.” She laughs. “No pun intended.”

I shrug and turn toward the window, watching my breath frost the pane. “It’s no big deal.” Rob’s parents are away this weekend, and a couple of weeks ago he asked me if I could spend the whole night at his house. I knew he was really asking if I wanted to have sex. We’ve gotten semi-close a few times, but it’s always been in the back of his dad’s BMW or in somebody’s

basement or in my den with my parents asleep upstairs, and it’s always felt wrong.

So when he asked me to stay the night, I said yes without thinking about it.

Lindsay squeals and hits her palm against the steering wheel. “No big deal? Are you kidding? My baby’s growing up.”

“Oh, please.” I feel heat creeping up my neck and know my skin’s probably going red and splotchy. It does this whenever I’m embarrassed. All the dermatologists, creams, and powders in Connecticut don’t help. When I was younger kids used to sing,

“What’s red and white and weird all over? Sam Kingston!”

I shake my head a little and rub the vapor off the window. Outside the world sparkles, like it’s been coated in varnish. “When did you and Patrick do it, anyway? Like three months ago?”

“Yeah, but we’ve been making up for lost time since then.” Lindsay rocks against her seat.

“Gross.”

“Don’t worry, kid. You’ll be fine.”

“Don’t call me kid.” This is one reason I’m happy I decided to have sex with Rob tonight: so Lindsay and Elody won’t make fun of me anymore. Thankfully, since Ally’s still a virgin it means I won’t be the very last one, either. Sometimes I feel like out of the four of us I’m always the one tagging along, just there for the ride. “I told you it was no big deal.”

“If you say so.”

Lindsay has made me nervous, so I count all the mailboxes

as we go by. I wonder if by tomorrow everything will look different to me; I wonder if I’ll look different to other people. I hope so.

We pull up to Elody’s house and before Lindsay can even honk, the front door swings open and Elody starts picking her way down the icy walkway, balancing on three-inch heels, like she can’t get out of her house fast enough.

“Nipply outside much?” Lindsay says when Elody slides into the car. As usual she’s wearing only a thin leather jacket, even though the weather report said the high would be in the mid-twenties.

“What’s the point of looking cute if you can’t show it off?” Elody shimmies her boobs and we crack up. It’s impossible to stay stressed when she’s around, and the knot in my stomach loosens.

Elody makes a clawing gesture with her hand and I pass her a coffee. We all take it the same way: large hazelnut, no sugar, extra cream.

“Watch where you’re sitting. You’ll squish the bagels.” Lindsay frowns into the rearview mirror.

“You know you want a piece of this.” Elody gives her butt a smack and we all laugh again.

“Save it for Muffin, you horn dog.”

Steve Dough is Elody’s latest victim. She calls him Muffin because of his last name, and because he’s yummy (

she

says; he looks too greasy for me, and he always smells like pot). They

have been hooking up for a month and a half now.

Elody’s the most experienced of any of us. She lost her virginity sophomore year and has already had sex with two different guys. She was the one who told me she was sore after the first couple of times she had sex, which made me ten times more nervous. It may sound crazy, but I never really thought of it as something physical, something that would make you sore, like soccer or horseback riding. I’m scared that I won’t know what to do, like when we used to play basketball in gym and I’d always forget who I was supposed to be guarding or when I should pass the ball and when I should dribble it.

“Mmm, Muffin.” Elody puts a hand on her stomach. “I’m starving.”

“There’s a bagel for you,” I say.

“Sesame?” Elody asks.

“Obviously,” Lindsay and I say at the same time. Lindsay winks at me.

Just before we get to school we roll down the windows and blast Mary J. Blige’s “No More Drama.” I close my eyes and think back to homecoming and my first kiss with Rob, when he pulled me toward him on the dance floor and suddenly my lips were on his and his tongue was sliding under my tongue and I could feel the heat from all the colored lights pressing down on me like a hand, and the music seemed to echo somewhere behind my ribs, making my heart flutter and skip in time. The cold air coming through the window makes my throat hurt and

the bass comes through the soles of my feet just like it did that night, when I thought I would never be happier; it goes all the way up to my head, making me dizzy, like the whole car is going to split apart from the sound.

POPULARITY: AN ANALYSIS

Popularity’s a weird thing. You can’t really define it, and it’s not cool to talk about it, but you know it when you see it. Like a lazy eye, or porn.

Lindsay’s gorgeous, but the rest of us aren’t that much prettier than anybody else. Here are my good traits: big green eyes, straight white teeth, high cheekbones, long legs. Here are my bad traits: a too-long nose, skin that gets blotchy when I’m nervous, a flat butt.

Becky DiFiore’s just as pretty as Lindsay, and I don’t think Becky even had a date to junior homecoming. Ally’s boobs are pretty big, but mine are borderline nonexistent (when Lindsay’s in a bad mood she calls me Samuel, not Sam or Samantha). And it’s not like we’re shiny perfect or our breath always smells like lilacs or something. Lindsay once had a burping contest with Jonah Sasnoff in the cafeteria and everyone applauded her. Sometimes Elody wears fuzzy yellow slippers to school. I once laughed so hard in social studies I spit up vanilla latte all over Jake Somers’s desk. A month later we made out in Lily Angler’s toolshed. (He was bad.)

The point is, we can do things like that. You know why?

Because we’re popular. And we’re popular because we can get away with everything. So it’s circular.

I guess what I’m saying is there’s no point in analyzing it. If you draw a circle, there will always be an inside and an outside, and unless you’re a total nut job, it’s pretty easy to see which is which. It’s just what happens.

I’m not going to lie, though. It’s nice that everything’s easy for us. It’s a good feeling knowing you can basically do whatever you want and there won’t be any consequences. When we get out of high school we’ll look back and know we did everything right, that we kissed the cutest boys and went to the best parties, got in just enough trouble, listened to our music too loud, smoked too many cigarettes, and drank too much and laughed too much and listened too little, or not at all. If high school were a game of poker, Lindsay, Ally, Elody, and I would be holding 80 percent of the cards.

And believe me: I

know

what it’s like to be on the other side. I was there for the first half of my life. The bottom of the bottom, lowest of the low. I know what it’s like to have to squabble and pick and fight over the leftovers.

So now I have first pick of everything. So what. That’s the way it is.

Nobody ever said life was fair.

We pull into the parking lot exactly ten minutes before first bell. Lindsay guns it toward the lower lot, where the faculty

spaces are, scattering a group of sophomore girls. I can see red and white lace dresses peeking out under their coats, and one of them is wearing a tiara. Cupids, definitely.

“Come on, come on, come on,” Lindsay mutters as we pull behind the gym. This is the only row in the lower lot not reserved for staff. We call it Senior Alley, even though Lindsay’s been parking here since junior year. It’s the VIP of parking at Jefferson, and if you miss out on a spot—there are only twenty of them—you have to park all the way in the upper lot, which is a full .22 miles from the main entrance. We checked one time, and now whenever we talk about it we have to use the exact distance. Like, “Do you really want to walk .22 miles in this rain?”