Before the Storm (77 page)

Authors: Rick Perlstein

Â

Within two weeks, the Administration was wracked by another crisis. This one, though, they were better prepared for.

Op Plan 34-A had rolled on through spring to no apparent military effect.

Dean Acheson cornered a new Johnson aide to tell him, “Things are going to hell in a hack in Vietnam, and if the President does not do something that relates to getting the support of Congress in a Formosa-type resolution”âthe blanket authority Eisenhower won from Congress to use military force if needed to protect Taiwan without declaring warâ“it's going to be too late, and we'll go into this orgasm of a campaign period in which things will just have to stall.” Johnson's men, reasoning they had to begin countering criticisms that Johnson was holding back in Vietnam because of the upcoming election, decided that proceeding with Acheson's suggestion wasn't such a bad idea. On May 22, with their boss away delivering a commencement address at the University of Michigan, they began to work on a draft.

Dean Acheson cornered a new Johnson aide to tell him, “Things are going to hell in a hack in Vietnam, and if the President does not do something that relates to getting the support of Congress in a Formosa-type resolution”âthe blanket authority Eisenhower won from Congress to use military force if needed to protect Taiwan without declaring warâ“it's going to be too late, and we'll go into this orgasm of a campaign period in which things will just have to stall.” Johnson's men, reasoning they had to begin countering criticisms that Johnson was holding back in Vietnam because of the upcoming election, decided that proceeding with Acheson's suggestion wasn't such a bad idea. On May 22, with their boss away delivering a commencement address at the University of Michigan, they began to work on a draft.

When the first U.S. reconnaissance planes were downed during the Cleveland governors' conference in early June, William Bundy and Dean Rusk advised the President that they should begin polishing up the draft. Senate leader Mike Mansfieldâcoincidentally, for he knew nothing of any potential congressional resolutionâgave similar advice: “If we're gonna stay in there, we're gonna have to educate the people, Mr. President.” Mr. President's mind being on poll numbers showing that 63 percent of Americans were paying no attention to Vietnam, his answer to both was that he had no interest in making Vietnam an issue as the campaign approached, especially now with civil rights on the cusp of passage. But he was flexible. When GOP congressmen began chorusing against a “no-win” Vietnam policy in late June, Johnson obligingly dispatched hundreds more “military advisors.” He balanced that move by coining an artful new phrase for public consumption: “We seek no wider war.” The coinage left him euphoric.

When the senator from Arizona's nomination became imminent, Bill Moyers urged his boss to talk tough about Vietnam on TV to “defuse a Goldwater bomb before he ever gets the chance to throw it.” Once more, Johnson demurred. As the rubble was being cleared in the streets of Harlem, he ordered secret maneuvers in the Gulf of Tonkin stepped up. The CIA assured him that would be enough to hold the line until after the election was over. The idea that North Vietnamese PT boats might challenge U.S. warships seemed too incredible to consider. Although Communist insurgents thought otherwise. They embraced the heightened American presence in the Gulf as a chance to signal their determination to fight the imperialists to the death.

On August 2, three PT boats advanced on the destroyer

Maddox.

Her captain retreated languidly out to sea. He was startled to see the scrappy little boats scooting out after himâthen, twenty-five miles farther out, opening fire. Jets from a nearby aircraft carrier and the

Maddox's

5-inch guns made short work of

these fleas, the Maddox emerging none the worse for the wear. It was around three in the afternoon local time, August 2â3 a.m., August I, in Washingtonâwhen the crisis report was brought to the President's bedside. He saw not much in the incident, sending Hanoi a perfunctory diplomatic note warning that “grave consequences would inevitably result from any further unprovoked offensive military action” and ordering a second carrier and destroyer to the area to put such foolish displays of enemy bravado to a stop. The clash certainly wasn't enough to distract him from more important matters. “Raymond Guest wants to contribute to you but he still wants to be ambassador to Ireland,” Florida senator George Smathers told him later in the morning. Johnson laughed and asked how much Guest was willing to pay. “Well, he'll contribute fifty. Maybe you can get more.” LBJ: “He oughta give a hun'red thousand, as much as that fella's worth.” Smathers: “Well, if he can get it, I can get a hundred thousand.”

Maddox.

Her captain retreated languidly out to sea. He was startled to see the scrappy little boats scooting out after himâthen, twenty-five miles farther out, opening fire. Jets from a nearby aircraft carrier and the

Maddox's

5-inch guns made short work of

these fleas, the Maddox emerging none the worse for the wear. It was around three in the afternoon local time, August 2â3 a.m., August I, in Washingtonâwhen the crisis report was brought to the President's bedside. He saw not much in the incident, sending Hanoi a perfunctory diplomatic note warning that “grave consequences would inevitably result from any further unprovoked offensive military action” and ordering a second carrier and destroyer to the area to put such foolish displays of enemy bravado to a stop. The clash certainly wasn't enough to distract him from more important matters. “Raymond Guest wants to contribute to you but he still wants to be ambassador to Ireland,” Florida senator George Smathers told him later in the morning. Johnson laughed and asked how much Guest was willing to pay. “Well, he'll contribute fifty. Maybe you can get more.” LBJ: “He oughta give a hun'red thousand, as much as that fella's worth.” Smathers: “Well, if he can get it, I can get a hundred thousand.”

There followed a misunderstanding worthy of

Strangelove.

What Johnson thought was a stalling maneuver his field commanders thought was an answer to their long-stated recommendation to turn the Vietnam affair into a real fight. Admirals sent their shipsâtwo carriers and two destroyers, sailing on instruments in the middle of a vicious stormâinto the Gulf with orders to regard any vessel they encountered “as belligerents from first detection.” Suspicious bleeps showed up on the

Maddox's

sonarâwhat appeared to be twenty-two torpedoes heading straight at them. At 9 p.m. the sailors set their guns ablazing, then flashed news of a North Vietnamese attack to Washington.

Strangelove.

What Johnson thought was a stalling maneuver his field commanders thought was an answer to their long-stated recommendation to turn the Vietnam affair into a real fight. Admirals sent their shipsâtwo carriers and two destroyers, sailing on instruments in the middle of a vicious stormâinto the Gulf with orders to regard any vessel they encountered “as belligerents from first detection.” Suspicious bleeps showed up on the

Maddox's

sonarâwhat appeared to be twenty-two torpedoes heading straight at them. At 9 p.m. the sailors set their guns ablazing, then flashed news of a North Vietnamese attack to Washington.

Forty-five minutes later the President was on the phone with an old Texas pal, former Eisenhower treasury secretary Robert Anderson. Anderson was in charge of one of Johnson's pet campaign projectsâswaying Republican tycoons into the Johnson column. Presuming that the President was on the phone to talk about campaign matters, Anderson rattled off the names of the esteemed executives he was lining upâincluding, extraordinarily, the CEO of Borg-Warner, the auto-parts empire that once belonged to Peggy Goldwater's family. Anderson brought up the name of a businessman he knewâthe mobbed-up proprietor of a scandal sheet called the

National Enquirerâwho

wanted to donate $250,000 to Johnson's favorite charity, the Sam Rayburn Foundation, and kick in a few thousand more to the campaign. The wealthy contributor was currently being inconvenienced by a Justice Department investigation of a merger in which he had an interest, Anderson explained. Johnson promised to make a few calls and see what he could do to help him out.

National Enquirerâwho

wanted to donate $250,000 to Johnson's favorite charity, the Sam Rayburn Foundation, and kick in a few thousand more to the campaign. The wealthy contributor was currently being inconvenienced by a Justice Department investigation of a merger in which he had an interest, Anderson explained. Johnson promised to make a few calls and see what he could do to help him out.

Then the President abruptly changed the subject. He told his friend about Op Plan 34-A and the retaliation it had brought on. “Make it look like a very

firm stand,” was Anderson's advice. “You're gonna be running against a man who's a wild man,” who would surely say that if it were up to him, he “would have knocked 'em off the moon.”

firm stand,” was Anderson's advice. “You're gonna be running against a man who's a wild man,” who would surely say that if it were up to him, he “would have knocked 'em off the moon.”

Johnson rang Bob McNamara. He explained that in their briefing of congressional leaders later in the day they had to “leave an impression ... that we're gonna be firm as hell”âlest Goldwater “[raise] hell about how he's gonna blow 'em off the moon.”

More storms. Three hours later the guns fell silent and the Maddox's captain wired warning that what they thought were enemy attacks might well have been sonar anomalies created by freak weather effects. Johnson's meeting with congressional leaders was fast approaching. So were deadlines for the morning papers. The President was in no mood for ambiguity. “Some of our boys are floating in the water,” he lied to the sixteen congressional leaders who had filed into the Cabinet Room.

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was approved within the week with only two dissenting votes. Hubert Humphrey helped tip the scales by conjuring up visions of General Walker and Curtis LeMay. “There are people in the Pentagon,” he said, “who think we ought to send three hundred thousand troops over there.” None of the congressmen were aware of Op Plan 34-A; they thought they were voting to avenge a vicious, unprovoked attack. The resolution was the sole congressional authorization for a decade of undeclared war in Vietnam.

The strikes were launched. Speechwriters prepared an address to the nation. Somewhat reluctantly, LBJ tried to reach Barry Goldwater, who was on a boat somewhere off Newport Beach, where he was vacationing instead of in Germany. Goldwater called back from the dock, his patriotic instincts kicking in, pleased that Johnson was finally doing what he had hoped forâturning the problem over to the military. He assured his President of his total support: “We're all Americans and Americans stick together.” Johnson sighed with relief.

Still, Johnson found the political risk in the speech excruciating. “We don't

have

to make it, do we?” he pleaded with McNamara, who assured him that they did. The President waited until strikes were under way to speak. “We Americans know, although others appear to forget”âa reference to Goldwaterâ“ the risk of spreading conflict. We seek no wider war.”

have

to make it, do we?” he pleaded with McNamara, who assured him that they did. The President waited until strikes were under way to speak. “We Americans know, although others appear to forget”âa reference to Goldwaterâ“ the risk of spreading conflict. We seek no wider war.”

The Gulf of Tonkin affair, he now understood, was a blessing in disguise. With the patriotic Goldwater uneager to challenge him on Vietnam, it would only become a campaign issue if Johnson made it oneâon his own terms.

Â

Racial politics was not nearly so amenable to control. Like Richard Nixon in 1960, Johnson was busy writing the script for his own coronationâthe Democratic

National Convention, which was to open on August 24. And, like Nixon's, the coronation threatened to become a war. The problem wasn't Barry Goldwater. It was a Mississippi farmhand named Fannie Lou Hamer and her Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

National Convention, which was to open on August 24. And, like Nixon's, the coronation threatened to become a war. The problem wasn't Barry Goldwater. It was a Mississippi farmhand named Fannie Lou Hamer and her Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Richard Nixon's chances of winning the nominationwere taken very seriouslyâthough the behind-the-scenes conniving of a candidate many considered a pathetic has-been left some, including

The Washington Post's

cartoonistHerblock, disgusted.

The Washington Post's

cartoonistHerblock, disgusted.

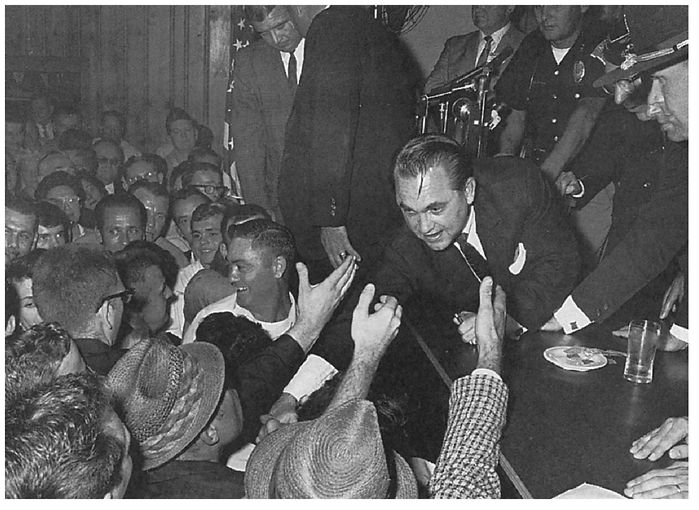

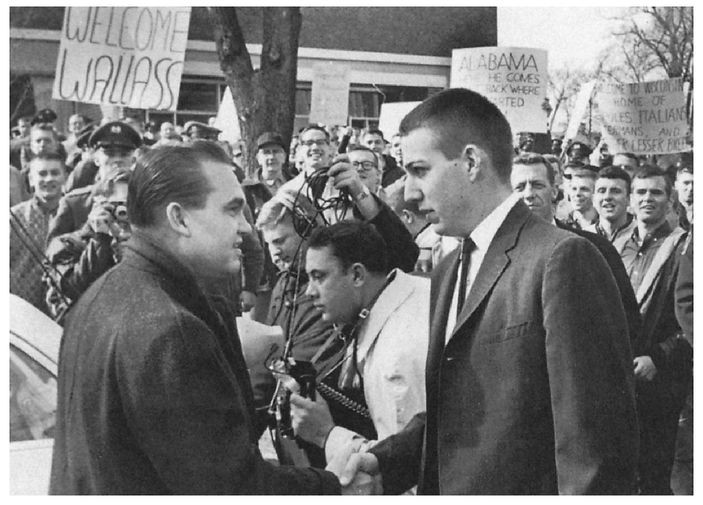

George Wallace's anti-civil rights run in three Democratic primaries thrilled many working-classwhite voters (above), while others were less than openly supportive (below). Everyone exceptWallace was stunned by the Alabaman's relative success in the three races, and the word “backlash” soon dominated coverage of the presidential race.

Other books

Summer I Found You by Jolene Perry

Test Drive by Marie Harte

Aethosphere Chronicles: Winds of Duty by Jeremiah D. Schmidt

The Gardener's Son by Cormac McCarthy

Private Novelist by Nell Zink

A Collector of Hearts by Sally Quilford

Dark Tendrils by Claude Lalumiere

JF01 - Blood Eagle by Craig Russell

The Reaping (The Reapers Book 1) by Katharine Sadler

Curtain Call by Anthony Quinn