Behind the Shock Machine (21 page)

Read Behind the Shock Machine Online

Authors: Gina Perry

Milgram replied two days later, telling the man: “This experimental research is being supported by the Federal Government, and officially, I am not supposed to talk about its true purposes.” But Milgram offered to discuss it with him if he could keep the information “confidential.”

3

Six months later, another of Milgram’s subjects wrote to say that he had picked up on the deception. A letter dated February 12, 1962, was from a subject who took part in a condition that involved three teachers, two of whom were confederates. The experimenter was called away during the proceedings by a rigged phone call. The man described the arrival of the third volunteer before the experiment began and how, when the group of them got to a doorway, the others stood aside to let him go first. This “red carpet” treatment made him suspicious, as did the drawing of lots for roles. He continued:

As Mr. Wallace was being secured in the “electric chair,” his remark of having a “bad heart” and a history of hospitalization for it had practically no effect upon the “assistant” in charge. He dismissed the complaint with, “This machine has been tested and does no tissue damage.” This, of course, had nothing to do with the complaint.

The learner was strapped into the chair and the three teachers were given their allotted roles: the first, reading the word pairs; the second, giving shocks; and the third, reading out the correct answers. The author

of the letter wondered why Yale would pay three people for a job that could be done by one. When the experimenter got an emergency phone call and had to leave, he knew that the experiment was a setup. “All my doubts were now confirmed—I was the one being tested!”

At that point, the learner began to give the wrong answers, and the subject had to administer the shocks. At some point he disobeyed, and one of the other teachers said that he would take over:

When “Mr. Barnaby,” very unconcerned, took over as “executioner” and continued until the “learner” was beyond replying, the experiment ended and the “assistant” showed up at the exact appropriate moment.

I now was certain that I had “been had.” I gave the “assistant” the expected answers, the “heart victim” emerged smiling, and I was dismissed.

At this point I expected someone to say, “You have been on

Candid Camera

, and I am Dorothy Collins in disguise.”

The hour was late, I had a previous appointment, so I left feeling that the three remaining conspirators were feeling as pleased with themselves as I was with myself for having seen through such an obvious test of conformity.

I hope I have been some assistance to you, and thereby earned my $4.50.

4

Milgram always maintained that his subjects believed what he wanted them to believe. But it’s clear that some subjects had their own views of what had happened.

Many subjects also expressed their suspicions in the questionnaire they returned to Milgram in the summer of 1962. These skeptical volunteers spanned the full range of conditions, indicating that the authenticity of the experiment didn’t improve over time. A sample from conditions 4 to 18 includes Subject 408—“I found it hard to believe that Yale would allow a paid subject (the actor) to absorb such punishment. The description on the control board was a bit far fetched (i.e. strong shock etc) . . . the learner’s poor answers were not completely believable. He seemed too intelligent to stumble so”—and Subject 502: “I offered the shock recipient the opportunity to

avenge himself on me by letting him give me the works. His refusal convinced me that he was an experimenter or an unshocked participant.” Subject 722 noted, “I was of the opinion that everything was rigged and we were puppets. I did not believe that the learner was being hurt in any way,” while Subject 1914 wrote, “I felt fairly sure that I was the only subject, and my own reactions were being studied rather than the ‘students.’ Because of this I did continue with the program, almost feeling a gleeful pleasure at having guessed, in some degree, what was actually happening.” And Subject 929, rather self-congratulatory, wrote: “I caught the one way glass right away and also the ‘dog eared’ check handed to one of your actors. I felt I had the whole operation doped out and told your Dr. Williams so. I think I was very observant and pat myself on the back for being so sharp.”

5

Some cover stories were so puzzlingly elaborate that it’s easy to see why subjects doubted them. Condition 18, for example, involved Williams saying that he had an urgent phone call and had to leave, asking the subject to conduct the experiment in his absence and leaving a phone number where he could be reached. If the subject rang to ask Williams what to do, he was given the standard prompts to continue. As one man described it, the fact that the experimenter left the subject in charge of something so seemingly important was a sign of something fishy: “Another thing that made me feel it was rigged was the fact that on an experiment where somebody would be asked to devote their time to come down to do something like this [the experimenter] was going to leave and wouldn’t be back for an hour. . . . That, coupled with the bad heart . . . and the mirror and [the fact that] I thought that we were being observed.” Another commented, “I think that something as important as that the professor wouldn’t have gone away.”

Others were alert to the phoniness of the experimental props. Subject 508 noted, “When the professor gave me the nod to go ahead, the thought went through my mind that that sounds like a recording. That’s when I first realized that it was rigged and from that moment on it didn’t make a bit of difference to me.”

6

Subject 1810 also noticed anomalies in the setting. He told Errera

“there were things about this setup that didn’t seem quite true.” He noticed when Williams was strapping McDonough that there was a loudspeaker in “the upper right-hand corner of the room,” and when McDonough started yelling, “[I] didn’t hear him through the hole in the door, which I should have; I heard him up to the right-hand side.” He said he thought a tape recorder was hooked up to the speaker, and “it put a doubt in my mind.” When the learner shouted out that he refused to continue, he phoned the experimenter from the lab, and “I thought I heard the telephone ring on the other side of the . . . two-way mirror and I was quite sure that the telephone I rang was just inside the glass . . . these are some of the things that keep going around in my head and [I was] trying to determine was this thing really true, was it happening?” He explained, “I was really searching for some—just a clue—of whether he was there or not, and I knew that his hands were strapped in. I asked him to kick the wall, and I received no response. Even being a cinder-block wall, I should have been able to hear it.” He regretted his passivity, telling Errera, “I should have stopped or I should have had a look in the other room. I wasn’t sure if it was a hoax.”

7

Yet even if he’d wanted to check on the learner, he wouldn’t have been able to. Another man who took part in the same condition was present at another Errera-conducted interview, and he explained that when Williams left him to continue the experiment on his own, Williams had unscrewed the knob on the door to the learner’s room and taken it away with him.

8

One of the most powerful causes for skepticism was the learner’s agreement to take part, given his apparent heart condition. One man told Errera, “Well, look at it the other way now . . . this man said he had a heart attack and just came out of the hospital . . . I’m sure that if any person had had a heart attack he would not have said, ‘Well, all right, go ahead, I got nothing to lose,’ and I can’t conceive of the instructor telling us to go ahead and keep shocking this man.” Another subject confessed, “When he said that he had a bad heart, I felt then that it was rigged because I felt that Yale would not be responsible if somebody was going to have the electricity shock treatment . . . that they would have made sure that he would have had a physical

examination. In other words, they wouldn’t just pull someone in off the street.” A third said, “I had my suspicion as to his authenticity when he went along with the experiment in spite of a supposed weak heart. . . . My suspicions were affirmed when I said I was giving him a higher voltage shock when actually I pressed the lowest voltage button and his cries still increased.”

9

The confusing mix of signals subjects were getting—that the learner was in pain, that the experimenter wouldn’t allow them to hurt anyone, that the machine gave real shocks, disbelief that this could be happening at Yale—left many subjects in a state of uncertainty and stress. It was not a simple case of a conflict between conscience and the experimenters’ commands. Subject 919 described this situation colorfully in a conversation with Errera.

Subject 919: I was sort of torn between two thoughts. One was that I was a patsy amongst a bunch of shills and the other was that this possibly was a legitimate experiment.

Errera: You’d better translate for me. What’s a patsy amongst shills?

Subject 919: A patsy is a pigeon, that’s what I say.

Errera: And a shill is—

Subject 919: More or less a professional pigeon . . . who gets the game going for the house.

10

This process of seesawing between what to believe, what to disregard, and whether the experiment was on the level intensified the stress of an already stressful situation. Milgram’s subjects were facing two incongruous pieces of information: the learner’s pain and the experimenter’s lack of concern for this pain. As Ian Parker put it, the choice was between “a man in apparent danger and another man—a man in a lab coat—whose lack of evident concern suggested there was no danger.”

11

So who did the subject believe? Psychiatrists Martin Orne and

Charles Holland argued that Milgram’s subjects, upon being faced with such a puzzling inconsistency, understood unconsciously that no harm was being done. Based on this theory, if a subject instinctively believed the experimenter, they obeyed. If they did believe the learner to be in danger, they disobeyed.

12

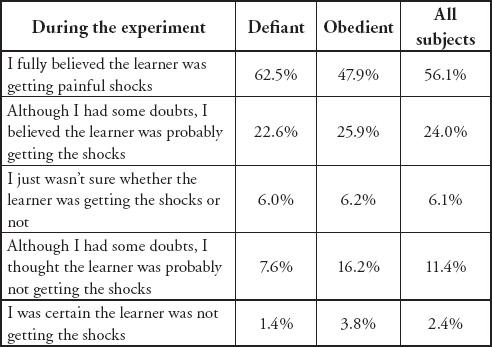

This theory turns Milgram’s results upside down. If people’s suspicions affected their behavior, their obedience could have been a sign that they believed there was no danger involved—that at some level, they’d seen through the ruse. Reading this prompted me to seek out this table from Milgram’s

Obedience to Authority

.

Milgram argued that three-quarters of his subjects “by their own testimony acted under the belief that they were administering painful shocks.” I looked at the numbers again. Milgram’s three-quarters looked more like half to me. In his conclusion that more than 75 percent of his subjects believed the learner was receiving painful shocks, he had included the 24 percent who had some doubts over whether what was happening was real. It’s more truthful to say that only half of the people who undertook the experiment fully believed it was real, and of those two-thirds disobeyed the experimenter.

Milgram would later argue that this was a case of subjects denying the disturbing fact of what they had done by pretending in retrospect that they had never believed it. Just as he did with people who disagreed with his results, Milgram dismissed criticism as an inability to face a particularly troubling truth.

13

At the same time, Milgram was obviously sufficiently worried about the number of people who wrote in the questionnaires that they had seen through the experiment. Late one afternoon in the archives, I found a more detailed analysis of just how many of Milgram’s subjects had gone to the maximum voltage—been “obedient”—because they suspected that the experiment was a hoax. Milgram had asked Taketo Murata, his research assistant in the summer of 1962, to compile a condition-by-condition breakdown of the number of people who said that they doubted the learner was getting shocked. He was then supposed to compare that with the degree of shock they actually gave.

Taketo divided the subjects into two groups. One contained those who were certain the learner was being shocked; the other, those who said they had doubts. Taketo found that in eighteen of twenty-three conditions, those who wrote that they fully believed the learner was receiving painful shocks gave lower levels of shock than those who said they thought that the learner was faking it.

Taketo’s unpublished analysis, suggesting that many went to the maximum voltage because they knew they weren’t torturing anybody, contradicted Milgram’s claims. In all twenty-three variations of the experiment, Taketo found the people most likely to disobey and give lower-voltage shocks were those who said they believed someone really was being hurt.

14

Depending on which piece of data you look at—Milgram’s published table or Taketo’s unpublished analysis—you could be forgiven for coming to completely different conclusions.