Belching Out the Devil (2 page)

Read Belching Out the Devil Online

Authors: Mark Thomas

Â

Back in 2001 I was writing a column for the

New Statesman

magazine, a left-of-centre weekly with circulation figures that were the envy of every other British left-wing journal. It is sold in many cities and was once spotted in a petrol station rack. It is a crotchety old rag that is owned by a New Labour millionaire, runs adverts for the arms dealers BAE Systems and gives out Tesco gift vouchers as prizes for its competitions, but somehow it manages to host really good columnists from John Pilger to Shazia Mirza. I loved working for it and after one

column was left a message from a chap called Professor Eric Herring, offering to help me by providing academic research and data. After the initial shock of realising that some academics have social skills and can conduct a conversation without the need for footnotes and peer review, a world of wonderfully brainy folk opened up to me. It is not that the academic world is closed to outsiders it is just insular, very insular. So it is essential to have a guide through this world, someone like Professor Eric Herring. If he was unable to help with an issue he would invariably pass me on to another academic who could. It was like Mensa meets the Masons but without the aprons and David Icke pointing the finger

New Statesman

magazine, a left-of-centre weekly with circulation figures that were the envy of every other British left-wing journal. It is sold in many cities and was once spotted in a petrol station rack. It is a crotchety old rag that is owned by a New Labour millionaire, runs adverts for the arms dealers BAE Systems and gives out Tesco gift vouchers as prizes for its competitions, but somehow it manages to host really good columnists from John Pilger to Shazia Mirza. I loved working for it and after one

column was left a message from a chap called Professor Eric Herring, offering to help me by providing academic research and data. After the initial shock of realising that some academics have social skills and can conduct a conversation without the need for footnotes and peer review, a world of wonderfully brainy folk opened up to me. It is not that the academic world is closed to outsiders it is just insular, very insular. So it is essential to have a guide through this world, someone like Professor Eric Herring. If he was unable to help with an issue he would invariably pass me on to another academic who could. It was like Mensa meets the Masons but without the aprons and David Icke pointing the finger

Â

One day Professor Eric Herring left a message saying, âReally good column, nice analysis but you need up-to-date examples, you need to talk to Doug, one of my research students. He'll tell you about Colombia.' And what he told me about Colombia was the shocking figures and facts about the number of trade union organisers and leaders killed by paramilitary death squads. Thousands killed for the audacity of challenging sackings, wage cuts, intimidation, coercion to work longer hours, unsafe conditions and trying to halt the wave of casualised jobs - temporary jobs with no security or protection - that has swept over Colombia.

Â

As one of the academics was connected to the Colombia Solidarity Campaign it was only a matter of time before I came into contact with them and their campaign on Coca-Cola, as trade union leaders working for the Coke bottlers had been killed by death squads: one of those was killed inside the bottling plant.

Â

Misfortunes seemed to rain upon the Company around this time. Coca-Cola were getting some considerable attention on

the issue of obesity from the Parliamentary Select Committee on Health

2

and the story of Plachimada in Kerala hit the international airwaves after the Coca-Cola bottlers there faced massive protests accusing the Company of exploiting the communal water resources. So depleted was the water supply that the Company was forced to bus in two tankers of water a day for the villagers.

3

the issue of obesity from the Parliamentary Select Committee on Health

2

and the story of Plachimada in Kerala hit the international airwaves after the Coca-Cola bottlers there faced massive protests accusing the Company of exploiting the communal water resources. So depleted was the water supply that the Company was forced to bus in two tankers of water a day for the villagers.

3

Â

Then one afternoon I was talking to the man who used to produce my TV work, Geoff Atkinson. He is a quirky British chap, a large man with curly blond hair and a habit of wiggling his thumbs to signify excitement and contentment. In effect he has shrugged off years of evolution and relegated his prehensile thumb to the role of a dog's tail. Geoff was drinking a bottle of Coca-Cola and as we started to discuss New Labour I had pointed at the bottle and said , âThat is New Labour. Good packaging, lots of sugar and otherwise worthless.' Half an hour later I had formalised my obsession with the Company. There followed two months of internet trawls, late-night phone calls to anyone who was still awake and long meetings with non-governmental organisations and journalists, all of which culminated at the start of 2004 with me standing outside the Coke bottling plant in Southern India clutching a borrowed camera from Geoff pondering the subjects of globalisation, democracy, and wet wipes.

Â

Over the next year I wrote and toured a stage show about the company, had numerous columns about Coke in the

New Statesman

(to the extent of the editor telling me âYou really can't do them three weeks running') and I co-curated an exhibition, with artist and friend Tracey Moberly, that invited anyone to submit drawings, pictures and Photoshopped images mocking the company's adverts.

New Statesman

(to the extent of the editor telling me âYou really can't do them three weeks running') and I co-curated an exhibition, with artist and friend Tracey Moberly, that invited anyone to submit drawings, pictures and Photoshopped images mocking the company's adverts.

All of us have psychological ticks and mine is that I find enemies easier to work with than friends. Broadly speaking you know where you are with an enemy and there is always the faint possibility of redemption; friends are altogether more complex and require much more attention. In the voyeuristic car-crash TV world of agony aunts and life coaches we are often told of the value of âmoving on', of walking away from trouble and getting on with our lives. But there is little joy to be had in avoiding trouble and people who don't bear grudges frankly have not got the emotional stamina for the job.

Â

Friends who still wanted to speak to me asked, âWhy Coca-Cola, why are you going after them?' And the answer I most frequently gave was that The Coca-Cola Company is a relatively small company that makes syrup - they don't actually make much pop themselves. They franchise out the pop production, getting other companies to make it. Admittedly they own some of those companies, they have major shareholdings in others and some are what are called âindependent bottlers' -but they are all franchisees. They operate under what the company calls âthe Coca-Cola system'. The Coca-Cola Company (or TCCC) controls who gets the franchise, they control the distribution of concentrate (the syrup with which to make Coke), the production method, the packaging and they even coordinate marketing and advertising with the local bottlers. They have an enormous level of control over the bottlers yet will often claim they have no legal or moral responsibility for the actions of their bottlers if it involves labour rights or environmental abuses.

Â

The one thing The Coca-Cola Company does have is a whopping great enormous brand and that is what they sell. Coke epitomises globalisation: a transnational worth billions that actually produces very little and yet is known the world over.

And that is truly part of the reason. But it is not the whole answer. There are two other reasons why I wanted to look at Coca-Cola and the first is simple: I don't like Pepsi. I never have and I never will. Coca-Cola is what I used to drink every day and, like many everyday things, I never really questioned it. In a similar way, I look at my watch but I have never wondered who first quantified units of time. Then one day sitting with Geoff I just looked at the bottle and thought, âWhat actually is it I am drinking?' And I wasn't looking at just the physical ingredients, but the ingredients of the brand and the company. Like many, I did not buy South Africa goods while Mandela was jailed, as they were contaminated by the apartheid system; so what battles were going on in a bottle of Coke? I just wanted to know - and considering that every year they spend billions of dollars on advertising, I reckon a few of those dollars were spent on me. As far as I'm concerned they came after my custom, so they started it.

Â

The first reason is specific to me; the second is global. When George Mallory was asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest he said âBecause it's there.' Why do I want to write about Coke? âBecause it's everywhere.' You can't escape it.

Â

And sitting here in Atlanta airport the impact of that statement was just beginning to hit me. The gulf between self-image and reality can be an ego-crushing chasm. I like to think I have a competent grasp of the basic concepts of globalisation, human rights and social movements, but realistically I know on a bad day I'm about as incisive and cutting as a Haribo.

Â

Like most big-heads I believe my abilities to be greater than they are, but even I have moments of clarity. This morning I

visited the Coke museum which is a testimony to the Company's history and its advertising blitzkriegs, and as I look around I realise I am witnessing a skirmish in one of those battles right now. In the immediate vicinity of my seat in the the airport lounge is a man-sized Coca-Cola fridge packed with Company products, an authentic Mexican diner serving drinks in Coke glasses, a massive Coca-Cola vending machine, a bottle of Coke sticking out of a seven-year-old's rucksack, a 30-something in a Coca-Cola T-shirt and numerous bottles of Dasani, Coca-Cola's brand of bottled water, being slurped by a school sports team that have arrived in tracksuits. Leaning back on the seat I can capture this entire scene within my field of vision. I am the odd one out, the exception to the Coke-drinking norm.

visited the Coke museum which is a testimony to the Company's history and its advertising blitzkriegs, and as I look around I realise I am witnessing a skirmish in one of those battles right now. In the immediate vicinity of my seat in the the airport lounge is a man-sized Coca-Cola fridge packed with Company products, an authentic Mexican diner serving drinks in Coke glasses, a massive Coca-Cola vending machine, a bottle of Coke sticking out of a seven-year-old's rucksack, a 30-something in a Coca-Cola T-shirt and numerous bottles of Dasani, Coca-Cola's brand of bottled water, being slurped by a school sports team that have arrived in tracksuits. Leaning back on the seat I can capture this entire scene within my field of vision. I am the odd one out, the exception to the Coke-drinking norm.

Â

Coca-Cola is the biggest brand in the world, they have a greater global reach than a flu virus, they have lawyers who excrete spare IQ points and I am a dad sitting in an airport holding a teddy bear and an asthma inhaler muttering, âOh God, what have I doneâ¦'

1

THE HAPPINESS FACTORY

Atlanta, USA

âCoke is like a little bottle of sparkle-dust.'

Inside the Happiness Factory

, The Coca-Cola Company âdocumentary'

, The Coca-Cola Company âdocumentary'

Â

Â

E

veryone tells stories and a good story is a sleight of hand, distracting where needs be and discerning in its revelations. But the craftiest storytellers can tell you a tale without you realising it's being told. They are called advertisers - though some prefer the word âtwat'. Every product they sell has a tale to tell and an audience in mind to tell it to. They can tell a story with a phrase, a picture and sometimes with a single pencil line. Without them transnationals would become extinct because in order to sell they have to tell stories. They have to tell them to survive. Without adverts, brands do not exist and without brands modern corporations crumble.

veryone tells stories and a good story is a sleight of hand, distracting where needs be and discerning in its revelations. But the craftiest storytellers can tell you a tale without you realising it's being told. They are called advertisers - though some prefer the word âtwat'. Every product they sell has a tale to tell and an audience in mind to tell it to. They can tell a story with a phrase, a picture and sometimes with a single pencil line. Without them transnationals would become extinct because in order to sell they have to tell stories. They have to tell them to survive. Without adverts, brands do not exist and without brands modern corporations crumble.

Â

No company spends money unless they feel it is for their financial benefit, so consider the estimated total global advertising budget for 2008: it is US$665 billion

1

, or to use its

technical term a âgazillion'. With that amount of money you could run the UN and its entire operations for 33 years

2

. Or you could finance a totally new âWar on Terror'

3

: the US could invade North Korea and Cuba and still have change for a fair crack at France. For lovers of traditional forms of statistical comparison, the global advertising budget is Liberia's GDP for 600 years

4

.

1

, or to use its

technical term a âgazillion'. With that amount of money you could run the UN and its entire operations for 33 years

2

. Or you could finance a totally new âWar on Terror'

3

: the US could invade North Korea and Cuba and still have change for a fair crack at France. For lovers of traditional forms of statistical comparison, the global advertising budget is Liberia's GDP for 600 years

4

.

Â

In the battle of the brands Coca-Cola are king. In 2007 news spread across the globe's financial networks that for the sixth year in a row Coca-Cola had been ranked as the world's top brand, beating well-known competition from Microsoft, McDonald's, Disney, IBM and Nokia to the title

5

.

Business Week

/Interbrand annual ratings and its evaluations are based on a distinct criteria: the belief that brands can be intangible assets, ie, something that doesn't physically exist yet can nonetheless have a financial worth. The value of a brand is calculated through surveys, which essentially measure the goodwill felt towards a company. Now I'm not an expert on high finance but the day that the trader or banker came up with the idea that you could put a price onâ¦erâ¦nothing tangible - well, that day must have ended very late at night with a taxi driver helping them to the front door.

5

.

Business Week

/Interbrand annual ratings and its evaluations are based on a distinct criteria: the belief that brands can be intangible assets, ie, something that doesn't physically exist yet can nonetheless have a financial worth. The value of a brand is calculated through surveys, which essentially measure the goodwill felt towards a company. Now I'm not an expert on high finance but the day that the trader or banker came up with the idea that you could put a price onâ¦erâ¦nothing tangible - well, that day must have ended very late at night with a taxi driver helping them to the front door.

Â

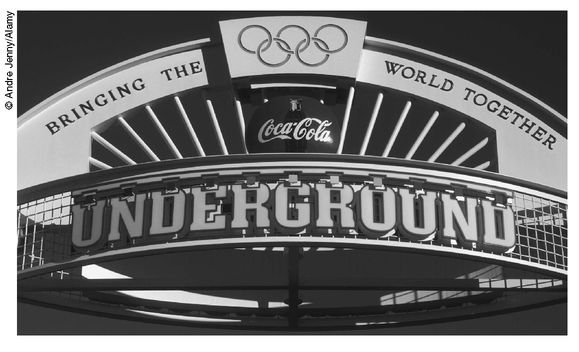

Interbrand valued the Coca-Cola brand at $65.324 billion, which is a lot of goodwill. And the company must fight for every penny of it. For take away the brand, the image, the red and white colours and iconic script, take away the shape of the bottle, the advertising, the polar bears, the lights in Times Square, the Santa ads at Christmas, the Superbowl commercials, the sponsorship of the Olympics and football leagues, take all that away and you are left with the product: brown fizzy sugar water. And brown fizzy sugar water with no

packaging, no logo and no built-in aspirations concocted in advertising land is not something any of us really need. Asa Chandler, Coke's first proprietor, knew this and set to conquering the world with a simple philosophy: advertise everywhere and make sure the drink is always available.

packaging, no logo and no built-in aspirations concocted in advertising land is not something any of us really need. Asa Chandler, Coke's first proprietor, knew this and set to conquering the world with a simple philosophy: advertise everywhere and make sure the drink is always available.

Â

But there is one crucial thing about storytelling, as any narrator knows: the details that are left out of a story are as important as those that are left in. I am about to be reminded of this as I head for the World of Coca-Cola, a smooth silver building, with metal curves and a gleaming tower, half-corporate HQ, half-Bond-villain lair. It is essentially the Coke museum, the repository of the official Coke story, but this corporate autobiography leaves out some of the more uncomfortable truths.

Other books

Flying Fur by Zenina Masters

Sanctum (The After Light Saga) by Cameo Renae

The Shadow Soul by Kaitlyn Davis

The Society of Dread by Glenn Dakin

City of Spades by Colin MacInnes

Wedding Song by Farideh Goldin

Master of Seduction by Kinley MacGregor

Regency Wagers by Diane Gaston