Belching Out the Devil (21 page)

Read Belching Out the Devil Online

Authors: Mark Thomas

Â

I take a good look at Ed Potter, a mere arms' length away. He is slowly doodling a large picture of a Coke bottle on an A4 pad, complete with curve lines and a passable imitation of the classic script.

Â

Finally the floor is thrown open to queries, observations and comments. Someone from British American Tobacco asks about the forgotten plight of poor farmers in developing countries. And is taken seriouslyâ¦If ever you want a measuring stick for CSR then this might be the moment, when a representative from British American Tobacco asks about workplace rights and security for farmers and doesn't get laughed out of the room.

Â

The interventions continue apace. Journalists from the

Independent

and

Corporate Age

ask about the effectiveness of CSR and how to improve it. Points are made from the floor about the increasing feminisation of poverty and questions raised about the relationship of neo-liberal globalisation to CSR.

Independent

and

Corporate Age

ask about the effectiveness of CSR and how to improve it. Points are made from the floor about the increasing feminisation of poverty and questions raised about the relationship of neo-liberal globalisation to CSR.

Â

But Ed Potter is still attracting flak and is heckled by members of the Colombian Solidarity Campaign, keen to question The

Coca-Cola Company's response to the murders of trade unionists in Colombia. We are about to learn that Ed Potter's twenty-three years' experience as an American lawyer has made him a blackbelt at avoidance. He deftly draws a line between the bottlers in Colombia and The Coca-Cola Company in Atlanta, the way the Company has always done. âThe situation to which you are describing is one that involves our independent bottlers in Colombia,' he says, that is an issue that Coca-Cola FEMSA [the current Colombian bottlers] can address.'

Coca-Cola Company's response to the murders of trade unionists in Colombia. We are about to learn that Ed Potter's twenty-three years' experience as an American lawyer has made him a blackbelt at avoidance. He deftly draws a line between the bottlers in Colombia and The Coca-Cola Company in Atlanta, the way the Company has always done. âThe situation to which you are describing is one that involves our independent bottlers in Colombia,' he says, that is an issue that Coca-Cola FEMSA [the current Colombian bottlers] can address.'

Â

Amnesty's man picks up this particular point when it is his turn to respond to questions, arguing that human rights and labour rights should be treated as a quality-control issue.

If a bottle was contaminated by the bottlers in Colombia, distributed around the world and affected people's health, âwould Coca-Cola have tried to distance themselves from the responsibility? Would they say that it is not their responsibility, it is that of their franchise bottling plants? I don't think they would say that. And they would not be allowed to.' So argued Amnesty's man adding, âany products we consume that have human rights' violations in their making should be seen as a defective product.' In essence, if Coca-Cola can treat contaminated product as its responsibility then they should do the same for human rights abuse.

Â

And this must apply to everyone The Coca-Cola Company works with, from the bottlers, to the distributors, to the sugar refineries, to the plantation workers - every single man, woman and subcontracted jack of them. It is not enough, said Amnesty, to be âcommitted to working with and encouraging them [that is, the independent bottling partners] to uphold the principles in the policy [i.e., workplace rights]'. Amnesty argue that all parts of Coke's supply chain should regard human and labour rights as âa compliance issue and [there] has to be

sanctions against their suppliers, just as there would be if there were any technical defect in the product.'

sanctions against their suppliers, just as there would be if there were any technical defect in the product.'

Â

This seemed like an appropriate point to jump in and try and muscle an answer out of Ed Potter, so I ask âWhen are you going to introduce codes of conduct for subcontractors and what measures are you going to bring in to enforce it?'

Â

Ed Potter looks through his thin glasses directly at me. His soft voice gets a rasp around its edge. He stops still and slowly says âThe question you are asking is a question that keeps me up at night.' He said it in such a way that I would not have been shocked if he had pulled out an acoustic guitar and sung his reply Johnny Cash-style. Then in true lawyer fashion he promptly ignores my question and asks the question he wants to answer, namely, âWhat is the most effective way that a company can address workplace rights issues not only for ourselves but our independent bottlers and in the supply chain?' And how does Ed Potter answer his own question? He doesn't! He waffles evasively and manages to even dodge his own question. He must have been one hell of a lawyer.

Â

As politicians and celebrities will concur, the distance between the finish of a formal occasion and the start of the car journey home, is measured not in minutes or metres but mishaps. It is in this arena that punches and eggs are thrown, knickers and ignorance shown and questions and answers improvised. Here you are not limited to asking one question and waiting for a morsel of a reply, here be dragons, arguments, oaths and curses. Any fool can wander into this unscripted landscape and they frequently do. So as the debate closes and the chair reads out the details of the next event over the sound of scraping chairs, the PR minders are on the alert. Ed Potter stands to pack his briefcase, inserting the doodle of a coke

bottle, kept safe for a possible framing at a later date. Or maybe when the board ask him, âWhat got done in London?' he can just hold up the picture with a smile.

bottle, kept safe for a possible framing at a later date. Or maybe when the board ask him, âWhat got done in London?' he can just hold up the picture with a smile.

Â

Ed Potter already has a couple of people vying for his attention.

âMr Potter,' I interrupt, â I wonder is there any chance we could arrange a time to have a quick chat about some of the issues?'

âUmâ¦wellâ¦' he says looking over my shoulder seeking assistance from a minder, âWellâ¦Iâ¦er.'

Â

He is interrupted by a woman in her thirties, with long dark hair and a slightly clipped Home Counties' accent. She is Communications Director at Coca-Cola Great Britain and she is professionally polite, by which I mean she is wary, motivated and undoubtedly the product of numerous management training programmes.

âCan I help?'

âI just wanted to try and get five minutes with Ed Potter.' Her answer is sure-footed and rapid fire, âI can see if we can sort something out. It might be possibleâ¦' she says flicking her hair, first one way and then the next, all the while keeping intense eye contact, giving her the appearance of a barn owl advertising shampoo. Then quickly changing tack, almost urgently she says, âLook, what do you want, Mark?'

âPardon?'

âWhat do you want? What is it you want us to do? I mean you are looking at a company that is trying to change. They want to change!'

âDo they?'

âYou are pushing at an open door.'

âWell, the company could try answering my questions to themâ¦'

Another minder is moving towards us, Ed has extracted himself from the gaggle and is heading to the door with one of Coke's PR/security people in tow, but they have been momentarily distracted by one of the crowd and peel off from Ed Potter. Seeing him leaving I blurt, âExcuse me' and lunge after him.

âMr Potter I wonderâ¦'

âI have to goâ¦I have a planeâ¦' he says pointing to the door.

I press on, âYou'll be at the company annual general meeting in Delaware in April?'

âErâ¦Yeah. Yeah I will.'

âWell I'm coming to the States for that too, so maybe we can grab five minutes for a chat?' On his own and with no minders in earshot maybe, just maybe he will say yes.

âWell if it was up to meâ¦you know, back when I was a lawyer I would have said yesâ¦but erâ¦.' he motions with his hand at the incoming group of PR closing towards us. They push past chairs, in their immaculate dark clothes, with speed and stealth.

âIn principle would you mind?' I hurriedly say to Ed Potter.

âIn principle, no, I don't mindâ¦'

âWell, if you don't mind in principle it is just a matter of logistics isn't it?'

Â

The question hangs in the air for a second before a woman with bundled hair and a US accent says, âTalk to Lauren about it. We'll see if we can sort something out.' She takes Ed Potter's elbow. Two other Coca-Cola people have appeared at his other side, âHe has to go,' says one of them.

Â

The hair flicker appears behind me. âWe'll try and sort something out. Here let me give you my number.'

Â

I turn back and Ed Potter is almost out of the room in a phalanx of Coca-Cola employees. And in the confusion I

thought I saw one of the Coke people in a suit and shades talk into the sleeve of his jacketâ¦But I could be making this bit up.

thought I saw one of the Coke people in a suit and shades talk into the sleeve of his jacketâ¦But I could be making this bit up.

POSTSCRIPT

Ed Potter and Coca-Cola declined a formal interview.

Â

When I returned home after the debate my wife Jenny was helping our daughter with her homework. I interrupted them, telling Jenny of my meeting with Clare from Human Resources and her comment that I was picking on Coke because they were an easy target. My wife looked up briefly from a page of equations and said, âIf they are worried about being such an easy target tell them they shouldn't be so crap.'

8

LET THEM DIG WELLS

Nejapa, El Salvador

âWe are commited to working with our neighbors to help build stronger communities and enhance individual opportunity.'

The Coca-Cola Company

1

1

Â

Â

T

he second leg of my visit to El Salvador is far from the sugar plantations and the coastal tides, but it does find the film crew and I once more ensconced in a hire van currently traversing a four-lane intersection somewhere in San Salvador - the capital. All of us are screaming, braced against the seat in front and are wide-eyed with panic as we are just experiencing a 50-mile-an-hour near collision with a six-foot portrait of Jesus. In El Salvador there are few rules of the road and even fewer observances of them. The only traffic regulation that everyone seems to obey is the strict ban on any

kind of signalling. Thus it was that a large municipal bus abruptly changed lanes lurching in front of our speeding van with all the calm precision of a drunk staggering for the toilet. The bus is one of the old US school-style buses, it's dented, rusty and looks like it has just escaped from a Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers cartoon, it is also covered in religious iconography, prayers, crucifixes and a life-size Jesus painted in blue on the back of the bus.

he second leg of my visit to El Salvador is far from the sugar plantations and the coastal tides, but it does find the film crew and I once more ensconced in a hire van currently traversing a four-lane intersection somewhere in San Salvador - the capital. All of us are screaming, braced against the seat in front and are wide-eyed with panic as we are just experiencing a 50-mile-an-hour near collision with a six-foot portrait of Jesus. In El Salvador there are few rules of the road and even fewer observances of them. The only traffic regulation that everyone seems to obey is the strict ban on any

kind of signalling. Thus it was that a large municipal bus abruptly changed lanes lurching in front of our speeding van with all the calm precision of a drunk staggering for the toilet. The bus is one of the old US school-style buses, it's dented, rusty and looks like it has just escaped from a Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers cartoon, it is also covered in religious iconography, prayers, crucifixes and a life-size Jesus painted in blue on the back of the bus.

Â

Suddenly finding ourselves inches away from Jesus and imminent death we all scream âFuck!!!!!!!' directly at the Son of God. The van brakes in a haze of tyre-shredding smoke and the battered bus pulls ahead. Jesus looks at us, standing in his robes, hands spread at his sides, almost shrugging, as if to say, âWhat can I do about it?' And as the adrenalin begins to subside and we begin to extract our fingers from seat-rests the irony of dying in a collision with the Lord begins to sink in. It occurs to me that in this highly religious country it must be strangely comforting if a pedestrians last thoughts are, âI've just been run over by Jesus.'

Â

Prior to my arrival all that I knew about El Salvador had been learnt from a T-shirt. Back in the 1980s T-shirts were a major source of information, especially for the Left. If there was a subject you didn't understand, all you had to do was to turn up at a demonstration and read the appropriate garment. Every social movement in the world had a shirt. It seemed as if revolutionaries had given up on seizing radio stations and at the first whiff of rebellion would storm the local flea market and surround the âYour name or picture printed here' stall.

Â

The particular T-shirt I'm referring to was owned by a supporter of the El Salvador solidarity campaign. Printed on it was a map showing El Salvador to be in Central America,

somewhere under Mexico and above Panama. Given that most countries in Central America have been subject to US intervention of sort, it was almost inevitable that the accompanying slogan was âUS OUT OF EL SALVADOR'. So I imagined the place to be full of armoured cars, goose-stepping soldiers and generals in dark glasses with a penchant for putting jump leads on opponents' genitals. Which at one point it was. The civil war lasted twelve years and ended in 1992. According to the CIA out of a population of just under 7 million, a total of 75,000 people lost their lives in the war.

2

Others put the number at 300,000 killed, though no one gives a figure for how many of these deaths were caused by buses.

somewhere under Mexico and above Panama. Given that most countries in Central America have been subject to US intervention of sort, it was almost inevitable that the accompanying slogan was âUS OUT OF EL SALVADOR'. So I imagined the place to be full of armoured cars, goose-stepping soldiers and generals in dark glasses with a penchant for putting jump leads on opponents' genitals. Which at one point it was. The civil war lasted twelve years and ended in 1992. According to the CIA out of a population of just under 7 million, a total of 75,000 people lost their lives in the war.

2

Others put the number at 300,000 killed, though no one gives a figure for how many of these deaths were caused by buses.

Â

Driving through the city Armando, our translator and driver, is lecturing us on its dangers. âWe have so many gangs here and so many guns. It is terrible. You have to be careful of the gangs it is a real problem. Seriously, this is the most violent problemâ¦' Then as we circumnavigate a roundabout he stops mid flow and says âI hate this place!'

Â

He is referring to what appears to be a memorial, a plinth and possibility the tallest flagpole I have ever seen, it must be at least five stories high at least and dominates the whole area. âWhat's written on the plinth?'

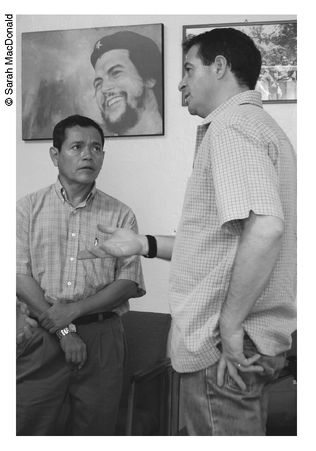

â“Patriotism Yes, Communism No.” It's a very famous quote made by Major Roberto D'Aubussion' He navigates the roundabout pausing briefly âThis guy, D'Aubussion he was the father of the death squads here.'

Other books

Two Friends by Alberto Moravia

Love UnCharted (Love's Improbable Possibility) by Belvin, Love

Nell by Nancy Thayer

Light Action in the Caribbean by Barry Lopez

The Naked and the Dead by Norman Mailer

The Hidden Man: A Phineas Starblower Adventure (Phineas Starblower Adventures) by Giles, Lori Othen

As Lie The Dead by Meding, Kelly

Romancing Rudy Raindear (Sexy Secret Santas) by Leo, Mary

True Divide by Liora Blake

A Galaxy Unknown 10: Azula Carver by Thomas DePrima