Belching Out the Devil (38 page)

Read Belching Out the Devil Online

Authors: Mark Thomas

As an atheist son of a family of preachers I have a bastardised version of the supposed Christian credo, âLove the sinner, hate the sin', namely âLove the religious, hate the religion'. It is impossible for me to fault anyone for wanting to buy a bottle of Coke over brewing maize for eight days, and believing basil takes away bad energy is no more bizarre than thinking a wafer turns into Jesus' body when it hits your tongue. But Coke and Pepsi have managed to inveigle their way into a ceremony that is an intrinsic part of these people's identity. They have once again become woven into the fabric of ordinary lives and special memories and I wonder if the children in the church will remember drinking Coke with their grandparents on the pine-needle floor. In these circumstances it is entirely possible to âLike the drink, loathe the company'.

14

WE'RE ON A ROAD TO DELAWARE

Wilmington, USA

âIf the communities we serve are in and of themselves not sustainable, then we do not have a sustainable business.'

Neville Isdell, The Coca-Cola Company, 2008

1

1

Â

Â

T

he city of Wilmington in the state of Delaware is about ninety minutes and three decades south of Brooklyn. The best thing about the place is that it is effortlessly forgettable. This is not where I envisaged ending my journey. Having stood on the banks of an oasis in the desert of Rajasthan, watched cane fields of fire turn the sky orange in El Salvador and marvelled at the mountain mist tumbling down the steep hillsides of Bucarmanga and into bustling streets of the city itself; Delaware is not the geographical dénouement I was hoping for. I have travelled thousands of miles, through squalor and splendour, meeting people with courage and tenacity searching for the political equivalent of what Spalding Gray would have called a âperfect moment'.

If I was on daytime TV I would call it âclosure', if I was a lawyer - a âresolution', I suppose I want to know what the fuck this has all been about and I have a niggling feeling that Wilmington is a resolutely âepiphany-free zone.' I am not doing down Wilmington, I just didn't know that IKEA did a flat-pack town. And as soon as someone finds that Allen key this place will tighten up just nicely.

he city of Wilmington in the state of Delaware is about ninety minutes and three decades south of Brooklyn. The best thing about the place is that it is effortlessly forgettable. This is not where I envisaged ending my journey. Having stood on the banks of an oasis in the desert of Rajasthan, watched cane fields of fire turn the sky orange in El Salvador and marvelled at the mountain mist tumbling down the steep hillsides of Bucarmanga and into bustling streets of the city itself; Delaware is not the geographical dénouement I was hoping for. I have travelled thousands of miles, through squalor and splendour, meeting people with courage and tenacity searching for the political equivalent of what Spalding Gray would have called a âperfect moment'.

If I was on daytime TV I would call it âclosure', if I was a lawyer - a âresolution', I suppose I want to know what the fuck this has all been about and I have a niggling feeling that Wilmington is a resolutely âepiphany-free zone.' I am not doing down Wilmington, I just didn't know that IKEA did a flat-pack town. And as soon as someone finds that Allen key this place will tighten up just nicely.

Â

The Coca-Cola Company has its annual meeting of stock holders in Wilmington because the company is registered not in its southern home of Atlanta but up here in the north in Delaware, along with half the Stock Exchange who take advantage of this on-shore tax haven. The meeting is to take place in the Hotel du Pont âthe best hotel in town' a policeman tells me, which may be the case but a hotel owned by DuPont - the second-largest chemical company in the world - just doesn't conjure an image of pampered luxury. To be fair it does look like the kind of place that hosts a lot of corporate events, a place where managing directors pick up industry awards and trophy wives.

Â

Back in London I had taken Coca-Cola's PR people up on their offer to try and arrange an interview with Ed Potter, the company's Global Workplace Rights Director, who I had seen at the House of Commons. The likelihood of the company sanctioning such a meeting was never high, still I went through the process with the same grim lack of expectation with which my mum buys her lottery tickets every week - knowing it is not going to happen but still being slightly disappointed when that turns out to be the case. âIt's a No right now' said the mail from the company, as if this were only a temporary state of affairs.

Nonetheless this is the only chance I will have had of seeing the corporate titans of the world's most famous brand and I'm curious how they will handle the criticism levelled at them. But more than this I wanted to see if the company was changing, if all these campaigns and lawsuits struggles and fights were having an effect. In the House of Commons debates one of the PR people had said, âYou're looking at a company that wants to change.' And if that is the case here's the place to see.

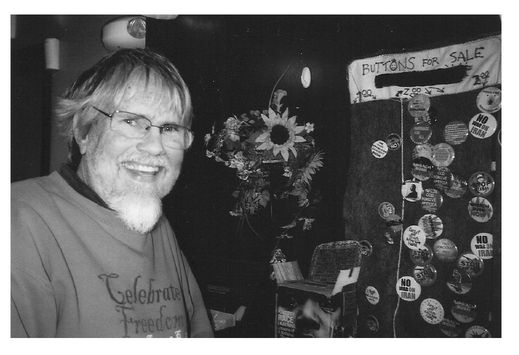

Ray Rogers has been described as a âlegendary union activist' and has been campaigning against Coca-Cola since 2003. He founded and runs the Corporate Campaign Inc who coordinate Stop Killer Coke.

2

Ray is making the now-annual pilgrimage to Delaware to challenge the company at the annual meeting. With him is Lew Freidman, a retired teacher who coordinates the websites, and the pair of them gave me lift from Brooklyn. Arriving at Wilmington, Ray runs off ahead of us while Lew and I chat as we amble over to the protest line opposite the hotel. This comprises primarily of clean, well-groomed, polite people in their early twenties who look a bit like market researchers for a Bible college as they smile and hand out seditious balloons with anti-corporate slogans on their innocent oval shapes.

2

Ray is making the now-annual pilgrimage to Delaware to challenge the company at the annual meeting. With him is Lew Freidman, a retired teacher who coordinates the websites, and the pair of them gave me lift from Brooklyn. Arriving at Wilmington, Ray runs off ahead of us while Lew and I chat as we amble over to the protest line opposite the hotel. This comprises primarily of clean, well-groomed, polite people in their early twenties who look a bit like market researchers for a Bible college as they smile and hand out seditious balloons with anti-corporate slogans on their innocent oval shapes.

Â

âMark!' shouts Ray as he runs across the road, momentarily disappearing behind a large truck. âMark!' he shouts again. Passing, the truck reveals Ray running toward a smartly dressed man who stands on the wrong side of the hotel's covered colonnade, adrift from the mass of shareholders milling towards the meeting. And I suddenly realise that Ed Potter has been caught in open ground.

When properly motivated I can multitask like a motherfucker. By which I mean I can cross a road, extract a digital recorder, turn it on, check the sound levels right, pop a pre-interview breath mint, grab a blast of Ventolin and reach Ed Potter before he can get to cover. Behind Coke's Global Workplace Rights Director a group of scaffolders work overhead, with mandatory hard hats and obligatory work belts, a few wear high-visibility orange vest and the place is covered in safety signs and warnings. It is under the appropriate sound of their hammering and sawing that I manage to interview Ed Potter. He smiles wanly as I wave the digital recorder at him and dive straight away into the case of the Indian workers in Kaladera being forced to work in dangerous conditions without the proper safety equipment.

âHow are you going to sort it out?' I enquire.

âI don't know the circumstances of India so I can't really comment directly on that but just like other issues that are, what I'll call systemic issues, we're working to resolve those,' he says.

Â

Ed Potter's voice is slightly thin, pitched at the tone of a man trying to clear his throat, so every now and again he has to go up a decibel to be heard above the building noise.

âHow would you deal with it?' I press.

âIf you email it to me we will definitely look into it.'

âIs there a procedure that you have for looking at this?'

âDo we have a written down procedure?' He repeats, eyebrows raised with his voice, âNoâ¦if you bring me a situation and location x, depending on what it is, we would put in an audit teamâ¦'

ââ¦But they say the only time we get given gas masks and gloves to work in the water treatment plant is when the auditors come round.'

âYou know,' he says shaking his head ruefully, âwe have the

same challenges as any national government will have with respect to people who may want to manipulate the outcome.'

same challenges as any national government will have with respect to people who may want to manipulate the outcome.'

Â

But the real issue is not just tracking down these abuses but how the company acts to solve them, so I ask what the sanctions are for bottlers who commit this kind of labour rights' abuse.

âWell, in the case of the supplier, a supplier who fails to take corrective action is subject to not being a supplier any more, that's the sanction.'

Â

Assuming that this is the case, that bottlers have their franchise removed, how will it work in this instance? Coca-Cola is the bottler. Or at least it is a direct subsidiary - the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverage Pvt Ltd is owned by The Coca-Cola Company.

3

3

Â

From under the hotel covered entrance a Coca-Cola man has spotted Ed Potter talking alone and unguarded and has come over to keep an eye on things. The man introduces himself as âTom, Head of Public Affairs'. To be fair to Ed Potter he stays and answers the questions, his thin hair blowing slightly. I am keen to get some action taken on the situation in India and press Ed Potter once more on the course the company will take.

âThese guys are going in, and not working with the proper safety equipment, is this serious enough to investigate?' I ask.

âWell, of course! Health and safety is one of ourâ¦things.'

âSo if I come to you and say this is happening hereâ¦'

The Public Affairs man nods firmly, âWe'll go and look.'

âYou'll go and look.'

âYeah, of course,' says Ed Potter.

D

ays later I emailed Ed Potter asking how we might proceed on this issue. The reply I got reads: Ed Potter has referred your email to me. You can find information about our workplace practices on both

cokefacts.com

and on

www.GetTheRealFacts.co.uk

.

ays later I emailed Ed Potter asking how we might proceed on this issue. The reply I got reads: Ed Potter has referred your email to me. You can find information about our workplace practices on both

cokefacts.com

and on

www.GetTheRealFacts.co.uk

.

Â

Sincerely,

Kari Bjorhus

Which seems a long way away from the response of âwe'll go and look'.

O

verhead the casual yells and hollers of building work continue as metres away the shareholders start to gather around the hotel entrance while police officers with Secret Service earpieces watch over them. So before time wears our encounter to a close and we too must herd inside I say, âColombia. Isidro Gil. I spoke to people who saw him killed - someone was shot and killed on Coca-Cola's property.' Tom from Public Affairs says âWe understand that.'

verhead the casual yells and hollers of building work continue as metres away the shareholders start to gather around the hotel entrance while police officers with Secret Service earpieces watch over them. So before time wears our encounter to a close and we too must herd inside I say, âColombia. Isidro Gil. I spoke to people who saw him killed - someone was shot and killed on Coca-Cola's property.' Tom from Public Affairs says âWe understand that.'

âWe get it,' joins Ed Potter.

âWe understand that he was an employee. We understand that he was shot thereâ¦It's a very difficult area, it was a very difficult time. If we can come to some resolution, we'd like to help that family and move on.'

Â

But it quickly descends from that compassionate line into the usual company statements, hiding in the mire of the âCoca-Cola system'. Ed Potter describes the dead as men who âwere not current or ever Coca-Cola employees'. He parrots the company mantra, seemingly oblivious to the fact that the refusal of the Company to acknowledge they have a

responsibility over âthe Coca-Cola system' is the very thing that gets them into so much grief. People don't much care for the lawyerly lines of separation between legal entities - if your name is on the label you have got the responsibility.

responsibility over âthe Coca-Cola system' is the very thing that gets them into so much grief. People don't much care for the lawyerly lines of separation between legal entities - if your name is on the label you have got the responsibility.

Other books

The Destruction of the World by Fire by Shiden Kanzaki

Countdown to Zero Hour by Nico Rosso

Baby Comes First by Beverly Farr

Claire De Lune by Christine Johnson

Moonlight Menage by Stephanie Julian

Make a Wish! by Miranda Jones

Wolf at the Door by Davidson, MaryJanice

Final Call by Reid, Terri

The True Love Quilting Club by Lori Wilde

Shotgun Bride by Lopp, Karen