Belle (18 page)

Authors: Paula Byrne

On 29 November the suggestion was made to destroy part of the slave cargo in order to protect the rest. That evening, at 8 p.m., fifty-four women and children were pushed through cabin windows into the sea. Two days later, forty-two men were thrown overboard. Ten jumped voluntarily. On the third day a final group of thirty-six men was dispatched. One man clambered back aboard the ship.

James Kelsall later stated that the slaves were fit and healthy, but this would be disputed by many abolitionists.

Between the first and last massacre, on 1 December, heavy rain fell, replenishing the water supplies. At one point, a slave appealed for their lives to be spared, but he was ignored.

One of the most horrifying massacres in the terrible history of the slave ships had occurred. But nobody would have heard of it had the Gregson syndicate not made the tactical mistake of claiming insurance for the ‘cargo’ that had been jettisoned. The insurers refused to pay up, and the case went to court. There was never a case for murder. It was an insurance claim. And insurance was Lord Mansfield’s speciality.

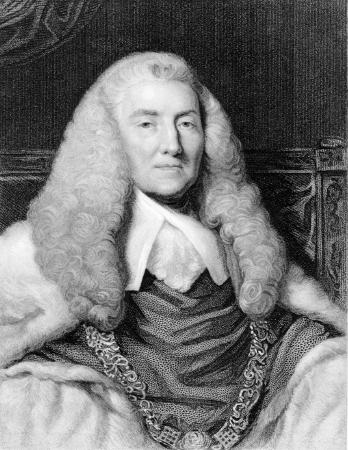

Mansfield as Lord Chief Justice, engraving after a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds

The life of one Man is like the life of another Man whatever the Complexion is, whatever the colour

Mr Pigot, counsel for the insurers

When the news of the

Zong

massacre reached England, the Gregson syndicate immediately set about claiming compensation from their underwriters for the loss of the slaves. Legal proceedings began when the insurers refused to pay up. The dispute was initially tried before a jury at the Guildhall in London on 6 March 1783. Overseeing the trial was Dido’s adoptive father, Lord Chief Justice the Earl of Mansfield, the world expert on maritime insurance.

The question centred upon whether Collingwood had or had not jettisoned his (human) cargo as a matter of necessity, under ‘perils of the sea’. Eighteenth-century slave ships could be insured against several forms of ‘perils of the sea’, including shipwreck, piracy, arrest and shipboard rebellion, but the death of slaves owing to what was deemed ‘natural death’ (that is, through sickness, or want of water or food) was uninsurable.

If the slaves had died onshore, the Gregson syndicate would have had no redress from their insurers. But if some slaves were jettisoned in order to save the rest of the ‘cargo’ or the ship herself, then a claim could be made under the notion of ‘general average’. This principle held that a captain who jettisoned part of his cargo in order to save the rest could claim for the loss from his insurers.

At this trial the jury decided in favour of Gregson, that the insurers (Gilbert) were liable to pay compensation for the 132 Africans ‘jettisoned’ from the

Zong

. The freed slave and well-known London figure Olaudah Equiano went to see Granville Sharp on 19 March, and the following day Sharp sought legal advice on the possibility of prosecuting the ship’s crew for murder.

In the meantime, Gilbert fought back and asked for a retrial, and on 21–22 May there was a two-day hearing at the Court of King’s Bench at Westminster Hall to review the evidence.

1

Almost all the information we have about the

Zong

case derives from this hearing, as Lord Mansfield’s notes for the original trial in March are missing.

2

Once again, Granville Sharp was to prove a thorn in the side of Mansfield. He appeared at the May hearing alongside his secretary, who transcribed the whole proceedings.

As Lord Mansfield stated in his opening remarks, the

Zong

was ‘a very singular case’. The first thing he did was to emphasise that this was an insurance claim, not a murder trial, but it was clear that much was at stake. In his summing-up of the March trial, he made a comment that has (unfairly) been used to smear his reputation: ‘The matter left to the jury, was whether it was from necessity: for they had no doubt (though it shocks one very much) that the Case of Slaves was the same as if Horses had been thrown over board. It is a very shocking case.’

3

Some historians are convinced that this statement shows Mansfield’s personal opinion,

4

though it seems clear that he is in fact stating the views of the jury.

Robert Stubbs appeared as the only witness, claiming that there was ‘an absolute Necessity for throwing over the Negroes’, because the crew feared that all the slaves would die if they did not throw some into the sea.

5

The insurers argued that Collingwood had made ‘a Blunder and Mistake’ in sailing beyond Jamaica, and that the slaves had been deliberately killed so their owners could claim compensation. They argued that this was a case of fraud and human error, and that therefore they should not be liable.

Strikingly, however, Gilbert’s lawyers moved the argument beyond a mere insurance claim, emotively describing the affair as a ‘Crime of the Deepest and Blackest Dye’, and saying that the crew had lost ‘the feelings of Men’.

6

The historian James Walvin has argued persuasively that the somewhat alarming presence of Granville Sharp and his secretary in court had a significant bearing on the tone and language of this hearing. Murder had been on no one’s mind at the Guildhall sessions two months before, but the word was used nine times at the King’s Bench.

7

One of Gilbert’s lawyers, the fierce Mr Pigot, who comes out of the case particularly well, made an assertion that made it very clear that this was much more than an insurance claim: ‘The life of one Man is like the life of another Man whatever the Complexion is, whatever the colour.’ He demanded that the grotesque acts that had taken place on board the

Zong

should lead to a retrial.

The turning point for Lord Mansfield appears to have been a shocking detail that had hitherto been undisclosed. He learned that the last group of thirty-six slaves ‘were thrown overboard a Day after the Rain’. Mansfield’s comments are most revealing: ‘a fact which I am not really apprized of … I am not aware of that fact … I did not attend to it … it is new to me. I did not know any Thing of it.’ The whole case rested on the assumption that the slaves were killed out of necessity, yet it was now clear that the water supplies had been replenished. In an affidavit made by Kelsall it was reported that on 1 December it rained heavily for more than a day, allowing six butts of water (sufficient for eleven days) to be collected.

8

It was at this juncture that Lord Mansfield recommended a retrial: ‘It is a very uncommon Case and I think very well deserves a re-examination.’

The three judges concluded that the case for necessity in jettisoning the slaves was not proven. Despite this turnaround, a second trial never took place. It seems that Gregson dropped his claim. One suspects that the syndicate knew they would lose, and that the negative publicity would be catastrophically damaging to the entire cause of the trade. Gregson and his colleagues did not win their compensation, which was a victory of some sort for Sharp and the early abolitionists, but neither were they prosecuted for murder.

Lord Mansfield comes out of this case somewhat ambiguously. On the one hand, he ordered the retrial of

Gregson v Gilbert

once he had learned that the heavens had opened and rain fell. But on the other, he did not refer the case to the Attorney General for a possible murder trial.

In 1785, two years after the

Zong

trial, Mansfield presided over another insurance case, where nineteen slaves had been killed in a munity and a further thirty-three had committed suicide. Mansfield said, ‘This was not like the case of throwing Negroes overboard to save the ship. Here there was a cargo of desperate Negroes refusing to go into slavery and dying of despair.’ The insurers, he ruled, should only be required to pay damages for the nineteen. To us, it seems shocking that a monetary value could in any circumstances be placed upon human beings, as if they were chattels. But for Mansfield, the law was the law. Clarity and certainty were, for him, more important than whether a particular law was good or bad: ‘The great object in every branch of the law … is certainty, and that the grounds of decision should be precisely known.’

9

The person who comes out of the

Zong

case most damnably is Solicitor General John Lee, who appeared at the hearing on behalf of the ship’s owners, and stated:

What is this claim that human people have been thrown overboard? This is a case of chattels or goods. Blacks are goods and property; it is madness to accuse these well-serving honourable men of murder. They acted out of necessity and in the most appropriate manner for the cause. The late Captain Collingwood acted in the interest of his ship to protect the safety of his crew. To question the judgement of an experienced well-travelled captain held in the highest regard is one of folly, especially when talking of slaves. The case is the same as if wood had been thrown overboard.

10

As for the real hero of the story, once again that was Granville Sharp. After the trial he wrote countless letters to highly placed individuals, contacted the press with a copy of his trial minutes, and tried to bring murder charges against Kelsall and his crew. He lobbied the Prime Minister, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty.

The immediate impact of the

Zong

massacre on public opinion may have been limited. But in the longer term, the breathtaking brutality of the murders, and the fact that drowned human beings could be reduced to an insurance claim brought home the urgency of abolishing the slave trade. It was because of Sharp’s efforts that the

Zong

massacre became an important topic in abolitionist literature: the massacre was discussed by Thomas Clarkson, Ottobah Cugoano, James Ramsay and John Newton – most of the great abolitionists. His attempts to instigate a prosecution for murder were to have important consequences, bringing together like-minded individuals who would play a leading role in the British anti-slavery movement, formally established in 1787.

One of these men was Thomas Clarkson, who became perhaps the key founding member of the abolition movement. His definitive

History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament

used the

Zong

massacre to illustrate the atrocities of the trade. Strikingly, Clarkson’s account puts forward yet another, and most compelling, theory of the motivation behind the killings, and one that has not been sufficiently explored: that the whole tale of the water shortage was a fabrication, and that the Africans thrown overboard were ill and diseased, and therefore worth more dead than alive.

11

Dido Belle, amanuensis to the Lord Chief Justice

Life at Kenwood was as idyllic as ever, but the security that Dido Belle had known with the Mansfields was about to change in the years after the

Zong

massacre. The first change came with the death of Lady Mansfield in 1784. Despite her reserves of energy, her health had been precarious since the stress of the Gordon Riots. Her husband was indefatigable in his efforts to nurse her. Newspapers reported that he ‘was most assiduous in the sick chamber, constantly administering what the phys-icians had ordered and sitting up several nights together’.

1

The Mansfields had always had a strong and happy marriage, despite their childlessness.