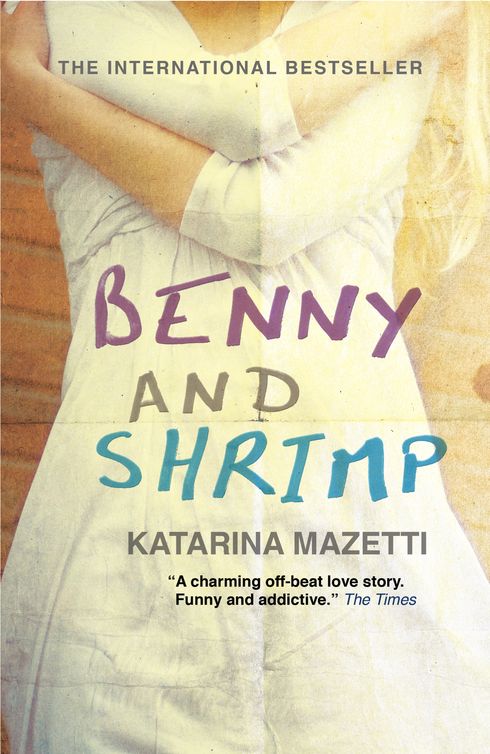

Benny & Shrimp

Authors: Katarina Mazetti

Praise for

Benny & Shrimp:

“A charming off-beat love story. Funny and addictive.”

The Times

“This offbeat, down to earth love story is refreshingly light to read, and addictive.”

The Observer

“Sweet and pleasingly down to earth. It is no wonder that Mazetti’s offbeat romance was a runaway bestseller in her native Sweden.”

Daily Mail

“

Benny & Shrimp

is a delightfully honest, sensitively told tale which gives new meaning to, ‘The course of true love never runs smooth.’ A compelling novel for the perfectly imperfect person in us all.” Jeanne Ray, author of

Julie and Romeo

“Share this book with others, but make sure your own copy is safe. For it’s a book to keep in your purse, pocket or backpack always. To have close at hand whenever life deals you a blow. It will restore your faith in love and goodness. And put a smile on your face.” Linda Olsson, author of

Astrid & Veronika

AND

SHRIMP

KATARINA MAZETTI

translated by Sarah Death

Who stands up for the dead?

Looks after their rights,

listens to their problems

and waters their pot plants?

You’ll have to be on your guard!

An aggrieved, single woman in a distinctly abnormal emotional state. Who knows what I might get up to at the next full moon?

You’ve read Stephen King, haven’t you?

I’m sitting by my husband’s grave, on a dark green bench worn smooth by use, and letting his headstone irritate me.

It’s a sober little chunk of natural stone with just his name on it – “Örjan Wallin” in the plainest of plain

lettering

. Simple, you might even say over-explicit, just like he was. And he chose it himself, too; left

instructions

with the funeral director.

Just a little thing like that. I mean, he wasn’t even ill.

I know exactly what message he was intending his stone to convey: Death is a Completely Natural Part of the Cycle. He was a biologist.

Thanks for that, Örjan.

I sit here in my lunch break several times a week, and always at least once at weekends. If it starts raining, I get out a plastic raincoat that folds away into a little purse. It’s hideously ugly; I found it in my mother’s chest of drawers.

There are lots of us with raincoats like that, in the cemetery.

I always sit here for at least an hour. Presumably in the hope of getting down to the right sort of grieving if I stick at it long enough. I’d feel better if I could feel worse, you might say. If I could sit here wringing out endless hankies without stealing constant glances at myself to check the tears were genuine.

The awful truth is, half the time, all I feel is furious with him. Bloody deserter, why couldn’t you watch where you were going? And my feelings the rest of the time are, I suppose, pretty much like those of a child who had a budgie for twelve years and then it died. There, I’ve said it.

I miss the constant companionship and all our daily routines. There’s no one rustling the paper on the sofa beside me; no smell of coffee when I come home; the shoe rack looks like a tree in winter without all Örjan’s boots and wellies.

And if I can’t work out the answer to “Sun god, two letters”, I have to guess it, or leave it blank.

One half of the double bed’s always neat.

Nobody’d worry where I’d got to if I didn’t come home because I happened to have been run over by a car.

And nobody flushes the loo if I’m not there.

So here I am, sitting in the cemetery, missing the sound of the flush. Weird enough for you, Stephen?

There’s something about cemeteries that always makes me think of some convulsive, second-rate

standup

comedian. Repression and gabbled strings of words, of course – but surely I can allow myself that? I haven’t much besides my little repressions to occupy me these days.

With Örjan, at least I knew who I was. We defined each other; after all, that’s what relationships between two people are for.

Who am I now?

I’m at the mercy of whoever happens to see me. For some I’m a voter, for others a pedestrian, a wage

earner

, a consumer of culture, a human resource or a

property

owner.

Or just a collection of split ends, leaking sanitary towels and dry skin.

Though of course I can still use Örjan for defining myself. He can do me that one, posthumous favour. If Örjan hadn’t existed, I could be calling myself a “single girl, thirty-something”; I saw that in a newspaper

yesterday

, and it made my hair stand on end. Instead, I’m a “young, childless widow”, so tragic, so very sad. Well, thanks for that too, Örjan!

Somewhere there’s a nagging little feeling of pure deflation, as well. I feel let down that Örjan went and died.

We’d planned our future, short and long term! A canoeing holiday in Värmland, and a high-yield pension scheme apiece.

Örjan should be feeling let down, too. All that tai chi, organic potato and polyunsaturated fat. What good did it do him?

Sometimes I’m outraged on his behalf. It’s not fair, Örjan! When you were so well-meaning and

competent

!

And there’s an excited little flutter between my legs now and then, after five months of celibacy. It makes me worry I’ve got necrophiliac tendencies.

Next to Örjan’s stone there’s a really tasteless

gravestone

, an absolute monstrosity. White marble with swirly gold lettering; angels, roses, birds, words on garlands of ribbon, even a salutary little skull and scythe. The grave itself is as crowded with plants as a garden centre. On the headstone are a man’s name and a woman’s name with similar dates of birth, so it must be a child honouring his father and mother in that

over-lavish

way.

A few weeks ago I saw the bereaved by the

monstrosity

for the first time. He was a man of about my age, in a loud, quilted jacket and a padded cap with earflaps. Its peak went up at the front, American-style, and had a logo saying FOREST OWNERS’ ALLIANCE. He was eagerly raking and digging his little plot.

There’s nothing growing around Örjan’s stone. He’d probably have thought a little rosebush totally out of keeping, since it wasn’t a species native to the

cemetery’s

biotope. And they don’t sell yarrow or

meadowsweet

in the flower shop at the cemetery gates.

The Forest Owner comes regularly every few days, about noon. He’s always loaded down with new plants and fertilisers. He seems to take great pride in his

gardening

, as if the grave were his allotment.

Last time, he sat down on the seat beside me and looked at me sideways, but he didn’t say anything.

He had a funny smell and only three fingers on his left hand.

Damn and blast! I can’t stand her, just can’t stand the sight of her!

Why’s she always sitting there?

I used to sit on the bench for a little while after I’d done the grave, and finish thinking all my interrupted thoughts, hoping to find a loose end to grab onto, to keep me plodding on through the next day or two. If I don’t keep my mind on the job, there’s inevitably some little disaster and I have to spend an extra day sorting it out. Like I run the tractor into a rock and break the back axle. Or a cow tramples one of her teats because I forgot to fix on her bra – I mean udder guard.

Going to the grave is my only breathing space, and even then I never feel I can just sit there thinking. I have

to rake and plant and weed before I can let myself sit down.

And then she’s there.

Faded, like some old colour photo that’s been on

dis

play

for years. Dried-out blonde hair, a pale face, white eyebrows and lashes, wishy-washy pastel clothes, always something vaguely blue or beige. A beige person. The total insolence of her – it would only take a bit of

make-

up

or bright jewellery to let the people around her know that here’s someone who at least cares what you see and what you think of me. All her paleness says is: I don’t give a damn what you think; I don’t so much as notice you.

I like a woman’s appearance to say: look at me, see what I’ve got to offer! It makes me feel sort of flattered. She should have shiny lipstick and little shoes with straps and pointed toes, and her breasts boosted up under your nose. It doesn’t matter if her lipstick’s a bit smudged, or her dress pulls tight over her spare tyre, or there’s hardly room for all her huge artificial pearls – not everybody can have good taste; it’s making the effort that counts. I always fall a little bit in love when I see a woman who’s not all that young any more but who’s invested half a day’s work in getting noticed, especially if she’s got long, false nails, hair permed to extinction and teetering high heels. It makes me want to hold her and cuddle her and pay her compliments.

I never do, of course. I never get nearer than

watch

ing

them in the post office or the bank; there are no women on the farm except the inseminator and the vet.

In long, blue rubber aprons, big boots, scarves tied round their hair, dashing in with a test tube of bull’s semen. And they never have time to stay for a cup of coffee – even assuming I’d had time to go in and make one.

Mum used to nag me in those last years to “go out” and find myself a girl. As if they existed somewhere, a flock of willing girls, and all you had to do was go out and select one. Like taking your rifle out in the hunting season to bag yourself a hare.

Because she knew, long before I did, that the cancer was slowly eating her from inside and I’d be left on my own. Not just with all the outdoor work to do, but also the many other things she’d provided over the years: a warm house, a freshly changed bed, clean overalls every other day, nice food, constant hot coffee with

home

made

buns. Backed up by all those jobs I’d never had to think about – chopping firewood, stoking the boiler, picking berries, doing the washing; all those things I don’t find time for now. Overalls stiff with cow shit and sour milk, grey sheets, the house cold whenever you come in, Nescafé stirred into a cup of hot water from the tap. And the jumbo sausage that splits in the microwave every bloody day.

She used to leave the family section of

The Farmer

open at the personal page beside my coffee. Sometimes she’d circle one of the ads. But of course, she never said anything outright.

What Mum didn’t know was that there are no young maids flocking around the milk churn platform any

more, eager to keep house for Eligible Bachelor With Own Farm. They all disappeared off to town some years back and now they’re nursery school teachers and

jun

ior

nurses and married to car mechanics and salesmen and thinking about buying a little house. Sometimes in the summer they come back here with their partner and some flaxen-haired bundle in a baby carrier, to laze on their backs in deckchairs outside their parents’ old farms for a few weeks.

Carina, who was always after me in upper secondary school and could be persuaded to do it if you chatted her up a bit, ambushes me now and then from behind the shelves in the village shop. The shop’s still open in summer; it might be good for a few more years. Suddenly she’ll jump out and pretend it’s a coincidence and start interrogating me about whether I’m married or have got any children. She lives in town now, with Stefan, who works as a storeman for the Co-op, she says triumphantly, looking as if she expects me to burst into tears at what I’ve missed out on. Like hell.

Maybe she, the pale woman, has parents to visit and laze on her back with in summer. It’d be nice to be rid of her for a few weeks. Though in summer there’s no time to come here, not unless it pours with rain one day and stops me getting on with the haymaking.

And that gravestone she sits staring at! What sort of a stone do you call that? It looks like something a

sur

veyor

put down as a boundary marker!

Mum chose Dad’s headstone; I can see it’s garish but I can also see all the love that went into choosing it. She

spent several weeks, ordered catalogues and everything. Every day she had some new idea for the design and in the end she went for the whole lot.

Örjan, is that her father, or a brother, or her bloke? And if she can bring herself to come here and sit staring at that stone day after day, why can’t she bring herself to put even one flowering plant on the grave?