Berlin 1961 (3 page)

Authors: Frederick Kempe

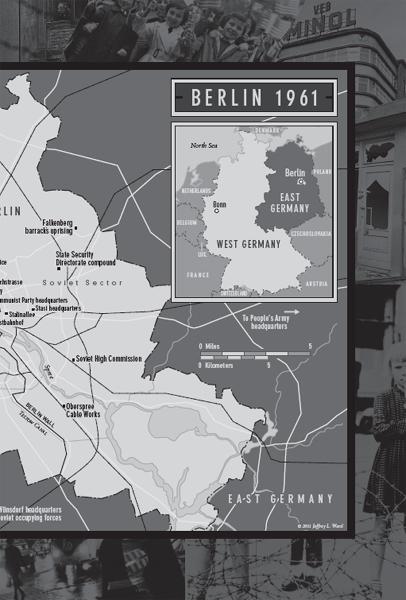

An American president’s inaugural year often can be perilous, even when its occupant is a more experienced one than Kennedy, as the burdens of a dangerous world are passed from one administration to another. And during Kennedy’s first five months in office, he would suffer several self-inflicted wounds, from his mishandling of the Bay of Pigs invasion to the Vienna Summit, where by his own account Khrushchev had outmaneuvered and brutalized him. Yet nowhere were the stakes higher for him than in Berlin, the central stage for U.S.–Soviet competition.

By temperament and upbringing, Khrushchev was Kennedy’s opposite. The sixty-seven-year-old grandson of a serf and son of a coal miner was impulsive where Kennedy was indecisive, and bombastic where Kennedy was measured. His moods alternated between the deep-seated insecurity of a man who had been illiterate until his twenties and the bold confidence of someone who had risen to power against impossible odds while rivals faded, were purged, or were killed. Complicit in his mentor Joseph Stalin’s crimes before renouncing Stalin after his death, in 1961 Khrushchev was vacillating between his instinct for reform and better relations with the West and his habit of authoritarianism and confrontation. It was his conviction that he could best advance Soviet interests through peaceful coexistence and competition with the West, yet at the same time pressures were growing on him to escalate tensions with Washington and by whatever means necessary stop the outflow of refugees that threatened to trigger East Germany’s implosion.

Between the establishment of the East German state in 1949 and 1961, one of every six individuals—2.8 million people—had left as refugees. That total swelled to 4 million when one included those who had fled the Soviet-occupied zone between 1945 and 1949. The exodus was emptying the country of its most talented and motivated people.

In addition, Khrushchev was racing against the clock as 1961 began. He faced a crucial Communist Party Congress in October, at which he had reason to fear his enemies would unseat him if he failed to fix Berlin by then. When Khrushchev told Kennedy during their Vienna Summit that Berlin was “the most dangerous place in the world,” what he meant was that it was the spot most likely to trigger a nuclear superpower conflict. Beyond that, Khrushchev knew that if he botched Berlin, his rivals in Moscow would destroy him.

The contest between the key supporting German actors to Khrushchev and Kennedy was just as charged, an asymmetrical conflict between East German leader Walter Ulbricht and his failing country of seventeen million people, and West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and his rapidly rising economic power of sixty million.

For Ulbricht, the year would be of even greater existential importance than it was for either Kennedy or Khrushchev. The so-called German Democratic Republic, as East Germany was officially known, was his life’s work, and at age sixty-seven he knew that without radical remedy it was heading for economic and political collapse. The greater that danger, the more intensively he schemed to prevent it. Ulbricht’s leverage in Moscow was growing in rough proportion to his country’s instability because of the Kremlin’s fear that East German failure would cause ripples across the Soviet empire.

Across the border in West Germany, the country’s first and only chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, was, at age eighty-five and after three terms, waging war simultaneously against his own mortality and against political opponent Willy Brandt, who was West Berlin’s mayor. Brandt’s Social Democratic Party represented to Adenauer the unacceptable danger of leftist takeover in the coming September elections. However, Adenauer considered Kennedy himself to be the greatest threat to his legacy of a free and democratic West Germany.

By 1961, Adenauer’s place in history would seem to have been assured through the phoenix-like rise of West Germany from the Third Reich’s ashes. Yet Kennedy considered him a spent force upon whom his U.S. predecessors had relied too much at the expense of closer relations with Moscow. Adenauer, in turn, feared Kennedy lacked the character and backbone to stand up to the Soviets during what he was convinced would be a decisive year.

The story of

Berlin 1961

is told in three parts.

Part I, “The Players,” introduces the four protagonists: Khrushchev, Kennedy, Ulbricht, and Adenauer, whose connecting tissue throughout the year is Berlin and the central role the city plays in their ambitions and fears. The early chapters capture their competing motivations and the events that set the stage for the drama that follows. On his first morning in the Lincoln Bedroom, Kennedy wakes up to Khrushchev’s unilateral release of captured airmen from a U.S. spy plane, and from that point forward the plot is driven by the two leaders’ jockeying and miscommunication. Meanwhile, Ulbricht works behind the scenes to force Khrushchev to crack down in Berlin, and Adenauer navigates life with a new U.S. president whom he mistrusts.

In Part II, “The Gathering Storm,” Kennedy reels from the botched U.S. effort to overthrow Castro at the Bay of Pigs and sees an opportunity to recover his endangered foreign policy standing through an arms buildup and a summit meeting with Khrushchev. The greatly increased refugee exodus from East Germany sharpens the crisis for Ulbricht, who intensifies his scheming to close the Berlin border. Ever mercurial, Khrushchev transforms himself from courting to undermining Kennedy at the Vienna Summit, where he tables a new, threatening Berlin ultimatum and expresses mock sympathy about his adversary’s demonstrated weakness. Kennedy is left disheartened by his own poor performance and grows preoccupied with finding ways to ensure that Khrushchev doesn’t endanger the world by miscalculating American resolve.

“The Showdown,” the book’s third and final part, documents and describes the dithering in Washington and the decisions in Moscow that result in the stunning nighttime August 13 border-closure operation and its dramatic aftermath. Privately, Kennedy is relieved by the Soviet action and hopes that the Soviets will become easier partners with the East German refugee matter solved. He quickly learns, however, that he has overestimated the potential benefits of a Berlin Wall. Dozens of Berliners engage in desperate escape attempts, some with deadly outcomes. Internationally, the crisis intensifies as Washington debates how best to fight and win a nuclear war, Moscow wheels its tanks into place, and the world holds its breath—just as it would again a year later when the ripples of Berlin 1961 would result in the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Sprinkled throughout the narrative are vignettes of Berliners themselves, who are buffeted by their involuntary role in a decisive moment of Cold War history: the survivor of multiple Soviet rapes who tries to tell her story to a people who just want to forget; the farmer whose resistance to land collectivization lands him in prison; the engineer whose flight to the West ends with her victory at the Miss Universe pageant; the East German soldier whose leap to freedom over coils of barbed wire, with his arm releasing his rifle in mid-flight, becomes the iconic image of liberation; and the tailor who is gunned down while trying to swim to freedom, the first victim of East German shoot-to-kill orders for would-be escapees.

Early in 1961, it was just as unthinkable that a political system would put up a wall to contain its people as it was inconceivable twenty-eight years later that the same barrier would crumble peacefully and seemingly overnight.

It is only by returning to the year that produced the Berlin Wall and revisiting the forces and the people surrounding it that one can properly understand what happened and try to settle a few of history’s great unanswered questions.

Should history consider the Berlin Wall’s construction the positive outcome of Kennedy’s unflappable leadership—a successful means of avoiding war—or was the Wall instead the unhappy result of his missing backbone? Was Kennedy caught by surprise by the Berlin border closure, or did he anticipate it and perhaps even desire it because he believed it would defuse tensions that might lead to nuclear conflict? Were Kennedy’s motivations enlightened and oriented toward peace, or cynical and shortsighted at a time when another course of action might have spared tens of millions of Eastern Europeans from another generation of Soviet occupation and oppression?

Was Khrushchev a true reformer whose efforts to reach out to Kennedy following his election were a genuine effort (that the U.S. failed to recognize) to reduce tensions? Or was he an erratic leader with whom the U.S. could never have done business? Would Khrushchev have backed off from the plan to build a Berlin Wall if he had believed Kennedy would resist? Or was the danger of East German implosion so great that he would have risked war, if necessary, to shut off the refugee flow?

The pages that follow are an attempt to shed new light, based on new evidence and fresh insights, on one of the most dramatic years of the second half of the twentieth century—even while we try to apply its lessons to the turbulent early years of the twenty-first.

PART I

THE PLAYERS

1

KHRUSHCHEV: COMMUNIST IN A HURRY

We have thirty nuclear weapons earmarked for France, more than enough to destroy that country. We are reserving fifty each for West Germany and Britain.

Premier Khrushchev to U.S. Ambassador Llewellyn E. Thompson Jr., January 1, 1960

No matter how good the old year has been, the New Year will be better still…. I think no one will reproach me if I say that we attach great importance to improving our relations with the USA…. We hope that the new U.S. president will be like a fresh wind blowing away the stale air between the USA and the USSR.

One year later, Khrushchev’s New Year’s toast, January 1, 1961

THE KREMLIN, MOSCOW

NEW YEAR’S EVE, DECEMBER

31, 1960

I

t was just minutes before midnight, and Nikita Khrushchev had reason to be relieved that 1960 was nearly over. He had even greater cause for concern about the year ahead as he surveyed his two thousand New Year’s guests under the towering, vaulted ceiling of St. George’s Hall at the Kremlin. As the storm outside deposited a thick layer of snow on Red Square and the mausoleum containing his embalmed predecessors, Lenin and Stalin, Khrushchev recognized that Soviet standing in the world, his place in history, and—more to the point—his political survival could depend on how he managed his own blizzard of challenges.

At home, Khrushchev was suffering his second straight failed harvest. Just two years earlier and with considerable flourish, he had launched a crash program to overtake U.S. living standards by 1970, but he wasn’t even meeting his people’s basic needs. On an inspection tour of the country, he had seen shortages almost everywhere of housing, butter, meat, milk, and eggs. His advisers were telling him the chances of a workers’ revolt were growing, not unlike the one in Hungary that he had been forced to crush with Soviet tanks in 1956.

Abroad, Khrushchev’s foreign policy of peaceful coexistence with the West, a controversial break with Stalin’s notion of inevitable confrontation, had crash-landed when a Soviet rocket brought down an American Lockheed U-2 spy plane the previous May. A few days later, Khrushchev triggered the collapse of the Paris Summit with President Dwight D. Eisenhower and his wartime Allies after failing to win a public U.S. apology for the intrusion into Soviet airspace. Pointing to the incident as evidence of Khrushchev’s leadership failure, Stalinist remnants in the Soviet Communist Party and China’s Mao Tse-tung were sharpening their knives against the Soviet leader in preparation for the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Having used just such gatherings himself to purge adversaries, all Khrushchev’s plans for 1961 were designed to head off a catastrophe at that meeting.

With all that as the backdrop, nothing threatened Khrushchev more than the deteriorating situation in divided Berlin. His critics complained that he was allowing the communist world’s most perilous wound to fester. East Berlin was hemorrhaging refugees to the West at an alarming rate. They were a self-selecting population of the country’s most motivated and capable industrialists, intellectuals, farmers, doctors, and teachers. Khrushchev was fond of calling Berlin the testicles of the West, a tender place where he could squeeze when he wanted to make the U.S. wince. However, a more accurate metaphor was that it had become his and the Soviet bloc’s Achilles’ heel, the place where communism lay most vulnerable.

Yet Khrushchev betrayed none of those concerns as he worked a New Year’s crowd that included cosmonauts, ballerinas, artists, apparatchiks, and ambassadors, all bathed in the light of the hall’s six massive bronze chandeliers and three thousand electric lamps. For them, an invitation to the Soviet leader’s party was itself confirmation of status. However, they buzzed with even greater than usual anticipation, for John F. Kennedy would take office in less than three weeks. They knew the Soviet leader’s traditional New Year’s toast would set the tone for U.S.–Soviet relations thereafter.