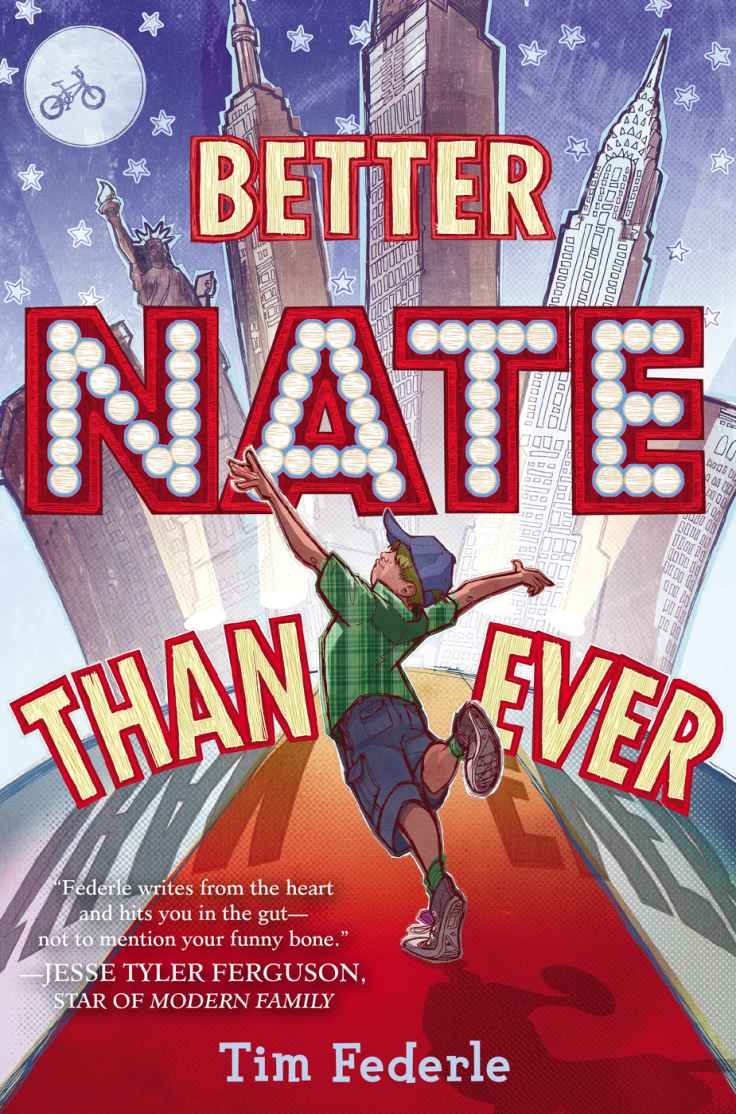

Better Nate Than Ever

Read Better Nate Than Ever Online

Authors: Tim Federle

This book is dedicated to you

A Quick but Notable Conversation with Mom, a Week Ago

This’ll Be Fast: You Might as Well Meet Dad, Too

Seventy-Seven Miles to Manhattan

One-Dollar Pizza/Priceless Stories for My Grandchildren

Definitely Changed, “For the Better” Undecided

Buying Clothes with an Aunt I Barely Know

Returning Home a Sopping Soldier in Tight New Clothes

Moving Ahead: I Know Several Portions of Hamlet

A Salsa Crawl Is Not a Dance Move

A Couch That Thinks It’s an Envelope

It’s Like a Bed but Stranger and Lumpier and with More Wooden Slats, and Hidden Crumbs

Lobbies Are Just Lobbies: A Weak Metaphor

First Time I Didn’t Like a Sweet

A Boy Soprano with a Ballsy Chest Voice

I

’d rather not start with any backstory.

I’m too busy for that right now: planning the escape, stealing my older brother’s fake ID (he’s lying about his height, by the way), and strategizing high-protein snacks for an overnight voyage to the single most dangerous city on earth.

So no backstory, not yet.

Just . . . fill in the pieces. For instance, if I neglect to tell you that I’m four foot eight, feel free to picture me a few inches taller. If I also neglect to tell you that all the other boys in my grade are five foot four, and that James Madison (his actual name) is five foot

nine

and doesn’t even have to mow the lawn for his allowance, you might as well just pretend I’m five foot nine too. Five foot nine with broad, slam-dunking hands and a girlfriend (in high school!) and a clear, unblemished face. Pretend I look like that, like James Madison.

I do, except exactly opposite plus a little worse.

By the way, despite our tremendous height gap, he and I weigh the same. The school nurse told me that once: “James Madison was just in, before you,” she said, grinning like her news was a Christmas puppy, “and you weigh the exact same!” This is the one attribute at which I’m

not

below average: body heft.

Oh, and I already knew that James Madison was in the nurse’s office before me that day, because we’d just passed in the door frame, and he licked the Ritalin crumbs from his lips and lunged at me to make me scream a little.

I screamed a little.

Luckily, I picked a good key and turned the shriek into a melody, walking into the nurse’s office humming a tune. Life hasn’t always been easy (my first word was “Mama,” and then “The other babies are teasing me”), but at least I’m singing my way through eighth grade, pretending my whole existence is underscored.

There. There’s your backstory. I was always singing.

Not that there’s any evidence. My parents weren’t very good about documenting my childhood; my older brother got all the video footage, including his first seven poops. By the time I was born, disturbing the tranquility of Anthony’s remarkable career as a three-year-old wonder-jock, the video cameras were fully trained on his every sprint, gasp, dive, and volley.

Those are sports terms. Reportedly.

So I always sang, not that there’s any proof of it. No high-res shots of little Nate Foster scurrying around the Christmas tree, belting “Santa Baby” in a clarion, silver soprano.

That’s just my imagination of my voice. Again: Nobody ever recorded it.

But I’m getting off track—you’re distracting me—and there is a lot to do.

“No pressure, but if you pull this off, you are going to be my hero forever.” This is Libby, my best friend for as long as I can remember (two years and three months, specifically, but I hate when stories are hampered by math). Libby’s standing in my backyard tonight, lit only by the moon. Although it might actually be the neighbor’s motion-activated floodlight.

“Bark! Bark!” That’s their dog. Yes, she’s definitely being lit by their floodlight.

“Libby, if I

don’t

pull this off and make it back home by tomorrow night, I’m dead. Like, my parents will never let me leave Western Pennsylvania again.”

I’m hugging my bookbag, which is stuffed with three pairs of underwear, one plastic water bottle (singers have to stay hydrated), deodorant (just in case I need it on the trip; so far I’m good, but I saw on the Internet that a teenager’s body can begin stinking at any moment), and fifty dollars. Fifty dollars should

be safe through at least Harrisburg, and once there, I’ll take my mom’s ATM card out and get some more cash.

Oh, yeah. I borrowed my mom’s ATM card. I’m babysitting it, we’ll say.

The plan is this: If I get money in

Harrisburg

, it’ll be less suspicious than visiting an ATM in our little town (unofficial motto: “48.5 miles from Pittsburgh and a thousand miles from fun”). When she gets her bank statement, Mom won’t suspect it’s me who stole from her; Harrisburg is the capital of Pennsylvania and thus must be crawling with big-city criminals.

“I’m serious, Lib. If anything goes wrong, my parents’ll never let me leave home again. Ever.”

“Luckily, they’ve never let you leave home

before

, either. So if you get permanently grounded for this, Nate, you won’t really know what you’re missing out on anyway.”

Unless I get trapped in New York without a hotel, in a freak late-October blizzard. Unless I finally make it back here after my trip and really

do

know what I’m missing out on, because I actually eat one of the famous New York street pretzels. Imagine: pretzels sold on the street! It’s as if anything is possible. Do they also sell hopes on the street? Do they sell hugs and dreams and height-boosting vitamins? Or hot dogs? I bet you they do.

Feather circles my feet in the grass, whining. I’m

sure he has to pee. Feather is so well trained (my older brother did the dog rearing; he’s not only the town sports star but a frickin’ dog whisperer, too, in addition to donating his old issues of

Men’s Health

to the library and also volunteer lifeguarding) that the dog only “goes” when we instruct him to. For a moment I want to believe Feather’s just sensing that I’m leaving. That he’s only whining because he’s scared. As scared as I am.

“

Go

, boy.” But really, he just has to pee.

Something stirs in the woods behind the house. Libby crouches down and her jeans strain at the knees. We have identical bodies, other than the obvious stuff.

“So we’re good on the alibi?” I say.

“Yes. We’re good. I’ll cover your dogsitting duties while Anthony goes off to win another track meet tomorrow. And if anyone calls your landline, I’ll pick up the phone and disguise my voice as yours.”

Libby’s being kind. We have the exact same voice already. When I order pizza, they always sign off by saying, “That’ll be thirty minutes,

ma’am

.”

“Let’s go over what happens if somebody tries to kidnap you,” Libby says.

“I make myself throw up.”

“That’s right.” She has theories for everything, and one of them is that if you throw up on criminals,

they’ll run. She watches more TV than I do.

“What if I can’t throw up? What if I haven’t had anything to eat?”

Libby smirks, reaching into her own bag and handing me a twenty-four-pack of Entenmann’s chocolate donuts. Nobody knows me like Libby.

“You’re so good to me,” I say. “Oh, God.” Now I’m hopping. “Maybe I should just stay home? This is crazy.”

“Don’t you think it would be crazier to stay here? And sell flowers the rest of your life?” The family legacy is a floral shop, Flora’s Floras. Mom runs it now, though we’re not making any real money. There’s nothing like a business in which your main product wilts by sundown.

“And tell me one more time,” I say, “what my New York catchphrase is? It’s—uh—

Gosh, that A train subway sure is running local again

. Right?”

Libby groans and takes me by the shoulders. “No, Nate. The key is to get it exactly right.

The A train is running local today, what a hassle

. That’s the phrase. I Googled ‘things that annoy New Yorkers,’ and I need you to trust me.” She twitches her nose, her habit when she’s nervous or certain I’m about to screw something up.

“The A train is running local today,” I say like a studious robot, “what a hassle.” I can handle this.

The neighbor’s floodlight clicks off, and for a moment it’s just me, Libby, Feather, and a sky of rural darkness, the crisp autumn air that leads to adventure. Or trouble. A bonfire that burns too hot, or a Halloween prank gone horribly wrong, or a boy-with-a-girl’s-figure getting murdered in New York City.

“Close your eyes,” Libby says. And when I do, and she

doesn’t

take my hand and put a treat into it—a lucky rabbit foot, once; tickets to a tour of

Les Misérables

another time—I sense something new is about to happen.

And just as I’m opening my eyes again, and watching her coming at me like

I’m

a chocolate donut, her mouth open and eyes closed and arms reaching out to me, my brother pulls his pickup truck into the side yard, high beams on full blast. Sixteen-year-olds always drive with their high beams on, to make up for their insecurity and lack of experience manning a seven-ton death toaster.

For the first time ever, Anthony has saved me from something.

“What are you freaks

doing

out here?” he says, slamming the truck door and turning his baseball hat around backward, rolling up a sleeve like he’s about to get into some dirty work.

“Keep your voice down, Anthony,” I say, “the neighbors are probably sleeping.”

“Oh please, Nathan,” he says, circling the entire length of his truck, inspecting it for the tiniest nick (this is a ritual). “Aren’t you usually belting out the chorus to

Gays and Dolls

or something around now?”

Try loving showtunes alongside an older brother who can bench-press your weight. No, literally! Before he became too embarrassed to be seen in public with me (right around when Libby dyed my hair blond), Anthony would bench-press me out back and we’d charge seventy cents to the neighborhood kids if they wanted to watch.

“It’s GUYS

and Dolls

,” I’m about to say, but don’t.

Libby moves away and looks at the stars, probably horrified that she was about to kiss me and got interrupted. Probably horrified that she was about to kiss me at all. “We’re hanging out here because there’s supposed to be a meteor shower tonight,” she says, lying to Anthony. I’m the only person she doesn’t lie to. “And your little brother and I never miss a show.”