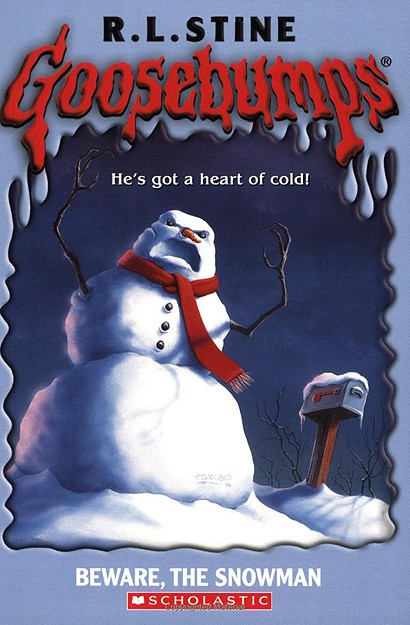

Beware, the Snowman

BEWARE, THE SNOWMAN

R.L. Stine

(An Undead Scan v1.5)

1

When the snows blow wild

And the day grows old,

Beware, the snowman, my child.

Beware, the snowman.

He brings the cold.

Why did that rhyme return to me?

It was a rhyme my mother used to whisper to me when I was a little girl. I

could almost hear Mom’s soft voice, a voice I haven’t heard since I was five….

Beware, the snowman.

He brings the cold.

Mom died when I was five, and I went to live with my aunt Greta. I’m twelve

now, and my aunt never read that rhyme to me.

So what made it run through my mind as Aunt Greta and I climbed out of the

van and gazed at our snow-covered new home?

“Jaclyn, you look troubled,” Aunt Greta said, placing a hand on the shoulder of my blue parka. “What are you thinking

about, dear?”

I shivered. Not from Aunt Greta’s touch, but from the chill of the steady

wind that blew down from the mountain. I stared at the flat-roofed cabin that

was to be our new home.

Beware, the snowman.

There is a second verse to that rhyme, I thought. Why can’t I remember it?

I wondered if we still had the old poetry book that Mom used to read to me

from.

“What a cozy little home,” Aunt Greta said. She still had her hand on my

shoulder.

I felt so sad, so terribly unhappy. But I forced a smile to my face. “Yes.

Cozy,” I murmured. Snow clung to the windowsills and filled the cracks between

the shingles. A mound of snow rested on the low, flat roof.

Aunt Greta’s normally pale cheeks were red from the cold. She isn’t very old,

but she has had white hair for as long as I can remember. She wears it long,

always tied behind her head in a single braid that falls nearly all the way down

her back.

She is tall and skinny. And kind of pretty, with a delicate round face and

big, sad dark eyes.

I don’t look at all like my aunt. I don’t know

who

I look like. I

don’t remember my mom that well. And I never knew my father. Aunt Greta told me

he disappeared soon after I was born.

I have wavy, dark brown hair and brown eyes. I am tall and athletic. I was

the star basketball player on the girls’ team at my school back in Chicago.

I like to talk a lot and dance and sing. Aunt Greta can go a whole day

without barely saying a word. I love her, but she’s so stern and silent….

Sometimes I wish she were easier to talk to.

I’m going to need someone to talk to, I thought sadly. We had left Chicago

only yesterday. But I already missed my friends.

How am I going to make friends in this tiny village on the edge of the Arctic

Circle? I wondered.

I helped my aunt pull bags from the van. My boots crunched over the hard

snow.

I gazed up at the snow-covered mountain. Snow, snow everywhere. I couldn’t

tell where the mountain ended and the clouds began.

The little square houses along the road didn’t look real to me. They looked

as if they were made of gingerbread.

As if I had stepped into some kind of fairy tale.

Except it wasn’t a fairy tale. It was my life.

My totally weird life.

I mean, why did we have to move from the United States to this tiny, frozen

mountain village?

Aunt Greta never really explained. “Time for a change,” she muttered. “Time

to move on.” It was so hard to get her to say more than a few words at a time.

I knew that she and Mom grew up in a village like this one. But why did we

have to move here now? Why did I have to leave my school and all of my friends?

Sherpia.

What kind of a name is Sherpia? Can you

imagine

moving from Chicago to

Sherpia

?

Lucky, huh?

No way.

It isn’t even a skiing town. The whole village is practically deserted! I

wondered if there was anyone here my age.

Aunt Greta kicked snow away from the front door of our new house. Then she

struggled to open the door. “The wood is warped,” she grunted. She lowered her

shoulder to the door—and pushed it open.

She’s thin, but she’s tough.

I started to carry the bags into the house. But something standing in the

snowy yard across the road caught my eye. Curious, I turned and stared at it.

I gasped as it came into focus.

What

is

that?

A snowman?

A snowman with a

scar

?

As I squinted across the road at it, the snowman started to move.

2

I blinked.

No. The snowman wasn’t moving.

Its red scarf was fluttering in the swirling breeze.

My boots crunched loudly as I stepped up to the snowman and examined it

carefully.

What a

weird

snowman. It had slender tree limbs for arms. One arm

poked out to the side. The other arm stood straight up, as if waving to me. Each

tree limb had three twig fingers poking out from it.

The snowman had two dark, round stones for eyes. A crooked carrot nose. And a

down-turned, sneering mouth of smaller pebbles.

Why did they make it so mean looking? I wondered.

I couldn’t take my eyes off the scar. It was long and deep, cut down the

right side of the snowman’s face.

“Weird,” I muttered out loud. My favorite word. Aunt Greta is always saying I need a bigger vocabulary.

But how else would you describe a nasty-looking, sneering snowman with a scar

on its face?

“Jaclyn—come help!” Aunt Greta’s call made me turn away from the snowman. I

hurried back across the road to my new house.

It took a long while to unpack the van. When we lugged the final carton into

the cabin, Aunt Greta found a pot. Then she made us hot chocolate on the little,

old-fashioned stove in the kitchen.

“Cozy,” she repeated. She smiled. But her dark eyes studied my face. I think

she was trying to see if I was unhappy.

“At least it’s warm in here,” she said, wrapping her bony fingers around the

white hot-chocolate mug. Her cheeks were still red from the cold.

I nodded sullenly. I wanted to cheer up. But I just couldn’t. I kept thinking

about my friends back home. I wondered if they were going to a Bulls game

tonight. My friends were all into basketball.

I won’t be playing much basketball here, I thought unhappily. Even if they

play basketball, there probably aren’t enough kids in the village for a team!

“You’ll be warm up there,” Aunt Greta said, cutting into my thoughts. She

pointed up to the low ceiling.

The house had only one bedroom. That was my aunt’s room. My room was the low

attic beneath the roof.

“I’m going to check it out,” I said, pushing back my chair. It scraped on the

hardwood floor.

The only way to reach my room was a metal ladder that stood against the wall.

I climbed the ladder, then pushed away the flat board in the ceiling and pulled

myself into the low attic.

It was

cozy,

all right. My aunt had picked the right word.

The ceiling was so low, I couldn’t stand up. Pale, white light streamed in

through the one small, round window at the far end of the room.

Crouching, I made my way to the window and peered out. Snow speckled the

windowpane. But I could see the road and the two rows of little houses curving

up the mountainside.

I didn’t see anyone out there. Not a soul.

I’ll bet they’ve all gone to Florida, I thought glumly.

It was midwinter break. The school here was closed. Aunt Greta and I had

passed it on our way through the village. A small, gray stone building, not much

bigger than a two-car garage.

How many kids will be in my class? I wondered. Three or four? Just me? And

will they all speak English?

I swallowed hard. And scolded myself for being so down.

Cheer up, Jaclyn, I thought. Sherpia is a beautiful little village. You might

meet some really neat kids here.

Ducking my head, I made my way back to the ladder. I’m going to cover the

ceiling with posters, I decided. That will brighten this attic a lot.

And maybe help cheer me up, too.

“Can I help unpack?” I asked Aunt Greta as I climbed down the ladder.

She pushed her long, white braid off her shoulder. “No. I want to work in the

kitchen first. Why don’t you take a walk or something? Do a little exploring.”

A few minutes later, I found myself outside, pulling the drawstrings of my

parka hood tight. I adjusted my fur-lined gloves and waited for my eyes to

adjust to the white glare of the snow.

Which way should I walk? I wondered.

I had already seen the school, the general store, a small church, and the

post office down the road. So I decided to head

up

the road, toward the

mountaintop.

The snow was hard and crusty. My boots hardly made a dent in it as I leaned

into the wind and started to walk. Tire tracks cut twin ruts down the middle of

the road. I decided to walk in one of them.

I passed a couple of houses about the same size as ours. They both appeared

dark and empty. A tall, stone house had a Jeep parked in the driveway.

I saw a kid’s sled in the front yard. An old-fashioned wooden sled. A

yellow-eyed, black cat stared out at me from the living-room window.

I waved a gloved hand at it. It didn’t move.

I still hadn’t seen any other humans.

The wind whistled and grew colder as I climbed. The road grew steeper as it

curved up. The houses were set farther apart.

The snow sparkled as clouds rolled away from the sun. It was suddenly so

beautiful! I turned and gazed down at the houses I had passed, little

gingerbread houses nestled in the snow.

It’s so pretty, I thought. Maybe I

will

get to like it here.

“Ohh!” I cried out as I felt icy fingers wrap themselves around my neck.

3

I spun around and pulled free of the frozen grip.

And stared at a grinning boy in a brown sheepskin jacket and a red-and-green

wool ski cap. “Did I scare you?” he asked. His grin grew wider.

Before I could answer, a girl about my age stepped out from behind a broad

evergreen bush. She wore a purple down coat and purple gloves.

“Don’t mind Eli,” she said, tossing her hair off her face. “He’s a total

creep.”

“Thanks for the compliment,” Eli grinned.

I decided they must be brother and sister. They both had round faces,

straight black hair, and bright, sky-blue eyes.

“You’re new,” Eli said, squinting at me.

“Eli thinks it’s funny to scare any new kids,” his sister told me, rolling

her eyes. “My little brother is a riot, isn’t he?”

“Being scared is about all there is to do in Sherpia,” Eli said. His grin

faded.

What a weird thing to say, I thought.

I introduced myself. “I’m Jaclyn DeForest,” I told them. Their names were

Rolonda and Eli Browning.

“We live there,” Eli said, pointing to the white house. “Where do you live?”

I pointed down the road. “Farther down,” I replied. I started to ask them

something—but stopped when I saw the snowman they were building.

It had one arm out and one arm up. It had a red scarf wrapped under its head.

And it had a deep scar cut down the right side of its face.

“That s-snowman—” I stammered. “It looks just like one I saw across the

street from me.”

Rolonda’s smile faded. Eli lowered his eyes to the snow. “Really?” he

muttered.

“Why did you make it like that?” I demanded. “It’s so strange looking. Why

did you put that scar on its face?”

They glanced at each other tensely.

They didn’t reply.

Finally, Rolonda shrugged. “I really don’t know,” she murmured. She blushed.

Was she lying? Why didn’t she want to answer me?

“Where are you walking?” Eli asked, tightening the snowman’s red scarf.

“Just walking,” I told him. “Do you guys want to come with me? I thought I’d walk up to the top of the mountain.”

“No!”

Eli gasped. His blue eyes widened in fear.

“You

can’t

!” Rolonda cried. “You

can’t

!”

4

“Excuse me?”

I gaped at them in shock. What was their

problem

?

“Why can’t I go up to the top?” I demanded.

The fear faded quickly from their faces. Rolonda tossed back her black hair.

Eli pretended to be busy with the red snowman scarf.

“You can’t go because it’s closed for repairs,” Eli finally replied.

“Ha ha. Remind me to laugh later,” Rolonda sneered.

“So what’s the real reason?” I demanded.

“Uh… well… we just never go up there,” Rolonda stammered, glancing at

her brother. She waited for Eli to add something. But he didn’t.