Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir (28 page)

Read Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir Online

Authors: Susie Bright

The dancers’ physical prowess was one thing — but the shocking thing about any stripper gathering, I discovered, was that you have never heard women talk so fast and so explicitly about money in all your life. They make the guys on the trading floor on Wall Street look like a bunch of pansies.

Debi was older than most of the others: twenty-seven. She was all about The Plan. “You can only buy so many pants,” she explained to me. “You’ll make more money dancing than you could ever spend on shoes and earrings. Your body is only good in this business for a few years. You have to think like you’re in the NFL. You gotta buy a house, buy investment property, buy stocks — or be like her” — she pointed at a platinum blond” — go to med school. Get straight A’s.”

“But if you fuck up and give it all to your lover” — her eyes shifted back and forth, like there were a few culprits in the room — “you might as well not have bothered!”

“What about her?” I asked, pointing toward a gorgeous girl, visibly tipsy, standing at the lasagna table. She’d had something more than pasta.

“That’s bullshit!” Debi’s afro, like Medusa’s, grew in size every time she tossed her head. “I’ll tell you one thing: That girl might piss it all away on coke, but everything she spent tonight getting loaded — she spent ten times that much on some loser who’s sucking her dry.”

“You mean a guy, her pimp?” I was such a tourist.

“No, her “boooyfriend,” Debi said, drawing out the word like a sick lollypop. “Or her butchie. Her fucking parasite. Same difference.”

Every woman in the room seemed to have a lover. Were they the ones she was talking about? The straight dancers were, come to find, members of that same Rajneesh commune I lived below on Valencia Street — they must be the ones paying the rent, not their orange-sashed boyfriends.

Some of the strippers were butches who worked in drag. They brought their femmes, other working girls. Who made more? I hadn’t figured that out yet.

I remembered Debi’s financial “seminar” many times as the years went by at

On Our Backs

. She was right; very few strippers took the fortune they made and protected their interests. The manager of the Lusty, Tamara — she sent her fiancé to law school. He insisted she stop stripping — and she was so proud he cared. Then she caught him racking up charges to whores on her credit card. He cracked her hard across the face when she confronted him. She swallowed a bottle of p

ills that night, and we sat around her deathbed at the UCSF emergency room until her parents flew in from Idaho to turn the machines off.

I thought they were going to kill us with a look. But we were her family, too. The lawyer “fiancé” was nowhere. Her mother and father thought sex work killed her, we whores. But betrayal killed her, and I don’t know when that started — it wasn’t on a brass pole.

“That’s the story,” Debi said. “The girls who wanna work one man — they put all their eggs in that basket. Or they want the perfect butch prince to save them. They give them all their money, they buy them a house, then the jealous prick insists they stop working. When our girl isn’t dancing anymore, the prince loses interest. He busts her flat, and she’s left with nothing.”

I floated around Goldie’s shower that day with such cheer. I remember everyone’s names, stage and real.

Debi was right about the short time many of them had left. Mary Gottschalk would die of breast cancer when she was thirty. Ramona Mast ate a Fentanyl patch, and her “lover” tried to make money off her suicide. Laurie Parker, the most talented lover in all of San Francisco, hanged herself when her girlfriend left her. Nicole Symanksi had her kids taken away, lost her teeth, froze to death on the street. Cindy Ricci disappeared back to Yosemite with nothing but a duffel bag on her back. She was a friend of mine. And another, and another. To paraphrase Dylan, “she was friend of mine.”

Those girls each made a million dollars in five years of work, and it did not save them.

“I don’t do that shit,” Debi said. “Don’t want a work wife who’s into that. I walk on the stage and I say, ‘We’re going to make a thousand dollars in the next forty minutes.’ And you turn over laps like pennies, until you hit the mark. I want a million wallets in one night; I don’t want one trick’s charity.”

Debi’s partner, Nan, was true blue. She had a “real” job, although it wasn’t glamorous in the least. She worked for the gas company, one of the few women at the time. Nan climbed up a fifty-foot telephone pole with only spurs & a butt strap to get that job.

She had taught physical education at the University of Minnesota, and when I told her about the Long Beach Women’s Studies Department, she had the best belly laugh. It was familiar. The other dancers looked at her — able-bodied, articulate, loyal — and sighed. Debi had someone for the long haul.

“We used to bomb adult book shops in Minneapolis, can you believe that?” Debi raised her cigarette like an imitation of a Molotov cocktail. “‘Violence against fucking women.’ The university’s whole Women’s Studies Department was in on it.” She smoothed out the apron around her waist. “That’s how Nan and I fell in love, back in the old separatist days. I was organizing a Take Back the Night rally in Minneapolis —”

“No, that was before.” Nan interrupted her with a wave of her champagne flute. “You were volunteering at the Harriet Tubman Shelter for Battered Women, and I was teaching street-fighting self-defense courses.”

Debi winked and took a sip. “It was love at first sight.”

“I can’t believe I didn’t already meet you at

Spinster Hollow,” I said, telling them about my insemination adventures.

“We all know where we’re coming from,” Debi said. “Now we’re going to make something erotic for women, the kind of sex we want,” she said. Her green eyes twinkled at you like a wish coming true. “Our little magazine is going to blow them away.”

Models Crying

Susie Bright:

Do you think lesbians have a different relationship to what their genitals look like than heterosexual women?

Photographer Tee Corinne:

I think they have a different impetus to learn.

L

ast summer, in 2010, I was at my friend Eddie’s Open Art Studio in Santa Cruz, eavesdropping on a patron who complimented his photographs’ sensitive approach.

“You don’t abuse the models, dear, do you?” she asked him. Ed somehow kept a straight face.

I couldn't resist. “Oh, my ex had a different philosophy,” I said, turning to her without introduction. “She was the staff photographer for

On Our Backs

. Honey Lee always claimed to be quoting Helmet Newton, but she’d say, ‘The shoot’s not over until the model cries.’”

Eddie shook his head at me — and put his arm around his fan. Yes, Ed, protect the audience — they don’t wanna know what we go through for this.

I’m glad I can make a joke about it now — I was often that very model, crying. I gave Honey Lee Cottrell, Tee Corinne, and every other photographer at our magazine, what they needed, no matter what the cost. They taught me everything I know about pictures.

The

On Our Backs

pictorials were the most visible, controversial part of our magazine. But the scandals arising from their debut were never on the mark. The critics who despised us said our photo shoots were sadomasochistic, which seemed to be code for other, unspoken faults.

Our photo shoots were masochistic, but not in the way they meant. I froze my ass off getting a shot many, many times.

The doubters asked whether one could look at a model and be aroused without knowing her résumé; “What if she was a racist?” What if she was a poor example of a human being?

These critics had never analyzed a single piece of art or advertising with this method before, but The Crucible atmosphere in the women’s movement of the eighties was contagious. It was like an upperclassman marching into you

r dorm room, drawing herself up to full height, and saying, “You should be ashamed of yourselves.”

Why did they make such a fuss? For real? My best answer today is that they were guilty, fearful, competitive, fascinated with power — but utterly thwarted in their own attempts to live large.

Our

On Our Backs

efforts had remarkable success. We distributed our zine all over the world. I still don’t know how we persevered. We were pushed down so many times, most forcefully by men with money, but most cruelly by other women, our peers.

Here was the real scandal of

On Our Backs

photography: We were women shooting other women — our names, faces, and bodies on the line — and we all brought our sexual agenda to the lens. Each pictorial was a memoir. That is quite the opposite of a fashion shoot at Vogue or

Playboy

, where the talent is a prop.

Most of our readers didn’t know that professional photography, particularly at that time, was an overwhelming male occupation — as macho as any steel mill, but without the affirmative action program.

The handful of women who worked as photojournalists were overwhelming lesbian — and closeted. Think how long Annie Leibowitz, the famed celebrity photographer, has been quiet about her life. When her lover Susan Sontag died, their relationship was not even mentioned in the Times obit. That is how mainstream lesbian photographers live, even to this day.

When we began our magazine, female fashion and portrait models — all of them — were shot the same way kittens and puppies are photographed for holiday calendars: in fetching poses, with no intentions of their own.

“Does this please you?” is the cachet of the entire pre-

On Our Backs

era of cheesecake and feminine glamour. Maybe the model is a “Betty,” or maybe she’s a “Veronica,” but the subject has no sexual motive of her own. Contrast a photograph of a Marlboro Man … he’s thinking as he smokes; his mind is ticking. Now consider Betty Grable looking over her shoulder at you … Am I cute?

That’s what the male centerfolds of female models were about: Am I pretty? Am I darling? What do you think? Do you want me? Could you want me? Rate me! Put me on a leash and walk me around the park!

The great relief of dyke porn was that all that went out the window. We had an objective on our minds; we didn’t need to be reassured that we were “hot.” We had a sexual story to tell. We asked each participant, “What’s yours?”

The first story was Honey Lee Cottrell’s. She and I met because she was the “heartbreak kid” who’d left Good Vibrations. I had inherited her job.

When she came back, we fell in love. I couldn’t wait to show her what

On Our Backs

proposed to do. Honey and her previous lover, Tee Corinne, had literally invented the erotic lesbian photographic scene of the seventies, entirely

underground. At every turn, their photos had been censored by the small lesbian publications they approached. It wasn’t Honey’s or Tee’s idea to shoot pomegranates and succulents as metaphors — they were simply thwarted with their nudes, left and right.

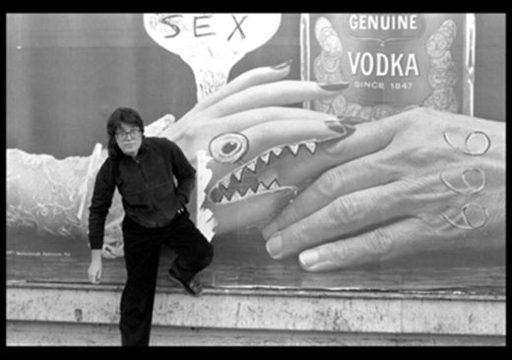

Honey Lee made an elaborate self-portrait for the first issue of

On Our Backs

, in the manner of a

Playboy

centerfold. It was called the Bulldagger of the Month.

In her portrait, Honey stands like a gunslinger in front of a window, a ghetto apartment, light pouring in. A white shirt is covering her breasts; her belly is rudely pushing over her the elastic of underwear. Her short hair stands straight up, like a brush; her eyes are like a raccoon’s, burning into the focal point. She’s got a Sherman burning in one hand. She looks like she could eat you with one bite.

On the Bulldagger Data Sheet across from her photo, we reproduced the iconic

Playboy

silly-girl questions about “Turn-ons” and “Turn-offs,” along with Honey’s accurate measurements and weight — numbers never whispered in a fashion magazine before.

The centerfold was Honey Lee’s secret valentine to me, because under “Turn-ons” she listed: “Tall, smart, talkative, pretty.” That was me, her blushing, chatty bride. Under “Turn-offs,” which made me howl, she listed, “Andrea Dworkin’s hair, oral sex, the refrigerator with rotten food in it.” So rude! Honey wanted to make a point that not all lesbians were cunnilingus fans. She said, “Everyone acts like it’s going to be like chocolate syrup, and it isn’t.” We argued, but I had to love her honesty. The slag on Andrea was bratty, but it was such a relief to be flip. We were so sick o

f the Queens of Saintly Feminism. They put their pants on one leg at a time- just like us, and they probably fucked just like us, too. The difference was a closet.

Similar to the

Playboy

design, we laid out three childhood photos of Honey Lee under the Bulldagger Questionnaire. I picked those out. They are still so poignant to me. The first one is of Honey Lee propped up on the kitchen table in her dungarees, reading Little Lulu comix from the Sunday paper and determinedly ignoring the fact that her mother is curling her hair. The way her little mouth is set — This is not happening to me. This is not happening to me — brings tears to my eyes. In the next photo, we see her with the curled hair, radiant on her bicycle, standing on a tree-lined street in

Jackson, Michigan. Her parents ran a boardinghouse there; her father was an over-the-road driver. She’s in a new dress, but I know the reason she’s thrilled is because of her shiny bike.