Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk (5 page)

Read Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk Online

Authors: Ben Fountain

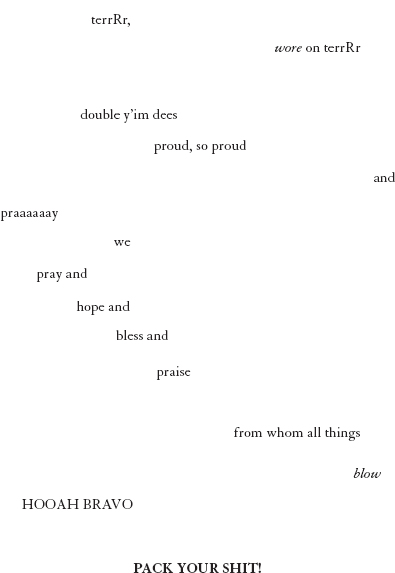

Americans fight the war daily in their strenuous inner lives. Billy knows because here at the contact point he feels the passion every day. Often it’s in their literal touch, a jolt arcing across as they shake hands, a zap of pent-up warrior heat. For so many of them, this is the Moment: His ordeal becomes theirs and vice versa, some sort of mystical transference takes place and it’s just too much for most of them, judging from the way they choke in the clutch. They stammer, gulp, brainfart, and babble, gum up all the things they want to say or never had the words to say them in the first place, so they default to old habits. They want autographs. They want cell phone snaps. They say thank you over and over and with growing fervor, they know they’re being good when they thank the troops and their eyes shimmer with love for themselves and this tangible proof of their goodness. One woman bursts into tears, so shattering is her gratitude. Another asks if we are winning, and Billy says we’re working hard. “You and your brother soldiers are preparing the way,” one man murmurs, and Billy knows better than to ask the way to what. The next man points to, almost touches, Billy’s Silver Star. “That’s some serious hardware you got,” he says gruffly, projecting a flinty, man-of-the-world affection. “Thanks,” Billy says, although that never seems quite the right response. “I read the article in

Time,

” the man continues, and now he does touch the medal, which seems nearly as lewd as if he’d reached down and stroked Billy’s balls. “Be proud,” the man tells him, “you earned this,” and Billy thinks without rancor,

How do you know?

Several days ago he was doing local TV and the blithering twit-savant of a TV newsperson just came out and asked: What was it like? Being shot at, shooting back. Killing people, almost getting killed yourself. Having friends and comrades die right before your eyes. Billy coughed up clots of nonsequential mumblings, but as he talked a second line dialed up in his head and a stranger started talking, whispering the truer words that Billy couldn’t speak.

It was raw. It was some fucked-up shit. It was the blood and breath of the world’s worst abortion, baby Jesus shat out in squishy little turds.

Billy did not seek the heroic deed, no. The deed came for him, and what he dreads like a cancer in his brain is that the deed will seek him out again. Just about the time he thinks he can’t be polite anymore the last of the well-wishers drift away, and Bravo takes their seats. Then Josh shows up and the first thing he says is, Where’s Major McLaurin?

Dime is casual. “Oh, he said something about needing to take his meds.”

“His meh—” Josh begins, but catches himself. “You guuuuyyyyyzzzzzz.” The very picture of young corporate America on the move, is Josh. He is tall, toned, handsome as a J.Crew model, with a nose straight and fine as a compass needle and a brilliant shock of glossy black hair, the sight of which triggers subliminal itchings in the Bravos’ peach-fuzz scalps. It has already been a matter of some debate as to whether Josh is gay, the consensus being no, he’s just your basic corporate pussy boy. “He’s whatcha call one a those metrosexuals,” Sykes said, whereupon everyone agreed that Sykes was gay just for knowing such a word.

“Well,” Josh says, “I guess he’ll turn up. You guys feel like getting some lunch?”

“We wanna meet the cheerleaders,” says Crack.

“Yeah,” says A-bort, “but we wanna eat too.”

“Okay, hang on.” Josh consults his walkie-talkie. The men exchange WTF looks. The vaunted Cowboys organization seems to be winging it with Bravo, the planning somewhere between half-assed and shit-poor. During a lull in the walkie-talkie confab Billy motions Josh closer, and the ever-alert Josh flexibly squats by his seat. “Advil,” Billy says, “were you able to find me any—”

“Oh

shit,

” Josh exclaims in a hot whisper, then “Sorry,” in his normal voice, “sorry sorry sorry, I’ll definitely get that for you.”

“Thanks.”

“Still hungover, dude?” Mango asks, and Billy just shakes his head. One night, eight men, and four strip clubs, all to no real purpose except that transactional blow job there at the end, thoughts of which make him want to shoot himself. Like a dental procedure it was, a blunt-force plumbing job, the memory of that girl’s head bobbing in his lap. Bad karma, for sure. Billy has overdrawn his karma account, that running tally of good and evil that Shroom described to him as the expression, the mental crystallization, as it were, of the great cosmic tilt toward ultimate justice. Billy scans the field but the punter is gone. His gaze sweeps the stadium’s upper reaches where the punts topped out, but it’s just air, he needs the concrete marker of the punts’ arc to get that vibe of Shroom hovering on the other side.

Shroom, Shroom, the Mighty Shroom of Doom who foretold his own death on the battlefield. When their deployment was done and he got his leave he was going on an ayahuasca trek to Peru, “going to see the Big Lizard,” as he put it, “unless the hajjis send me first.” Unless. Guess what. And on that day Shroom knew. Wasn’t that the meaning of their last handshake? Shroom turning in his seat just as they hit the shit, Mango already opening up on the .50 cal as Shroom reached back and took Billy’s hand. “I’m going down,” he yelled into the racket, which at the time Billy heard as

it’s,

“It’s going down,” his ear rounding off the weirdness so the words made sense. Later he’d cycle back to that moment and know it for what it was, the words and Shroom’s eyes with their hint of far remove, like he was looking up at Billy from the bottom of a well.

If Billy thinks about this for more than a couple of seconds a synthesized hum starts up in his head like a tremendous swell of organ music, not the sickly calf bleatings they played at Shroom’s funeral but a thunderous massing of mighty chords, the subsurface rumble of a tidal wave as it rolls unseen through the ocean depths. Spooky as all shit, not that he fights it; the big sound might be God banging around his head or some elaborately coded form of essential truth, or maybe both, or maybe they’re one and the same thing, so put

that

in your fucking movie, if you can.

Were you good friends?

asked the reporter from the

Ardmore Daily Star

. “Yes,” Billy said, “we were good friends.”

Do you think about him a lot?

“Yes,” Billy said, “I think about him a lot.” Like, every day. Every hour. No, every couple of minutes. About once every ten seconds, actually. No, it’s more like an imprint on his retina that’s always there, Shroom alive and alert, then dead, alive, dead, alive, dead, his face eternally flipping back and forth. He saw the beebs dragging Shroom into the high grass and thought Oh fuck or maybe just Fuck, that was the extent of Billy’s inner reflections as he scrambled off his belly and made his run. Weirdest thing, though, he retains this sense as he got to his feet of knowing exactly how it was going to turn out, the visualization so intense that it shook loose a kind of double consciousness that lingers to this day. His memory of the battle is mostly a hot red blur, but the premonitory memory is sharp and clear. He wonders if all soldiers who do these radical things get a brief sightline into a very specific future, this telescopic piercing of time and space that instills the motivation to do what they do. The ones who live, maybe. Maybe they all think they see, but the ones who don’t make it, they were wrong. Only the ones who survive are allowed to feel clairvoyant and canny, though it occurs to him now that Shroom, too, saw with equal clarity, just with the opposite result.

Hooah, Shroom. It feels like too many things to have to think about at once, movie deals and interviews and what it means to wear a medal plus that hard-core thing underneath it all, the primal and ultimately unfathomable facts of their engagement on the banks of the Al-Ansakar Canal. Your mind is not calm. You aren’t sick but you aren’t exactly well. There’s an airy sense of dangling or dangerous incompletion, as if your life has gotten ahead of itself and you need some time to let it back and fill. This feels right, this grasping of the time problem, here is the possible square one on which to build except Josh gives the word,

Lunch!,

and they rise. Little rockslides of applause tumble across the stands, and Sykes, the butthead, waves to the crowd like it’s all for him. Josh leads them bravely onto the stairs and it’s a long slow slog to the top, trudging upward in column like those poor doomed fucks near the end of

Titanic

striving against the horrible voids of sea and sky. If you relax even for a second, it will take you, thus a strategy is revealed: Don’t relax. Once they reach the concourse Billy feels better. Josh leads them up a spiral ramp where the wind shears into tight coiling eddies, tossing trash and dust around in little tantrums. A kind of coagulatory effect attends Bravo’s route as people stop, shout out, gape, or grin according to their politics and personality type, and Bravo blows through it all, polite and relentless, an implacable flying wedge of forward motion until the crew of a Spanish-language radio station grabs Mango for an interview, and all that good clean energy goes to hell. People gather. The air turns moist with desire. They want words. They want contact. They want pictures and autographs. Americans are incredibly polite as long as they get what they want. With his back to the railing Billy finds himself engaged by a prosperous-looking couple from Abilene who have their grown son and daughter-in-law in tow. The young people seem embarrassed by their elders’ enthusiasm, not that the old folks give a damn. “I couldn’t stop watching!” the woman exclaims to Billy. “It was just like nina leven, I couldn’t stop watching those planes crash into the towers, I just couldn’t, Bob had to drag me away.” Husband Bob, a tall, stooped gent with mild blue eyes, nods with the calm of a man who’s learned how much slack to give a live-wire wife. “Same with yall, when Fox News started showing that video I just sat right down and didn’t move for hours. I was just so proud, just so”—she flounders in the swamps of self-expression—“

proud,

” she repeats, “it was like, thank

God,

justice is finally being done.”

“It was like a movie,” chimes her daughter-in-law, getting into the spirit.

“It

was

. I had to keep telling myself

this is real,

these are

real

American soldiers fighting for our freedom, this is

not

a movie. Oh

God

I was just so happy that day, I was

relieved

more than anything, like we were finally paying them back for nina leven. Now”—she pauses for a much-needed breath—“which one are you?”

Billy politely introduces himself and leaves it at that, and the woman, as if sensing the delicacy of the question, doesn’t press. Instead, she and her daughter-in-law embark on a spoken-word duet of patriotic sentiments, they are 100 percent supporting of Bush the war the troops because defending szszszsz among nations szszszsz owl-kay-duzz szszszsz szszszsz szszszsz, the lady keeps leaning into Billy and tapping his arm, which induces a low-grade somatic trance, thus he’s feeling comfortably numb when the lid of his skull retracts and his brain floats free into the freezing air

No matter their age or station in life, Billy can’t help but regard his fellow Americans as children. They are bold and proud and certain in the way of clever children blessed with too much self-esteem, and no amount of lecturing will enlighten them as to the state of pure sin toward which war inclines. He pities them, scorns them, loves them, hates them, these children. These boys and girls. These toddlers, these infants. Americans are children who must go somewhere else to grow up, and sometimes die.

“Dude, that lady back there,” Crack says when they’re moving again, “the blonde with the little kids? When her husband was taking our picture she was totally grinding her ass up against my rod.”

“Bullshit.”

“No lie! Like instant wood, dude, she was shoving her ass right in there. Five more seconds and I woulda come, I shit you not.”

“He’s lying,” Mango says.

“Swear to God! Then I’m like, hey, give me your e-mail, let’s stay in touch while I’m back in Iraq, and it’s like she doesn’t know what I’m talking about. Bitch.”

Mango demurs, but Billy thinks it’s probably true—women will do some crazy shit around a uniform. He drops back a couple of paces and checks his cell. Pastor Rick has sent him another Bible text—